Why Does the Drug to Fight Opioid Addiction Cost $500 a Month?

The September issue of Harper’sfeatures juror excuses for why they were unfit to serve on the Martin Shkreli case. One called him the “most hated man in America,” for good reason: in 2015 his company, Turing Pharmaceuticals, raised the price of Daraprim by 5,000 percent. Over 200 potential jurors were excused. The responses were telling.

Shkreli didn’t help himself by being so outspokenly arrogant. While my favorite reply from the selection process is “he disrespected the Wu-Tang Clan,” his case points to something deeper in the human psyche: profiting from people’s sickness is gross. Shkreli is not the only one to have done it. Most prefer to fly under the radar.

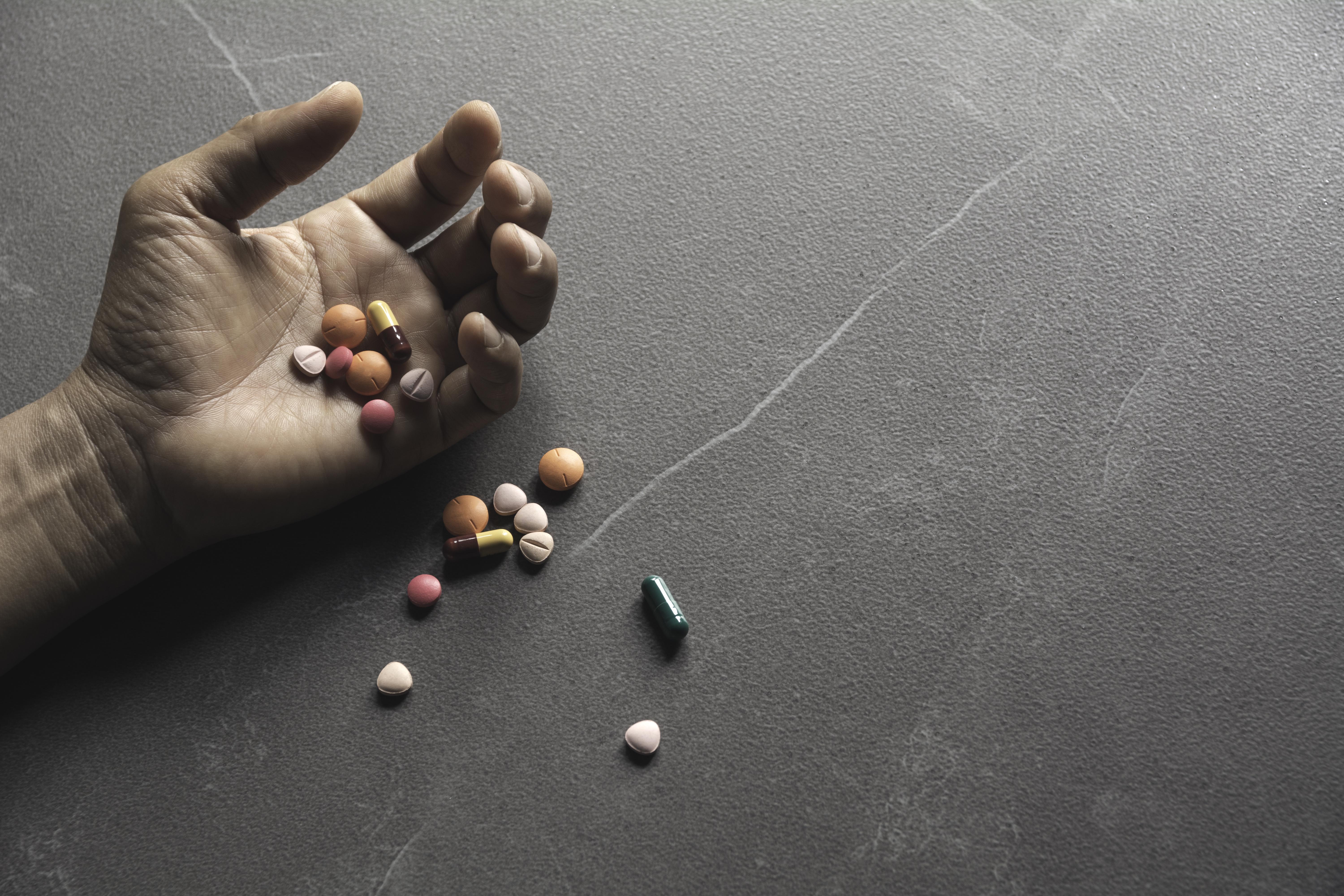

Take one of the nation’s greatest problems, opioid addiction. I’ve covered this often on this site, having had a family member and friends succumb to this addiction—thankfully, all have pulled through and recovered, at least for now. But addiction is insidious, and research on technology addiction has shown that everyone is vulnerable; there is no “addiction gene.” Regardless, we didn’t need the president to announce it as a national crisis, as it’s been the case for years.

In his book, The Power of Habit, journalist Charles Duhigg writes that addiction involves a three-step loop. First there’s a trigger informing your brain what habit to pursue. The following routine leads to the reward, which is how your brain remembers what routine to use when a cue is presented. So, trigger-routine-reward. He writes,

When a habit emerges, the brain stops fully participating in decision making. It stops working so hard, or diverts focus to other tasks. So unless you deliberately fight a habit—unless you find new routines—the pattern will unfold automatically.

This pattern explains opioid addiction: I don’t like the way I’m feeling. This pill makes me feel better. I feel better. Repeat. Duhigg argues that unless you find new routines to achieve a similar reward as offered by, in this case, opioids, you’re unlikely to break the chain of addiction.

There are other routes, however. One is Suboxone, a combination of buprenorphine and naloxone. An interesting and somewhat controversial method, as Suboxone can also be addictive: buprenorphine is an opioid while naloxone blocks the pain relief and other effects of opioids. There is evidence that Suboxone could get you high, though probably not as much as, say, heroin. Many side effects exist, though for some the drug works like a nicotine patch: lower dosages until you free yourself from the grip of addiction.

