In his new book A Beautiful Question, theoretical physicist and Nobel laureate Frank Wilczek marries the age-old human quest for beauty and the age-old human quest for truth into a thrilling synthesis: The universe wants to be beautiful. In this video interview, Wilczek delves deep into the fundamental idea of symmetry. Did you know symmetry is much more complex than what we were taught in school? The possible and plausible abstractions of symmetry throughout physics and nature are plenty. The world is full of instances of change without changing.

Frank Wilczek: Symmetry in common usage is a kind of vague term like most terms in common usage. We use it flexibly. The idea of symmetry that has turned out to be extremely fruitful in mathematics and physics and in the fundamental description of nature is a precise distillation of some aspects of the common usage. So it’s not unnatural to call it symmetry, but it’s something very precise that we can describe.

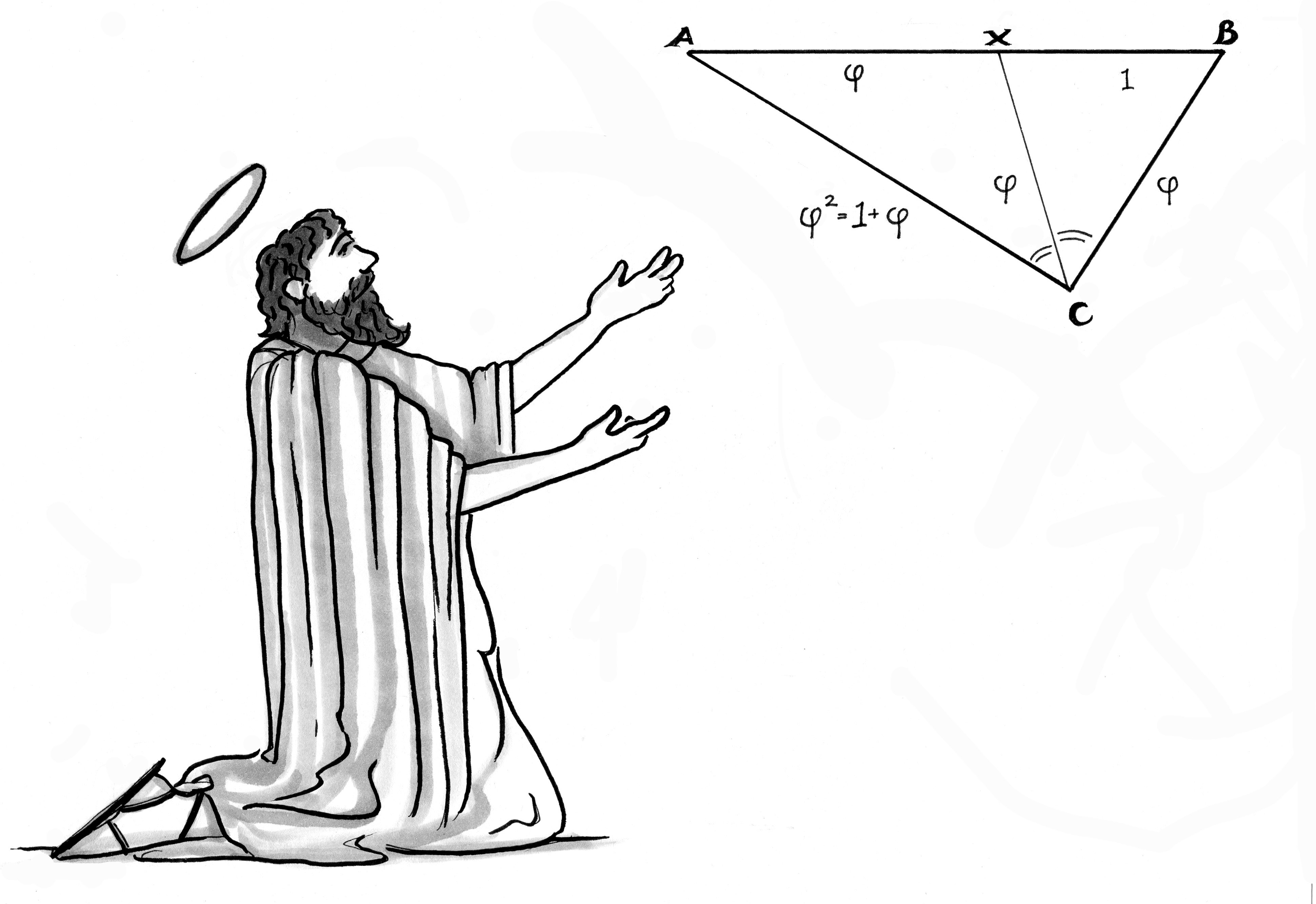

When I say what it is it’ll sound kind of mystical, but it’s actually — I’ll spell it out and you’ll see what I mean. So symmetry in the sense that’s turned out to be fruitful in mathematics and physics and fundamental investigations is change without change. Now you might be puzzled. What does that have to do with symmetry? Well consider a circle. A circle is a very symmetric object. You can rotate it around its center by any angle and although every point on the circle may move, the circle as a whole doesn’t change. And that’s what makes it symmetric in the intuitive sense. You can change it. You can make changes on it which might have changed it, but although they transformed each part of it, don’t transform the thing as a whole. So that’s what makes a circle a symmetric object.

An equilateral triangle, for instance, you can’t rotate through any angle and get the same thing. It’ll change. If you rotate it one-third of the way around though by 120 degrees, it goes over into itself. If you rotate around the center by 120 degrees, it’s the same equilateral triangle. Whereas if you take some lopsided triangle, it’ll never go back to itself until you come all the way back to a trivial transformation. That doesn’t change anything. So change — so a triangle has less symmetry than a circle according to this concept, but some symmetry.

And so you start to see how this concept of change without change matches the intuitive notion of symmetry. The great advantage of that definition is that you can apply it in very broad context not only to describing the symmetry of objects, but to describing the symmetry of physical laws or the symmetry of equations. So, for instance, the theory of relativity is a statement of symmetry that if you change the way the world looks by moving past it at a constant velocity, you change the appearance of everything that’s happening. But the underlying laws are still valid. That’s the assumption of the theory of relativity that drives it and makes it powerful.

The idea that the laws of physics don’t change as a function of time is also a symmetry because it means you can change when you start your clocks and although the time stamps you’ll give to each event look different, the underlying equations will be the same. That’s the way of staying, that the laws of physics don’t change. And similarly with that the fact that the same physical laws apply at different places is a symmetry because you can change your position without changing the way the laws work. So symmetry is a very powerful constraint on our description of the world that nature seems to respect in many ways. Now the kind of symmetry that leads to quantum chromodynamics or general relativity or quantum electrodynamics is, mathematically, considerably more complex but it’s the same idea.

So there are transformations of the equations that change the different terms in them. So they might change an electric field into a magnetic field or a magnetic field into a combination of electric and magnetic that change the way the equations look, but don’t change their consequences. So the equations look quite different — some parts have moved over to the left and some parts have moved over to the right and some things have been multiplied in funny ways. But their consequences, their content is exactly the same. That’s the kind of equations that are like the circles among equations — are ones that have this symmetry property and those are the kinds of equations that turn out to be the ones that appear most prominently in our fundamental description of nature. It’s an extraordinary thing — but that’s not only true, but that’s how we got to the equations in the first place.