The First Time I Saw in Three Dimensions

What’s the Big Idea?

If the scientific consensus had been right, Sue Barry would still be seeing in 2-D. Barry was born with strabismus, a condition which prevented her eyes from gazing in the same place at the same time. By the age of two, she’d undergone three surgeries, but the operations succeeded only in making her eyes appear uncrossed — they still functioned separately. The whole world looked to Barry like a kid’s drawing.

She knew that a tree had branches, but she couldn’t see the layers of space between the branches. Watch the interview:

From birth until age 48, Barry used only monocular depth cues like shading and shadow to determine that some things were behind things or some things were rounder than other things. She believed everyone must see in 2-D, until she attended a college lecture on stereovision, the fusion of two slightly different images received by the right eye and left eye into one unified, dimensional world. “I remember leaving the classroom and thinking, what is [the professor] talking about?” she says.

At the time, the scientific consensus was clear: there was a critical window in early childhood during which you could build the neural connections required to utilize stereovision, and Barry had missed it. But the scientific consensus was wrong.

In her early forties, Barry’s vision began to deteriorate. Though her acuity was 20/20, she noticed that the faces of her children seemed blurry, and fluttering shapes would appear in the distance on the highway while she was driving. She made an appointment with a developmental optometrist, who finally informed her that her eyes were actually still working separately, as if they were crossed.

She could teach them to work together, the optometrist told her, by practicing the skills she’d missed out on as a baby–turning the eyes in to focus on a near object, or out to see an object in the distance. It was the first time Barry imagined it might be possible to change her vision.

It started small: after months of practice, the steering wheel of her car seemed to jut out into space in a parking lot. The arc of a faucet suddenly looked like a painting by Marcel Duchamp. She doubted her own eyes — after all, hadn’t she missed the critical developmental period? And yet her world had been palpably transformed: “It was only after I gained 3-D vision that I realized that tree canopies look round and that the outer branches enclose and capture whole volumes of space through which the inner branches permeate.”

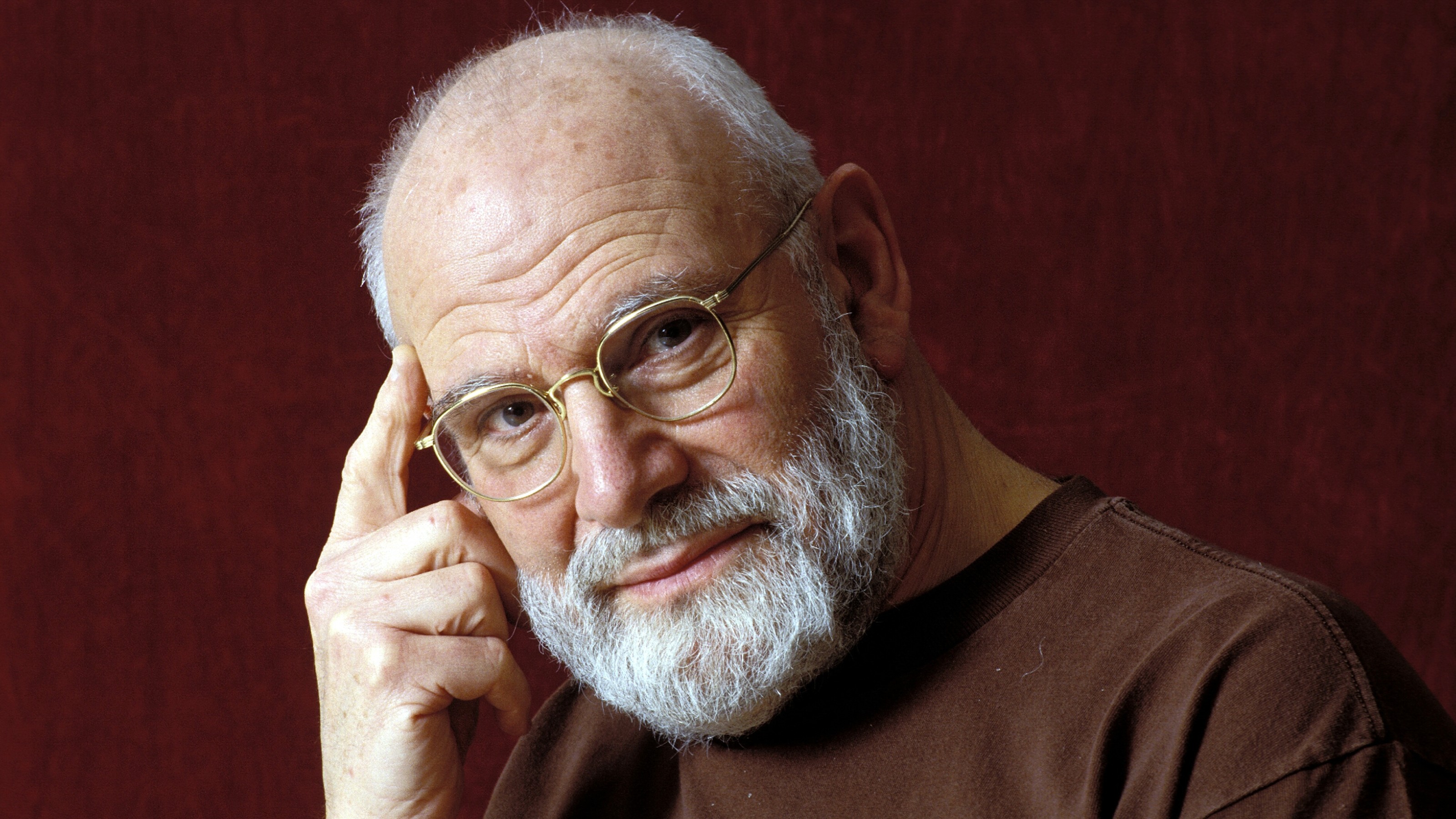

She waited three years to tell her doctors, family, and friends the news. Still unsure, she wrote a letter to the neurologist Oliver Sacks, who wrote back asking to meet her. Sacks confirmed through testing that she had in fact “rewired” her brain, upending the assumption that mental structure is fixed during childhood and inflexible forever after. (He dubbed her “Stereo Sue.”)

What’s the Significance?

Today, neurologists understand that the brain is an unbelievably plastic thing, capable of learning a new language or healing from injury well past adolescence. But Barry’s experience taught her a deeper, more essential lesson: every person possesses the ability to be a participant in her own rehabilitation. Patients are not merely subjects to be acted upon. Barry is confident that observation of your own habits and ailments can be a powerful tool in changing them — but only if you surround yourself with people who are willing to listen.

“Seek support from other people,” she advises. “If your doctor, if your therapist, if your friends are saying, ‘There’s no way you’re going to change,’ then guess what? There isn’t any way that you’re going to change. Seek [out only those] who are encouraging to you, not those who are going to try to decrease your enthusiasm.” She’s not advocating for a pseudo-scientific ignorance of facts, but she sees healing as a constant dialogue between doctor and patient, rather than something that is imposed. It’s a reminder that science is so often more about revision than certainty: the process of arriving at an understanding of exactly how much you don’t know, and all that you have yet to learn.

For more, check out Barry’s book, Fixing My Gaze.

Image courtesy of vlad_star/Shutterstock.