As sequencing individuals’ genomes becomes cheaper and easier, how can we prevent the release of private genetic information onto the Web?

Question: What kinds of bioethical issues arise in your work, and how do you address them?

rnGregory Hannon: In our own work, I think we encounter bioethical issues in a few different ways. One is anytime we are dealing with experiments with living animals. There are certain standards that we have to maintain about the treatment of those animals. And we also try to plan using statistical tests to make sure that we use enough animals to get a definitive answer, but no more than we actually need to do an experiment.

rnFrom the standpoint of using human materials, we encounter issues of bioethics in two different ways. They are in some ways related and I think this goes to the development of a lot of these new high-capacity technologies that are being deployed in biology at the moment. So, on one hand, anytime we use human’s samples, there are a set of rules that are in place to maintain the anonymity of patients. And so, for example, when tumor samples are collected, they are anonymized and we have no way of tracing back the material that we are analyzing to the patient that was its source.

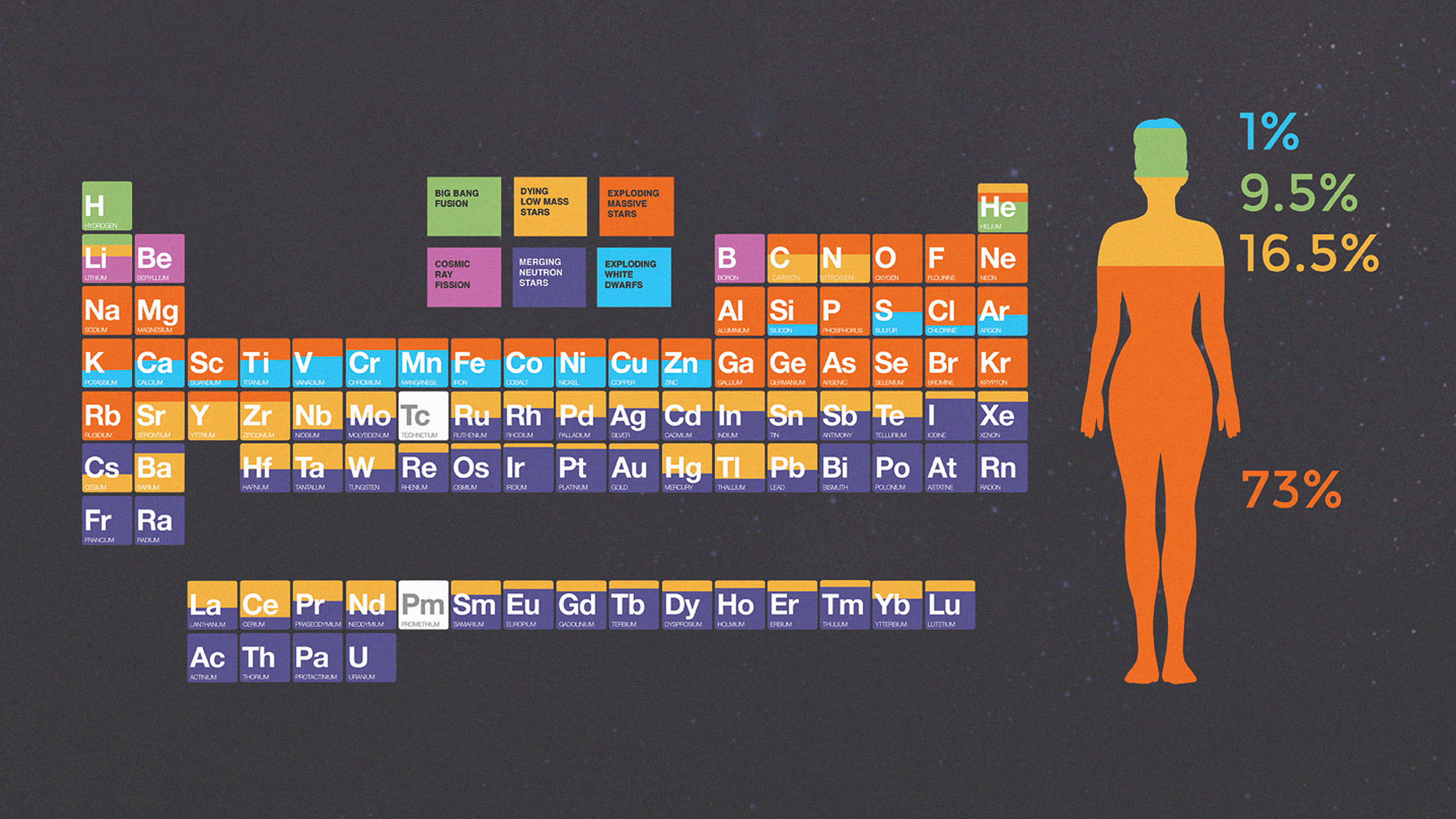

rnThe difficulty comes as we are more and more able to sequence people’s complete genomes for reasonable cost and in a very short time. If you think about how long the human genome project took and what its cost, I mean it was astronomical, compared to today when we could conceivably sequence an entire human genome in probably a week, maybe two weeks and presently for a cost of $40,000 to $50,000. And that time it’s taking to resequence a genome and the cost of doing so is dropping continuously to the point where, really by the end of this year, it will be down to $10,000 and maybe one week. And who knows where we will be in another year or so.

rnEssentially, once you have determined that genomic sequence, there is a unique identifier, an identifier unique to that person in whom the sample was derived. Now, if we go to publish data derived from that sequence, we are obligated to put the primary – the raw data to make it available to the community. So that means that a sample has turned into a sequence which is unique to that individual, which then essentially, in some ways, public. Now for other investigators to access that, they need to have specific bioethics training, etc., but that information is out there. And although it’s not immediately connected to that person from which that sample is derived, it is in some ways eventually connectable.

rnAnd so I think that one of the places that we really struggle now is using the power of these new sequencing tools to try to understand biology and how we can do that in a way that doesn’t necessarily put the sequence of many people’s genomes essentially freely accessible on the Web. And I think this is something that a lot of people are struggling with at the moment as the sequencing technologies that I’ve mentioned become more and more widely available within the academic community. We need to establish ways to, I think at least, anonymize the information that we provide to the community without degrading the quality of the science that we do and without hampering the ability of others to analyze that data and reproduce our work, or at least verify our conclusions.

rnQuestion: Are you optimistic that patients’ genetic information can be successfully anonymized?

rnGregory Hannon: I think it will happen. A lot of it is driven – there is a sort of tug of war between maximizing people’s access to your raw information because essentially you’ve spent the money, you’ve spent the time, you’ve produced this resource, you’ve analyzed it in one way. But it could probably be analyzed in an infinite variety of ways by others. And so, you want to have people maximally be able to make use of the data you generate. And also able to, as I said, verify your conclusions. On the other hand, there is this drive to maintain privacy and in the end, what’s going to have to happen is that the community will have to establish a set of procedures that are universally acceptable to allow a sequence to remain private and anonymous without destroying the value of the data that we publish. And scientists can take a lead in this, scientific journals can take the lead in this, but it is something that we are going to face remarkably soon.

Recorded on February 9, 2010