Hudis says mapping the human genome was the most exciting effort of the past decade.

Question: How has mapping the human genome influenced your field?

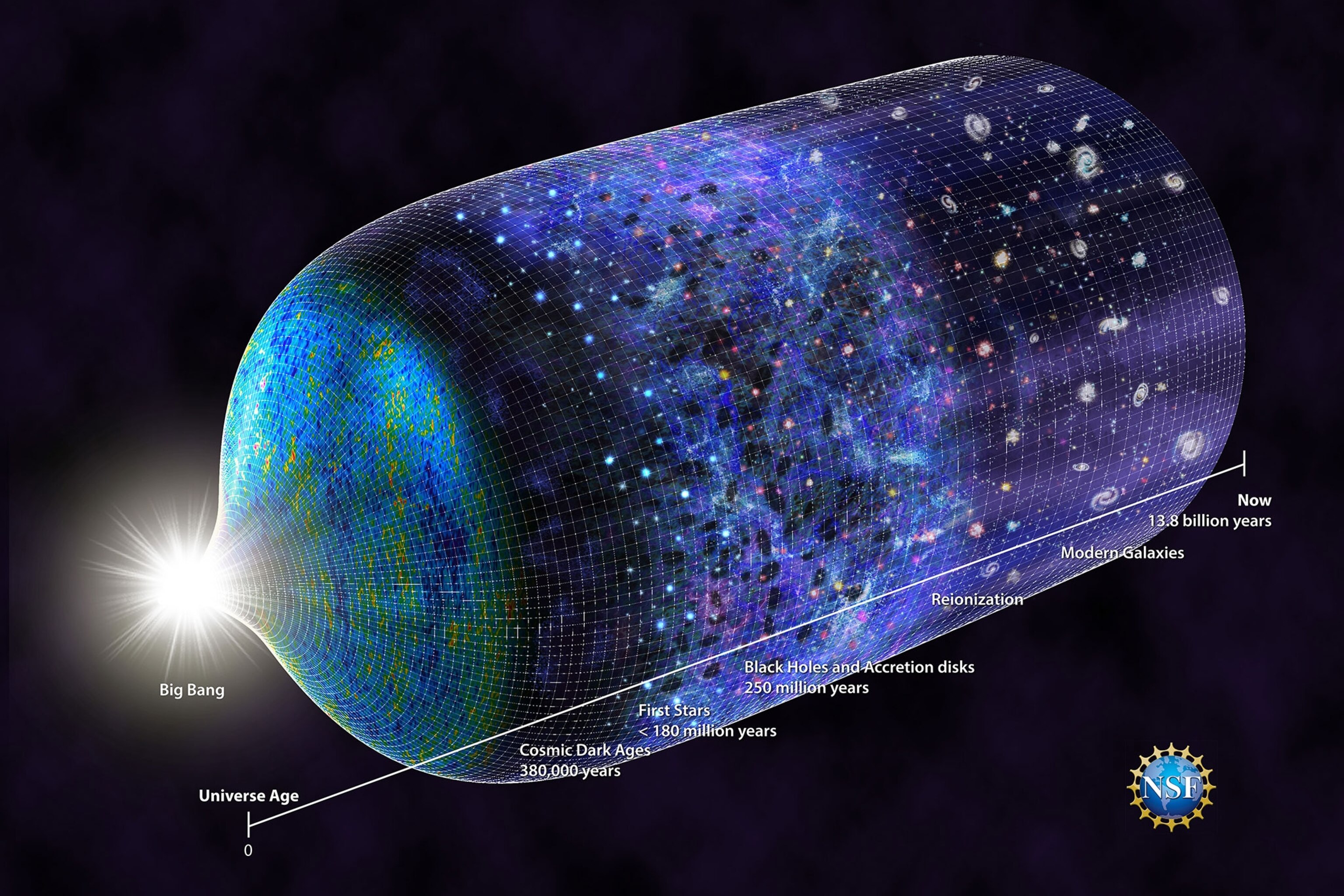

Clifford Hudis: So the mapping of the human genome was really the exciting effort of the past decade approximately and we were really excited that by doing this we would open up very specific directions for research, and I think like all good science it has led us to new frontiers but maybe not the ones that we’ve expected. The mapping of the human genome has not yet yielded a narrow “ah-ha” moment: This is the cause of breast cancer specifically or cancers in general. It has, however, taught us amazing things, amazing, about the heterogeneity, that is to say the variations, within the genome for people, that’s me to you, and even within people and even narrowly within tumors. So that has raised the level of complexity for us. It’s better to know that but I guess the short answer is no, the mapping of the genome has not yet yielded for us clinically relevant breakthroughs.

Question: What is the world’s biggest medical challenge?

Clifford Hudis: Well, that’s a really great question for an oncologist in a developed country because again the world’s biggest health challenge is probably pediatric illnesses like infectious diarrhea, malaria, and communicable diseases, and so if you wanted to ask me that same question in another way, “What is the biggest bang for the buck you get with your health care dollar?”, it’s investing in clean water, malaria nets and childhood immunizations around the developing world.

Card: How has science changed humanity?

Clifford Hudis: Yeah. Well, there was a lovely piece in the New York Times either Saturday or Sunday of this past week in the op ed that was written by an author reflecting on initially a request for one of his books from a soldier in Iraq or at least he was writing about this, but it was more broadly a plea for incorporation of science into everyday life and appreciation for it. And it’s a very funny paradoxical moment we have right now. We’ve never been more high tech. We rely on things like video cameras, cell phones, spinning platters of information, hard drives, and we’re willing to essentially not even learn how they work or even care. We want to see them almost as magical and they’re really not. They are all built by very carefully pursued scientific or upon scientifically-- scientific principles that are- have been carefully studied, and the reason I’m emphasizing that area is this. I think that we need to value science far more broadly in our population, in our education systems, than we heretofore have, and I think we have to have an appreciation for science and scientific method across society and across domains whether it’s communications, media, education, economics even or my narrow area of biological sciences. There is no advance that I take advantage treating my patients right now that isn’t born of the scientific method.

Question: What is the most exciting new technology you are working with?

Clifford Hudis: I think the most exciting technology remains actually the same technology that we were talking about when we discussed the mapping of the human genome. Our ability to drill down on and essentially dissect base pair by base pair the code of life, the DNA in our chromosomes, I think ultimately holds the key to everything, and if it doesn’t hold it in a very narrow, specific sense it holds it because it is events that are related to that code that matter. It is the what we call epigenetic events that we only now know about because of our ability to study the genome. I think that fundamentally this is the key to unlocking cancer and many other diseases.