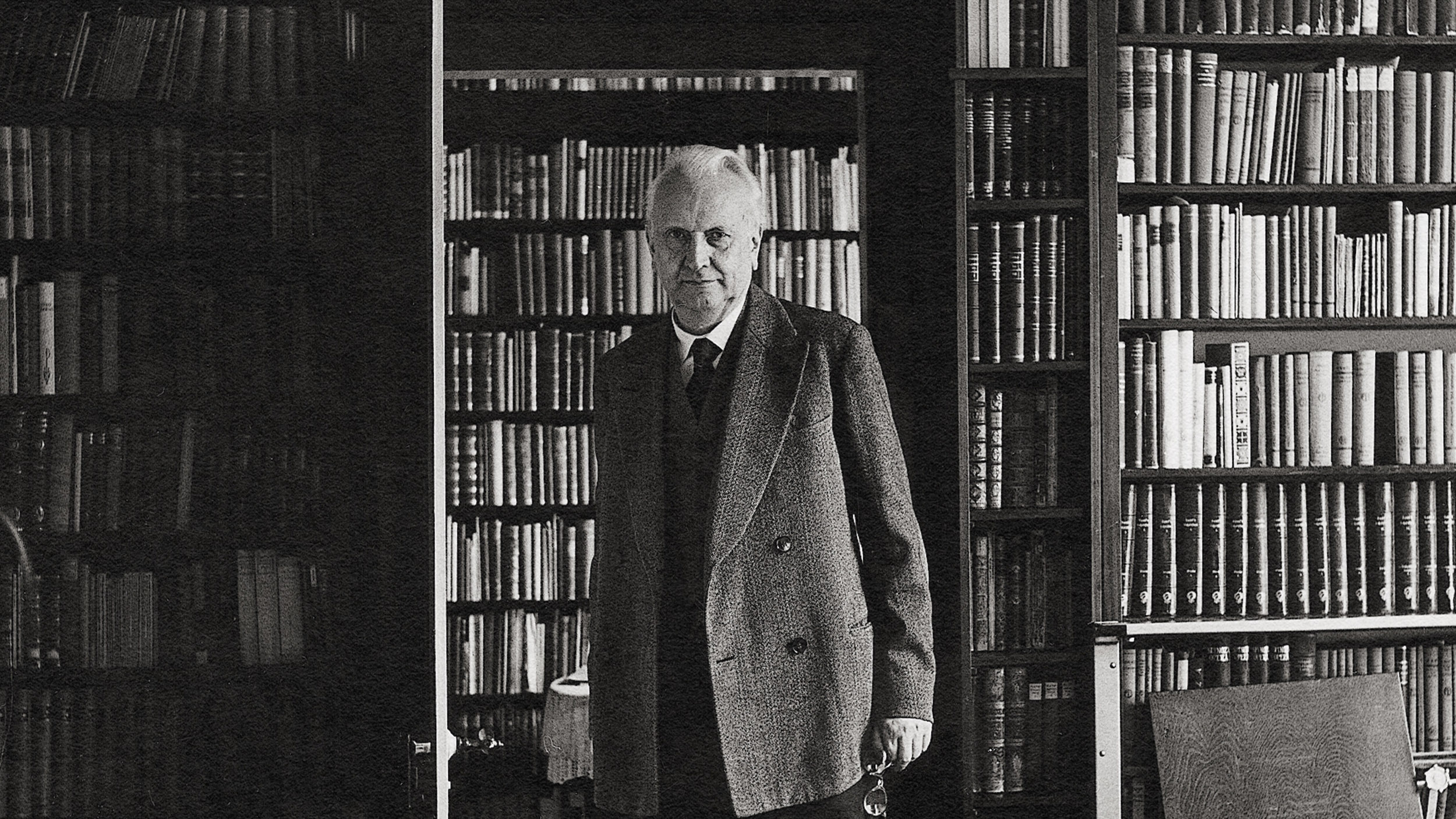

Do some of the essential findings of modern science rule out the possibility of free will? Is there a separation between mental and physical entities? Does it matter? The philosopher outlines a sometimes “silly” and “embarrassing” debate.

Question: Does quantum mechanics speak at all to consciousness?

David Albert: Well, it's been thought to, and presumably it does in one way or another. There have certainly been episodes in the history of struggling with the measurement problem over the past 50 years or so when distinguished physicists -- for example, Eugene Wigner, Nobel prize winner, enormously distinguished theoretical physicist of the first half and middle of the 20th century -- became convinced around the middle of the century that consciousness was going to be an absolutely essential and ineliminable ingredient of any possible solution to the measurement problem that we were talking about before. You remember that the problem was that when we rip this box open we see an electron either here or there, but the fundamental quantum mechanical equations of motion, if you apply them as well to our brains, would seem to predict the opposite, okay, that we don't distinctly see an electron here or there; rather, our brains end up in a superposition of the state associated with seeing it here and the state associated with seeing it there. That is, our brains end up in some condition where it fails even to make sense where we believe the electron to be. Okay.

Wigner took a look at this situation and said, well, so apparently what's going on here is that our brain, or at the very least our mind, seems to be evolving in a way that directly violates these fundamental equations of motion. And Wigner's approach to this was, instead of seeing this as bad news, okay, to see it as the news we've been waiting for, you know, since the beginning of science. Here is finally a proof that the mind of the observer is not a physical object and is not tied to physical objects in the way that rocks are or tables are or chairs are, so on and so forth. That is, the reason that the fundamental equations applied to our brains end up making the wrong predictions -- so said Wigner -- was because our brains have this special additional feature of being associated with consciousness, okay?

And this had the sort of cute effect of turning the traditional mind/body problem on its head. Traditionally the worry has been that the picture of the world that's emerging from physics is hostile to mind, that there's no place for mind in it, that we can analyze everything in terms of the physics of our brains -- why I'm saying this, why I do everything I do, so on and so forth -- it's hostile to mind, it's hostile to all of these things that we associate with mind, like freedom of will, so on and so forth. Wigner thought he had an argument that as a matter of fact in quantum mechanics, precisely the opposite turns out to be true: not only is physics not hostile to the idea that there is a distinct nonphysical, mental thing intervening in the physical world; not only is it not hostile to that; it absolutely needs that in order to make the right predictions. It absolutely needs this mind to come in and violate the equations of motion in order to make this electron end up in one determine place or another, which is what we observe it doing. So Wigner thought first of all he had for the first time a clean mathematical definition of the difference between a physical entity and a mental entity. A physical entity is by definition an entity that obeys these equations of motion. A mental entity is the kind of entity that is capable of causing violations of those equations of motion. Good.

This sounds cute for about 10 minutes, but it quickly became embarrassing. I remember myself as a young graduate student being at conferences where Wigner would stand up and speculate that although dogs could likely cause violations of the equations of motion, mice probably couldn't. And it just became silly and embarrassing, and one didn't know where he was coming up with this, and one was going to be forced, in order to write down the fundamental physical laws in a clean way, to make these distinctions between conscious and not conscious; whereas what seems much more plausible to everybody is that there's some continuum going from conscious to not conscious, rather than some clean cutoff point. And it was just a mess. So this was a view that was entertained seriously for about a 15-year period from the early '50s, maybe, to the late '60s and hasn't been taken particularly seriously by physicists since then. On the other hand, the existence of this view in this earlier historical period has been a goldmine for New Age enthusiasms about quantum mechanics ever since then.