Before setting off on a new novel, the author must be fully equipped with a sense of his characters, must have a path in mind, and must be able to see an ending in the distance, like a clouded mountaintop.

Question: Do you have the whole plot arc sketched out before you begin a novel?

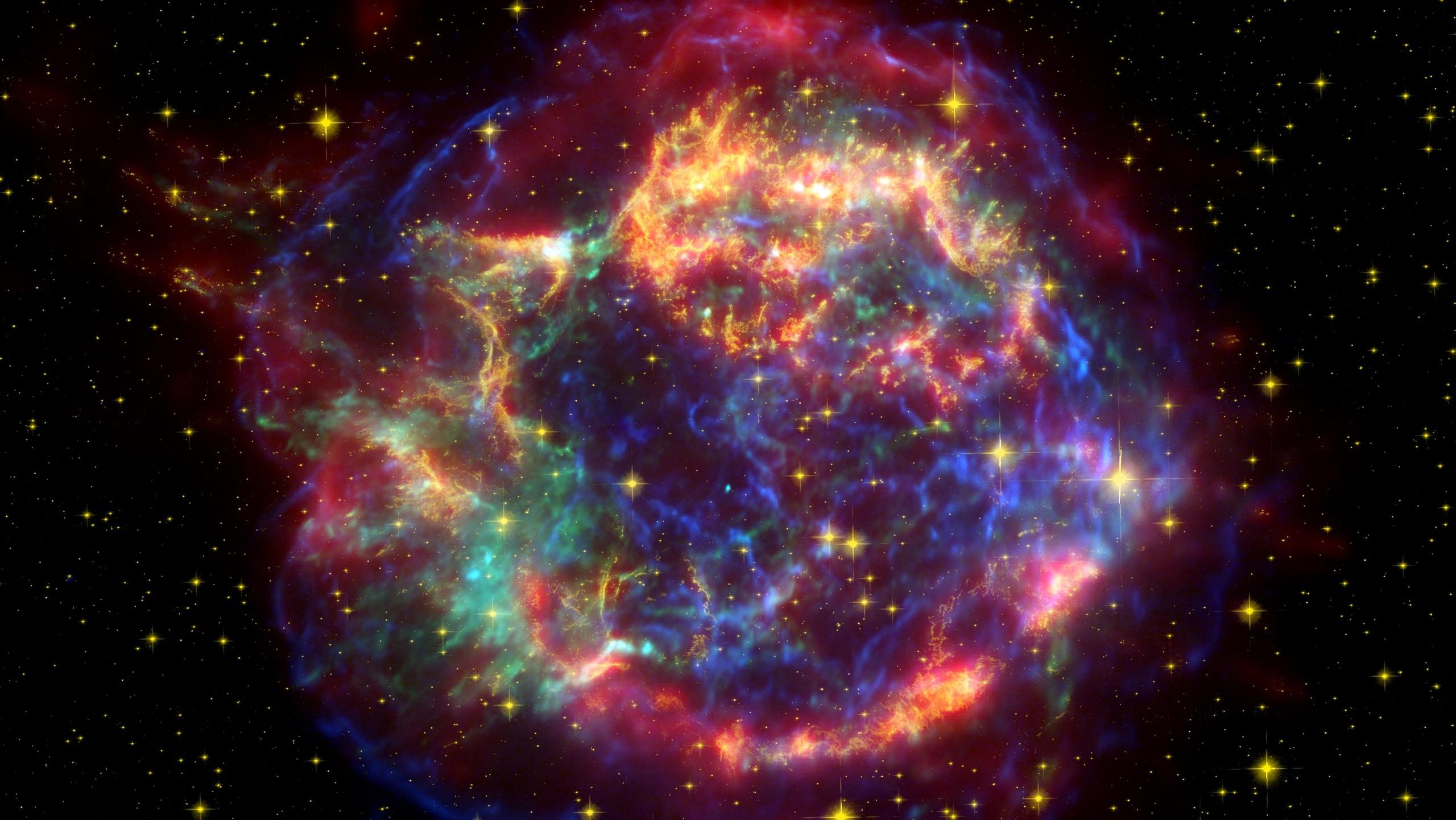

Jonathan Lethem: Yeah, I wait until I have enough to conduct my improvisation or my experiment. I need to have a lot in mind. I don’t work it out on the page. I don’t like notes and outlines. I need to have characters I’m fascinated with, confused by, attracted to, want to spend years with and in a setting that is equally attractive and confusing to me, familiar and strange and I need a voice. I need a kind of a language path into the work. I also need along with those kind of three pieces of equipment for the opening I usually need an image of an ending. I need some kind of set piece or mood or situation or strange moment that while I may not now, in fact, I’m certain not to know how I’m really going to get there, how I’m going to attain it, how I’m going to bring it into being, I know I want to.

And so using those other things I described, the equipment for the beginning of a journey it’s like being loaded up for a mountain climb and you see this kind of slightly cloud-covered top that you’re driven to reach. What lies between you and that top is unknown and that’s excitement. That’s not only fear. It’s a great discovery. It’s a great journey, once you feel the confidence in those things that I’ve just described, to go into unknown territory; to write day after day thinking "I have to figure this out, how do these characters end up where I’m imagining they’ll be and how do I explore this material?" you know. I love that feeling. That’s what I live for now, is to be in the grip of it.

Question: Are there common traps into which inexperienced writers often fall?

Jonathan Lethem: I’m not sure I like to think that there are traps, common or uncommon. There are mostly opportunities and the things that might seem most perplexing or the largest, most immoveable obstacles are also usually areas of potential fascination and obsession.

And writing is not a... you’re not on a journey that has been charted for you, externally. There's no map. There is only you and your own set of impulses. The only directive is to care immensely about stuff that no one else could possibly understand—let alone care about as deeply as you do—and probably wouldn’t even be able to grasp except if you accomplish the task of making yourself into the writer who can bring it forth. I mean when I wanted to write at the outset I was full of these turbulent, impossible-to-paraphrase images of what kind of writing I was going to do. Some of them were nonsense, never to be realized. But the one thing that was certain was that I had to cherish them because there is nothing else except you, in the void, imagining what kind of books you might be able to make people see and understand and enjoy and you’re making...

Thomas Berger was asked why he writes. I’ve already used mountaintop imagery in this conversation and he turned the little famous mountain climbers you know... the Zen reply that the mountain climber gives, “Why do you ascend Everest, because it’s there.” And Berger asked why he wrote said, “Because it isn’t there.” So that doesn’t describe a situation full of traps because traps are laid on a path that someone else has gone. For similar reasons I don’t really think that the image of a writer’s block is a very... is a necessary one. Being blocked, if that it's called, is my job. I sit everyday not knowing.

I mean in a technical sense people will say, “How long did that book take you to write?” Well it took me four years, but it doesn’t mean that I sat typing words for four years of hours. The great majority of that time I spent not even at my desk, but even at my desk, if you had a film of me there, I’d be sitting doing nothing occasionally with little bursts of activity—or sometimes with a cancelled burst of activity. I look like I mean about to... He didn’t do it. It would be like play by play, oh, he, woops, he almost wrote a sentence there.

So being blocked, being uncertain, sitting there not knowing, waiting, abiding with it: this is the work. If you don’t have the tolerance for that you’re in great trouble. If you want to call it a writer’s block... that doesn’t seem a very useful name for that kind of abiding that I think is the essence of the work.

Recorded on September 25, 2010

Interviewed by Max Miller