There’s a larger issue, however: cost. While the patent on Suboxone expired a while ago, the price remains prohibitive. As University of California professor Robin Feldman writes,

Oral film strips now cost over US$500 for a 30-day supply; even simple tablets cost a whopping $600 for a 30-day supply.

How is this possible for a generic? Patents offer corporations an opportunity to recoup money spent on research for their products. You have twenty years to earn your money back, plus, if you’re smart about it, some on top. But pharmaceutical companies delay expiration through a variety of means: slight changes in the medicine’s dosage or formulation; refusing to sell generics to other companies; petitions for further research that are merely stalling tactics. If you’ve got a blockbuster, you don’t want to lose out.

Few industries have exploited the concept of free market capitalism like pharmaceutics. As Feldman reports, 80 percent of profit growth in 2015 for the top twenty companies were from price hikes. And America is their favorite target audience. As she reports,

The liver failure drug Syprine, for example, sells for less than $400 a year in many countries; in the U.S., the average list price is US$300,000. Gilead’s hepatitis C drug, Sovaldi, reportedly sells for the equivalent of $1,000 abroad – in the U.S., it sells for $84,000.

One contentious paragraph in a minor study from 1980 kicked off the opioid epidemic. The graph claimed opioids were not addictive. Our understanding of addiction has changed much, but unfortunately opioids remain highly profitable for doctors and corporations. As long as they earn a profit on both ends—relieving pain then slowing the ensuing addiction—they’ll want to maximize their bottom end.

Sadly, for us, the bottom is where too many end up. While the black market and pill-happy doctors continue to prescribe a feasible route to addiction recovery remains inaccessible thanks to expense and blocked access to generic companies. The epidemic is showing no signs of slowing, and the industries that are supposed to be helping are doing everything but.

—

Derek is the author of Whole Motion: Training Your Brain and Body For Optimal Health. Based in Los Angeles he is working on a new book about spiritual consumerism. Stay in touch on Facebook and Twitter.