Alfred Mele is an American philosopher and the William H. and Lucyle T. Werkmeister Professor of Philosophy at Florida State University. He specializes in irrationality, akrasia, intentionality and philosophy of[…]

The question of human autonomy, the alternate universes that our choices can open up, and the problem of measurement awareness.

Question: Do human beings have free will?

Alfred Mele: Yes. Yes they do. But it turns out that not everybody understands the expression “free will” in the same way. And there are lots of different ways of understanding it. Unfortunately, that makes it hard to just say, “Yes, this is true that isn’t.” One thing philosopher’s spend a lot of time doing is trying to sort out the possible meanings of an expression like “free will,” and the history on the literature on free will is a couple of thousand years old. So, when I talked to the general public, one thing I say about free will is, you can think about it on a sort of gas station model, service station model, So, when you go to the gas station and get regular gas, or the mid grade gas, or the premium. And maybe we could simplify things by thinking of like regular free will. Well, regular free will would be the sort of thing that is presupposed in courts of law when somebody is judged guilty of an offense. So, just that you understood what you were doing, you’re sane and rational, and nobody was forcing, or compelling you to do it, and you didn’t have any medical condition that forced or compelled you to do it. That would be enough to be acting freely. Now, that’s regular free will.

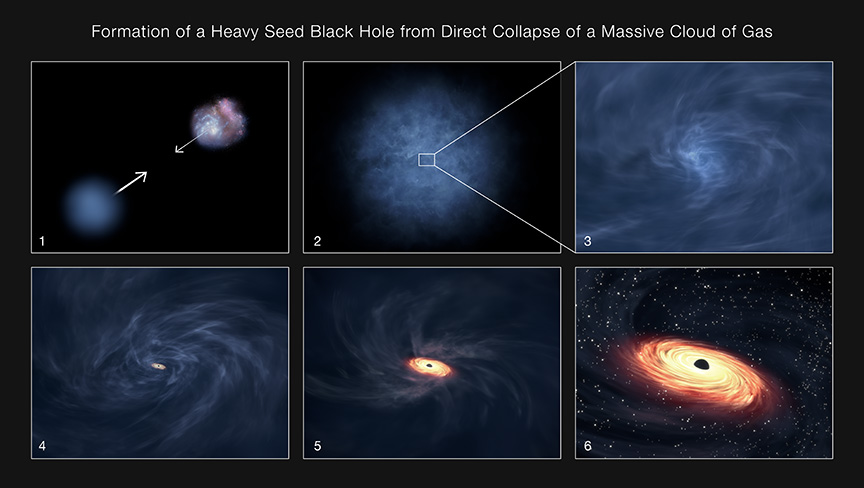

Yeah, okay, so now how do we understand this being able to do otherwise, everything being the same up until that moment? And by everything, I mean the entire history of the universe and all of the laws of nature. So, one way to picture this ability to do otherwise is as follows. If I could have done otherwise at a given moment, then there’s another possible universe. You don’t have to suppose that this universe actually exists. Another scenario where the entire universe is the same up until that moment, and even so, I do something else instead. So maybe what I did was decide to call a taxi, but at that very moment, everything being the same up until then, I could have decided to take a subway instead, and then started heading down the stairs.

Okay. So, some people require that kind of ability for free will. Now, if we’re going to have it, then the brain has to work in such a way that everything being the same up until a given point in time, although I did one thing, I decided to call a taxi. I could have decided to take the subway. And we don’t have good evidence that the brain does work that way, but also, we don’t have good evidence that it doesn’t. Right? So, this is a question that is empirically open. And it could turn out that the brain doesn’t work this way, and then if it doesn’t, then we’re not going to have free will at this mid grade level, but we could still have regular free will.

So, I’m convinced we have regular free will, the mid grade thing, I’m not convinced we have because we don’t have the empirical evidence that we need. But we don’t have it either way.

Question: What is the main experiment that’s driven this kind of free will?

Alfred Mele: So these were originally done starting in the early ‘80’s. They are still being done today. The technology today is better, but it’s the same kind of experiment. What you have are subjects seated in a chair like the one I’m sitting in, and they have this task. To flex the wrist whenever they want. They’re watching a fast clock. There’s dot on the clock and it makes a complete revolution in less than 3 seconds, and they’re hooked up to two machines. One is measuring EEG, electrical conductivity on the scalp. And the other measures a muscle burst on the wrist, it’s an electromyogram. Okay? So, they’re supposed to flex whenever they want and watch this rapidly revolving spot on the clock and then after they flex, they’re supposed to indicate where the spot was on the clock when they first became aware of their urge, intention, decision, to flex. And they indicate it by moving a cursor to that spot on the clock. Okay, is that clear?

