Could Designer Babies Close America’s Education Gap?

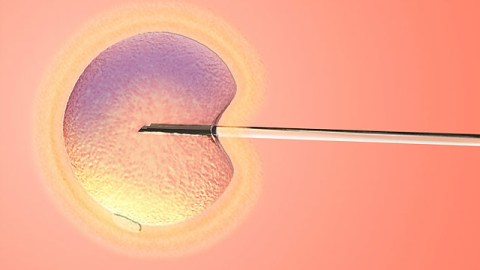

Advances in biotechnology have made the genetic enhancement of unborn children more and more feasible, raising exciting prospects along with thorny moral dilemmas. Does such enhancement represent a profound challenge to our common humanity, on par with the eugenics movement of the early 20th century? Or does it constitute important progress in a society that constantly seeks the best for its children?

Big Think experts have differed widely in their opinions. Last year, bioethicist Jacob Appel gave a surprisingly sanguine appraisal of “designer babies,” arguing that if the technology creates a slippery slope, we can find “level places on it.” He points out that the ability to pre-screen for certain conditions may actually tilt our moral obligation toward altering or discarding embryos. (If you knew that an embryo would be born with cystic fibrosis, could you bring it into the world in good conscience?)

But what about “adding extras”—such as math or musical talent—if and when that becomes possible? Appel is cheerfully unconcerned, arguing that “there isn’t that much difference between getting your child an SAT tutor and getting them into a good college, and making them a little bit more intelligent before they’re born. In some ways you can save money in SAT tutoring if you put the effort in early on.” As with genetic screening, Appel draws a close moral equivalence between the way we treat children before and after birth. The benefits we’d want to provide them in the world we should be able to provide in the womb; the same goes for the harms from which we’d want to shield them.

By contrast, Yale computer scientist David Gelernter views Appel’s future as a dystopic one. A noted thinker on the ethics of technology, Gelernter warns that rampant genetic engineering, if undertaken, will dehumanize us all. “By 2050…[if] you’re going to have a child, of course we’ll choose its sex and its appearance and stuff like that, but we can bump up his IQ by 10 points, or by really giving the very latest technology, you get 15 points more of IQ. So, your first kid is 15 points smarter than they would have been otherwise, but when you get around to having your second kid, the technology is better…So, [the] first kid is obsolete, essentially.”

As a threat to fundamental human dignity, Gelernter compares this scenario to the horrors—and attendant moral challenges—of World War II. Yet in a world where educational competition has never been more cutthroat, it’s easy to see how pre-birth intelligence-boosting could become a tempting option for some. Why wouldn’t the same parents who jockey to get their kids into the fanciest kindergartens seek out a genetic edge? What’s to stop the U.S. or China from seeking that same edge on a national scale? As the science of genetics races ahead, it remains to be seen where public opinion and policy settle on these issues—or whether they can settle at all on a slope some think is too dangerous even to contemplate.

More Resources

— Big Think Dangerous Idea #19: “Design Your Baby“