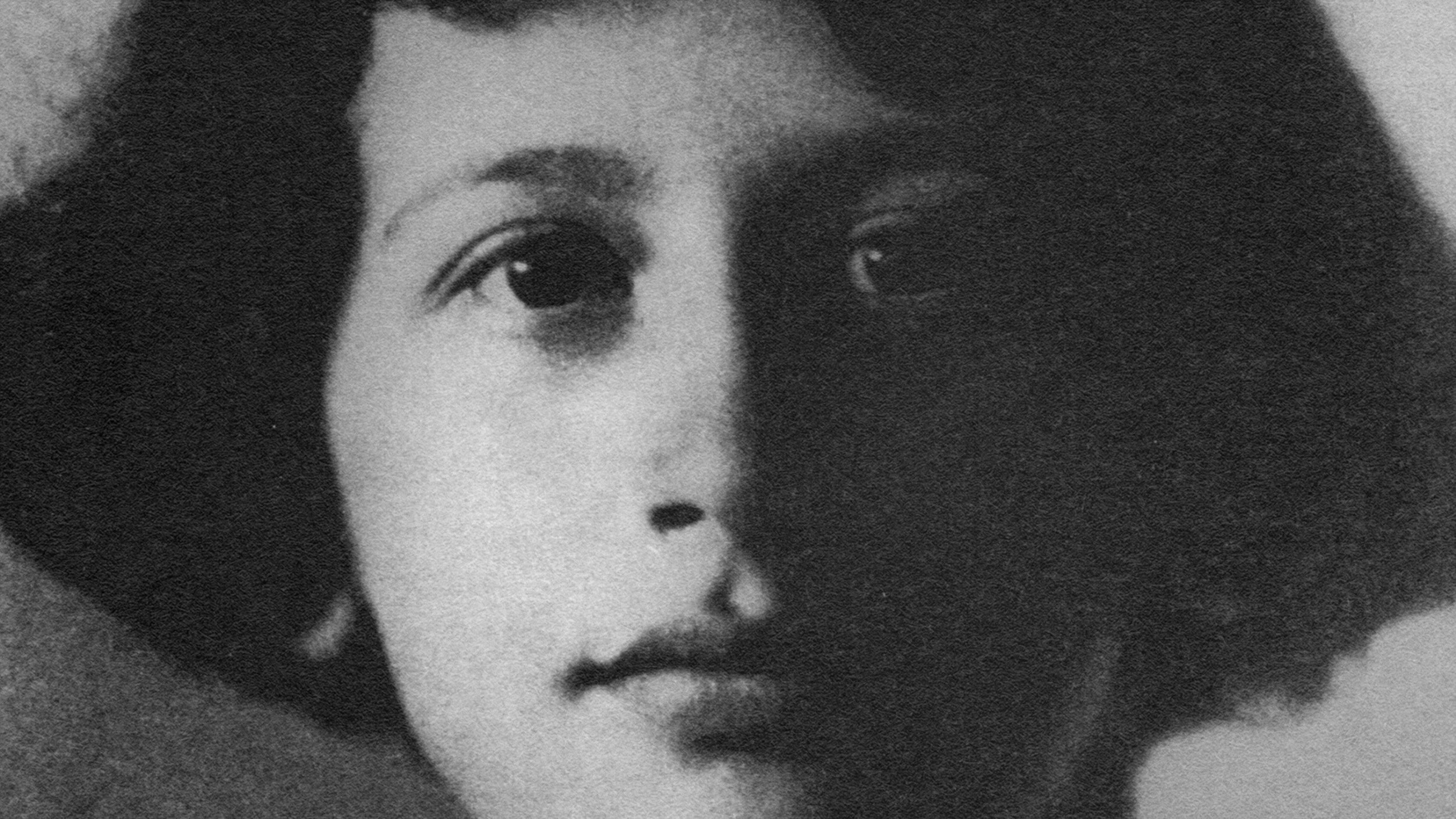

Nasr as born and raised in Iran, and lived and studied in England and America.

Vali Nasr: I was born in Iran. I lived in Iran until I was 15, 16 years old before I went to school in England. And then the Iranian Revolution happened in 1979. My family left Iran, and I with them.

We settled in the United States in Boston. It was right about the time that I started my undergraduate studies at Tufts University. So the events of 1979 in Iran – the revolution; the explosion of Islamic politics in the Middle East at the time; the questions that Americans had about what happened in Iran; what was happening in the Middle East; why Islam had all of a sudden become so important – were very formative. Because in many ways I was impacted by that revolution immensely, and I was in American universities at a time when these questions were becoming increasingly more important.

Well my impressions were not so much shaped by my experiences in Iran, but rather experiences in England, because I went to school in England.

My school was like Harry Potter’s school. It was a boarding school with all those kinds of structures that are associated with English boarding schools. And I compare it constantly – the culture of teenagers, and youth, and academia, and what I knew of England – with America. And for me, the adjustment was not so much as a Middle Easterner coming to America, but as somebody who had gone to high school in England coming to America.

While we were in Iran, I always thought I might have a future in public life.

My father was an academic. He was also involved in public life in Iran.

But also once in America I gravitated much more towards an intellectual career. I knew from undergraduate years at Tufts that I wanted to be an academic. Intellectual questions, the idea of the Middle East, theoretical debates within comparative politics, history--they always fascinated me.

And also when you go to school in Boston, it’s very easy to lose sight of the real world, and to only think of a career that is focused on intellectual questions. And because I came also from a family of academics, it almost was much more natural for me to go down that road.

Recorded on: Dec 3, 2007