All right. Now, when these subjects are regularly reminded to be spontaneous and not to plan in advance when to flex, what you see is that – well, it’s 500 milliseconds, it’s about half a second before the muscle burst, you get a marked change in electrical conductivity on the scalp. You get this ramping up effect. So, that’s about ½ second before the muscle burst. On average, subject say, they first became aware of this urge, or this decision, or intention, or whatever at about 200 milliseconds before the muscle burst. So, if you average out all those responses that they make by moving the cursor, it’s about 206 milliseconds before the muscle burst.

So, Benjamin Libet was the first one to do these studies. And they’re very interesting studies. And what was innovative is he had a way to measure consciousness because he was timing this conscious experience, he thought, right. So, the claim is, then the brain is deciding over a third of a second before the mind becomes aware of the decision. So, conscious free will isn’t driving this behavior, isn’t generating the flexants. And then Libet generalized and he said, “Well, you know, this is the way it is for all behavior. So, the brain unconsciously makes decisions and the mind becomes aware of them only later.”

Now if you think that in order to be acting freely, say it’s an overt action, an action involving bodily motion, like flexing the wrist, a conscious decision has to be causing the behavior and you’re thinking that doesn’t happen, then you’re thinking you never act freely. And so, there is no free will.

Question: What are the mistakes?

Alfred Mele: Okay, it is an interesting result, but what does it really show? Do we know that it’s decisions that are being made at -550 milliseconds, that is about half a second before the muscle burst, as opposed to something else? Well, one thing it could be instead of decisions is a causal process is up and running that increases the probability of a subsequent flexing, but doesn’t raise it to one. So, what you might have then at -550 is a potential cause of a subsequent flexing. And the decision might be made later than -500 or -550. It might even be made around -200, when people say they think they made it. So, that’s one problem, we can’t really correlate this early spike with the decision at that time. And in fact, the way the study is done is what triggered the computer to make a record of the preceding second, or more, of brain activity was the muscle burst. So, there is a muscle burst, and that triggers the computer, okay, make a record of this preceding second of brain activity. But if you use that methodology then you never looked for cases where you get this spike about half a second before, call it zero time, but no muscle motion. You don’t because it’s the muscle motion that triggers the computer to make a record of the preceding activity.

So that’s one problem. And one thing you might wonder too is, so how long does it take a decision to flex your wrist now to generate a muscle burst, or a wrist flexing. And there’s a way to get indirect evidence about that. You could give subjects a reaction time test. So now they wouldn’t be making the decision, but they would be responding to a queue with an intention. So the task might be flexing your wrist whenever that clock changes color from red to green. Okay? And they could be watching the clock too. And it turns out that reaction time studies have been done with a Libet clock. And a mean reaction time, in one study anyway, was 231 milliseconds. There was just a 231-millisecond gap between the emission of the go signal, which was a sound in that study, and the muscle burst. But if it took an intention or a decision something like 550 milliseconds to cause a muscle burst, this result would be very surprising. I mean, here it’s only roughly 200. And of course after there is the go signal, it’s going to take some time to respond mentally with an intention. It doesn’t have to be a conscious intention, but it’s a causal process, so it takes time.

So, that’s another problem. And then there’s a third problem with these studies and it has to do with the measurement of awareness. So, after they flex again, subject moved the cursor to the spot and say that’s when I first became aware of it.

Question: How does measurement of awareness become a problem?

Alfred Mele: So, it must have been two-and-a-half to three years ago now that I gave a lecture on the neuroscience of free will at the National Institute of Health in a motor control unit. The idea was, I do my lecture and then after that they make me a subject in one of these Libet experiments, which was cool. I was interested. And then after that I got out to dinner. They take me out to dinner, but first I have to be a subject in the experiment. So, I gave my lecture then it was time to do the experiment. I was sitting at the chair, they set up the clock and I knew what my task was. And I wanted to pretend to be a naive subject. I wanted to put myself in the shoes of somebody who might do this and not really knowing what is going on. And so, I thought this is what I’ll do, I’ll sit there and watch the clock and I’ll wait for urges to flex my wrist to pop up in me to become conscious, and then as soon as I have such an urge, I’ll flex and then after I flex I’ll move the cursor to where I thought the spot was on the clock when I first became aware of that urge, or intention, or whatever.

