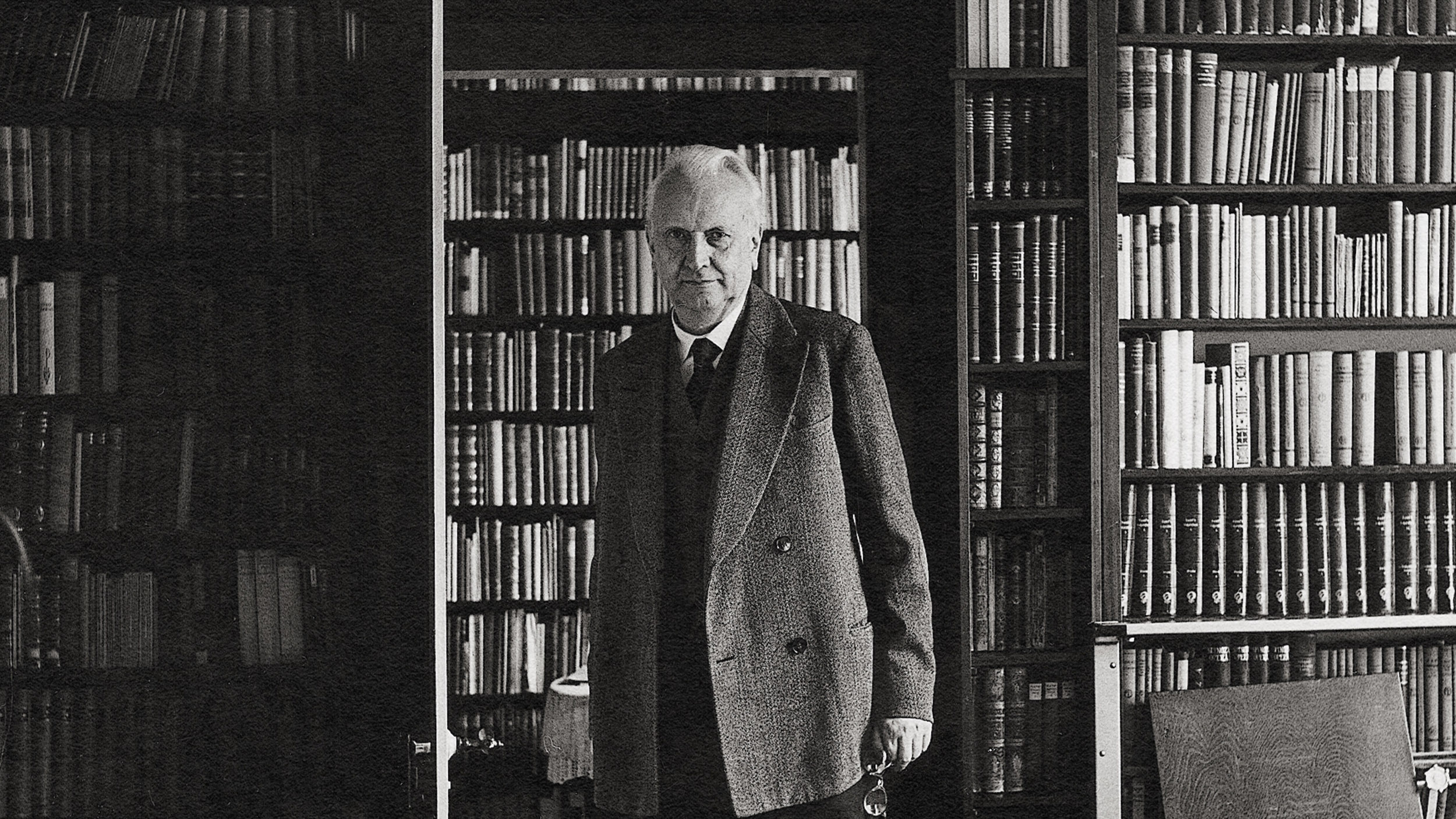

The novelist explains why was inspired to get inside the head of someone suffering from the brain disorder.

Question: Why were you inspired to write about someone suffering from dementia in Ptolemy Grey?

Walter Mosley: My mother, for many years, has been very slowly going into a state of dementia. It could be 15 years, since my father died. And, you know, it got worse and worse over the years. In the beginning I didn’t quite realize it and then it seemed more quirky than it seemed like some really somatic issue. And finally, in the last few years, four or five years of her life, it was obvious that she was suffering from dementia, a certain kind of dementia. And I had to, you know, because my mother was an only child, my father was an only child, I’m an only child. Because there’s really no family, I had to really kind of step in and try to take care of her.

And in taking care of her, I had to pay a lot of attention, I really wanted to be very clear, like a lot of people come to me and say, “Well, you should do this to her. You should make her do this. You should do this.” And I said, “Look, this is a woman who used to change my diapers. This is the person who took care of me more than I will ever take care of her. So I can’t do that. I have to respect her even if she’s having problems.” And so one of the issues was to figure out how she communicated and how I can communicate with her and how we could come to decisions together even though she was losing her ability to do that. And in the middle of doing that, I decided to write this book.

Question: What did you learn about dementia from taking care of your mother?

Walter Mosley: My experience of people in dementia is that a lot of their personality, a lot of their knowledge, a lot of their experience is still there but there’s not a direction connection that they can just reach out and get it and then bring it back. There’s a word, they know there’s a word, but they don’t remember what that is. There’s a word that describes something. There’s a thing that they have to do, there’s something that’s very important. It’s almost there within the range of their mind and they have to sit there and go through a really convoluted process of thought and memory to try to retain that—to regain it. And sometimes they can and sometimes they can’t.

As time goes on, they can less and less. Everything is still there. The person is still there, but they’re not as connected as they once were. And that’s what I was trying to talk about. That was my experience with my mother, but with a lot of other people, you know, as they get older as memories fade, as these doors start to close on parts of there lives for who knows, maybe physical and somatic reasons, maybe they’re emotional reasons.

Recorded November 10, 2010

Interviewed by Andrew Dermont

Directed / Produced by Jonathan Fowler