So, I was sitting there a little while and nothing was happening. That is, no urges was coming to mind. And I thought, how did they do this? How do these people do it? And then I thought, I better think of a way to do it because otherwise I’m going to be stuck in this chair and I won’t get any dinner. Right? Dinner was next. So, I thought, this is what I’ll do. I’ll just consciously say “now” to myself silently and treat that as an indicator of an urge or a decision, and then I’ll flex and then after I flex, I’ll report where the spot was on the clock when I said “now” to myself.

Okay. So, I had to remember to do this then. Say “now,” flex as soon as possible after I say “now,” and then do the reporting. And at first the neuroscientist said I was flexing in too wimpy a way, so I had to remember to flex hard too. So, okay. I did all of that. And these experiments subjects had to do at least 40 times to get data you could actually read and use. So, I did it about 40 times. And one thing I discovered that although I could pinpoint the spot on the clock to maybe a range of the clock, I don’t know, 20%, 25% of the clock. I couldn’t pinpoint it to an exact tick, let’s say. That was one problem. Also, I had something every definite to look for internally. I was looking for the conscious “now” saying, and I know what that’s like. But subjects who are said, who are instructed to look for an urge or an intention, or decision, or whatever, might wonder, “Well, what the heck was that that I was just experiencing? Was I just thinking about doing it, was it an urge?” So, there could be confusion that they would have that I didn’t have.

Question: What is the bottom line of these experiments in terms of where we stand on that free will scale?

Alfred Mele: Well, these experiments are thought to show that there is no free will. And my main point here is, they don’t show that. For three different reasons really. These judgment times are unreliable, so we don’t really know when people first became aware of the urge. And we don’t have good evidence of what happens at -550 milliseconds, about half a second before the muscle burst, is that a decision is made as opposed to a potential cause of a decision is present. And we don’t have evidence that what’s happening half a second before the muscle burst is sufficient for subsequent muscle bursts. So, it just leaves free will wide open.

Another thing too is, notice what we’re studying here. We’re studying relatively trivial actions. Wrist flexions or mouse button clickings and decisions to do things now. And it may be that free will mainly isn’t at work in that dimension in our lives, but mainly is at work in broader dimensions when we’re thinking about maybe back to students they’ve been accepted into different graduate schools with different scholarship offers and they are thinking about which one to take. Or, maybe thinking about whether to propose marriage, or not, or whether it’s time finally to get the divorce or what house to buy. You know? It maybe that free will is more involved in things like that then in wrist flexions and the like. And then, now this is not a criticism of the scientists who do this work, but with the technology we have now, if you’re going to be studying something similar to free will, it looks like you’re going to be in this domain and not the domain of choosing graduate schools, buying houses, proposing marriage.

Alfred Mele: Yes. Yes they do. But it turns out that not everybody understands the expression “free will” in the same way. And there are lots of different ways of understanding it. Unfortunately, that makes it hard to just say, “Yes, this is true that isn’t.” One thing philosopher’s spend a lot of time doing is trying to sort out the possible meanings of an expression like “free will,” and the history on the literature on free will is a couple of thousand years old. So, when I talked to the general public, one thing I say about free will is, you can think about it on a sort of gas station model, service station model, So, when you go to the gas station and get regular gas, or the mid grade gas, or the premium. And maybe we could simplify things by thinking of like regular free will. Well, regular free will would be the sort of thing that is presupposed in courts of law when somebody is judged guilty of an offense. So, just that you understood what you were doing, you’re sane and rational, and nobody was forcing, or compelling you to do it, and you didn’t have any medical condition that forced or compelled you to do it. That would be enough to be acting freely. Now, that’s regular free will.

Yeah, okay, so now how do we understand this being able to do otherwise, everything being the same up until that moment? And by everything, I mean the entire history of the universe and all of the laws of nature. So, one way to picture this ability to do otherwise is as follows. If I could have done otherwise at a given moment, then there’s another possible universe. You don’t have to suppose that this universe actually exists. Another scenario where the entire universe is the same up until that moment, and even so, I do something else instead. So maybe what I did was decide to call a taxi, but at that very moment, everything being the same up until then, I could have decided to take a subway instead, and then started heading down the stairs.

Okay. So, some people require that kind of ability for free will. Now, if we’re going to have it, then the brain has to work in such a way that everything being the same up until a given point in time, although I did one thing, I decided to call a taxi. I could have decided to take the subway. And we don’t have good evidence that the brain does work that way, but also, we don’t have good evidence that it doesn’t. Right? So, this is a question that is empirically open. And it could turn out that the brain doesn’t work this way, and then if it doesn’t, then we’re not going to have free will at this mid grade level, but we could still have regular free will.

So, I’m convinced we have regular free will, the mid grade thing, I’m not convinced we have because we don’t have the empirical evidence that we need. But we don’t have it either way.

Question: What is the main experiment that’s driven this kind of free will?

Alfred Mele: So these were originally done starting in the early ‘80’s. They are still being done today. The technology today is better, but it’s the same kind of experiment. What you have are subjects seated in a chair like the one I’m sitting in, and they have this task. To flex the wrist whenever they want. They’re watching a fast clock. There’s dot on the clock and it makes a complete revolution in less than 3 seconds, and they’re hooked up to two machines. One is measuring EEG, electrical conductivity on the scalp. And the other measures a muscle burst on the wrist, it’s an electromyogram. Okay? So, they’re supposed to flex whenever they want and watch this rapidly revolving spot on the clock and then after they flex, they’re supposed to indicate where the spot was on the clock when they first became aware of their urge, intention, decision, to flex. And they indicate it by moving a cursor to that spot on the clock. Okay, is that clear?

All right. Now, when these subjects are regularly reminded to be spontaneous and not to plan in advance when to flex, what you see is that – well, it’s 500 milliseconds, it’s about half a second before the muscle burst, you get a marked change in electrical conductivity on the scalp. You get this ramping up effect. So, that’s about ½ second before the muscle burst. On average, subject say, they first became aware of this urge, or this decision, or intention, or whatever at about 200 milliseconds before the muscle burst. So, if you average out all those responses that they make by moving the cursor, it’s about 206 milliseconds before the muscle burst.

So, Benjamin Libet was the first one to do these studies. And they’re very interesting studies. And what was innovative is he had a way to measure consciousness because he was timing this conscious experience, he thought, right. So, the claim is, then the brain is deciding over a third of a second before the mind becomes aware of the decision. So, conscious free will isn’t driving this behavior, isn’t generating the flexants. And then Libet generalized and he said, “Well, you know, this is the way it is for all behavior. So, the brain unconsciously makes decisions and the mind becomes aware of them only later.”

Now if you think that in order to be acting freely, say it’s an overt action, an action involving bodily motion, like flexing the wrist, a conscious decision has to be causing the behavior and you’re thinking that doesn’t happen, then you’re thinking you never act freely. And so, there is no free will.

Question: What are the mistakes?

Alfred Mele: Okay, it is an interesting result, but what does it really show? Do we know that it’s decisions that are being made at -550 milliseconds, that is about half a second before the muscle burst, as opposed to something else? Well, one thing it could be instead of decisions is a causal process is up and running that increases the probability of a subsequent flexing, but doesn’t raise it to one. So, what you might have then at -550 is a potential cause of a subsequent flexing. And the decision might be made later than -500 or -550. It might even be made around -200, when people say they think they made it. So, that’s one problem, we can’t really correlate this early spike with the decision at that time. And in fact, the way the study is done is what triggered the computer to make a record of the preceding second, or more, of brain activity was the muscle burst. So, there is a muscle burst, and that triggers the computer, okay, make a record of this preceding second of brain activity. But if you use that methodology then you never looked for cases where you get this spike about half a second before, call it zero time, but no muscle motion. You don’t because it’s the muscle motion that triggers the computer to make a record of the preceding activity.

So that’s one problem. And one thing you might wonder too is, so how long does it take a decision to flex your wrist now to generate a muscle burst, or a wrist flexing. And there’s a way to get indirect evidence about that. You could give subjects a reaction time test. So now they wouldn’t be making the decision, but they would be responding to a queue with an intention. So the task might be flexing your wrist whenever that clock changes color from red to green. Okay? And they could be watching the clock too. And it turns out that reaction time studies have been done with a Libet clock. And a mean reaction time, in one study anyway, was 231 milliseconds. There was just a 231-millisecond gap between the emission of the go signal, which was a sound in that study, and the muscle burst. But if it took an intention or a decision something like 550 milliseconds to cause a muscle burst, this result would be very surprising. I mean, here it’s only roughly 200. And of course after there is the go signal, it’s going to take some time to respond mentally with an intention. It doesn’t have to be a conscious intention, but it’s a causal process, so it takes time.

So, that’s another problem. And then there’s a third problem with these studies and it has to do with the measurement of awareness. So, after they flex again, subject moved the cursor to the spot and say that’s when I first became aware of it.

Question: How does measurement of awareness become a problem?

Alfred Mele: So, it must have been two-and-a-half to three years ago now that I gave a lecture on the neuroscience of free will at the National Institute of Health in a motor control unit. The idea was, I do my lecture and then after that they make me a subject in one of these Libet experiments, which was cool. I was interested. And then after that I got out to dinner. They take me out to dinner, but first I have to be a subject in the experiment. So, I gave my lecture then it was time to do the experiment. I was sitting at the chair, they set up the clock and I knew what my task was. And I wanted to pretend to be a naive subject. I wanted to put myself in the shoes of somebody who might do this and not really knowing what is going on. And so, I thought this is what I’ll do, I’ll sit there and watch the clock and I’ll wait for urges to flex my wrist to pop up in me to become conscious, and then as soon as I have such an urge, I’ll flex and then after I flex I’ll move the cursor to where I thought the spot was on the clock when I first became aware of that urge, or intention, or whatever.

So, I was sitting there a little while and nothing was happening. That is, no urges was coming to mind. And I thought, how did they do this? How do these people do it? And then I thought, I better think of a way to do it because otherwise I’m going to be stuck in this chair and I won’t get any dinner. Right? Dinner was next. So, I thought, this is what I’ll do. I’ll just consciously say “now” to myself silently and treat that as an indicator of an urge or a decision, and then I’ll flex and then after I flex, I’ll report where the spot was on the clock when I said “now” to myself.

Okay. So, I had to remember to do this then. Say “now,” flex as soon as possible after I say “now,” and then do the reporting. And at first the neuroscientist said I was flexing in too wimpy a way, so I had to remember to flex hard too. So, okay. I did all of that. And these experiments subjects had to do at least 40 times to get data you could actually read and use. So, I did it about 40 times. And one thing I discovered that although I could pinpoint the spot on the clock to maybe a range of the clock, I don’t know, 20%, 25% of the clock. I couldn’t pinpoint it to an exact tick, let’s say. That was one problem. Also, I had something every definite to look for internally. I was looking for the conscious “now” saying, and I know what that’s like. But subjects who are said, who are instructed to look for an urge or an intention, or decision, or whatever, might wonder, “Well, what the heck was that that I was just experiencing? Was I just thinking about doing it, was it an urge?” So, there could be confusion that they would have that I didn’t have.

Question: What is the bottom line of these experiments in terms of where we stand on that free will scale?

Alfred Mele: Well, these experiments are thought to show that there is no free will. And my main point here is, they don’t show that. For three different reasons really. These judgment times are unreliable, so we don’t really know when people first became aware of the urge. And we don’t have good evidence of what happens at -550 milliseconds, about half a second before the muscle burst, is that a decision is made as opposed to a potential cause of a decision is present. And we don’t have evidence that what’s happening half a second before the muscle burst is sufficient for subsequent muscle bursts. So, it just leaves free will wide open.

Another thing too is, notice what we’re studying here. We’re studying relatively trivial actions. Wrist flexions or mouse button clickings and decisions to do things now. And it may be that free will mainly isn’t at work in that dimension in our lives, but mainly is at work in broader dimensions when we’re thinking about maybe back to students they’ve been accepted into different graduate schools with different scholarship offers and they are thinking about which one to take. Or, maybe thinking about whether to propose marriage, or not, or whether it’s time finally to get the divorce or what house to buy. You know? It maybe that free will is more involved in things like that then in wrist flexions and the like. And then, now this is not a criticism of the scientists who do this work, but with the technology we have now, if you’re going to be studying something similar to free will, it looks like you’re going to be in this domain and not the domain of choosing graduate schools, buying houses, proposing marriage.

Recorded on January 5, 2010

Interviewedrn by Austin Allen

Interviewedrn by Austin Allen

▸

2 min

—

with