Pioneering environmentalist Stewart Brand lays out a doomsday scenario for global warming—and a best-case scenario that’s also “pretty grim.” So why is he still smiling?

Question: What’s a realistic best-case and worst-case scenario for climate change?

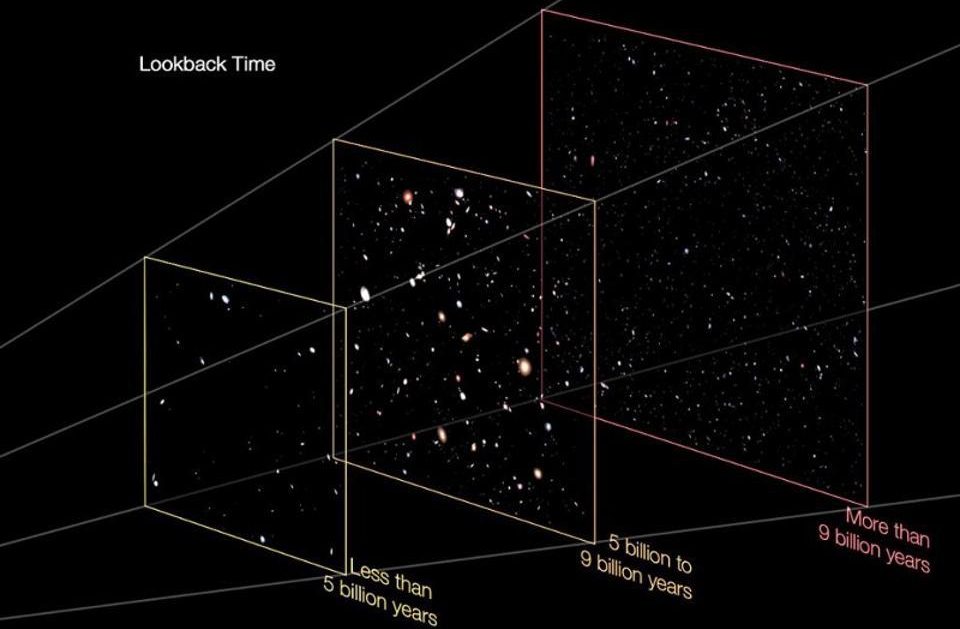

rnStewart Brand: The worst-case scenario for climate, and where the environment might go, in this century is James Lovelock's. He did a book called the Vanishing Face of Gaia; he's the Gaia hypothesis guy. And he's basically saying there's good indication from past records that the earth might re-stabilize at a slightly higher temperature, 5°C warmer than now and then level off again. One problem with that is the carrying capacity for humans in that world is about a billion to about a billion and a half people. In other words, the difference, six or seven billion at that point, would be killing each other off over vanishing resources because of drought and rising sea levels and so on. So that's a future which we can see right now in **** of basically drought is war. That's how it plays out. It's resource wars, it's chaos wars, it's environmentally failed states, it's a really ugly world. And I don't think many environmentalists would be the ones to be a part of the one or one and a-half billion at the end. It would be military people. That's a hard-fought world.

rnThe best-case future, I don't think we've actually figured out yet because the current idea of the best case is that we use a whole lot of renewable and nuclear and everything else and basically get, as someone named Saul Griffiths says, thirteen terawatts of new, clean energy as basically replacing coal, and to some extent natural gas and oil. That involves tens of thousands of square miles of solar farms and wind farms and reactors and geothermal and on and on and on. And when you add it all up and it’s pretty horrifying to contemplate building and contemplate connecting all of it to, by grid to where the people are, which is not usually where the wind or the sun is. And doing all of that in a political environment which is still debating whether or not we even have the climate issue and time is wasting.

rnSo, the best case so far is actually pretty grim, and then that forces me back to why is James Lovelock optimistic, why am I still smiling? It may well be that the experience that we had in England and in America during the second world war gives us perhaps an unwarranted optimism that, you know, this is 1938 and we're doing various forms of Munich and pretending to ourselves that the problem is not as deep as we thought but lots of people are realizing and muttering to each other, you know the problem is really, really serious and it can become quite terrible and we don't know what we're going to do about that. So, there's this strange period of denial, and argument going on. But on the other side of it, if we mobilize and this time there's no human enemy, except ourselves in a weird way, so it would be a world mobilization. It could be a pretty exciting time and it’s actually something that makes me regret being 70 years old because I'll probably miss the most exciting stuff in this century as the world deals with taking hold of the planet at planetary scale with things like geo-engineering, with things like radically redesigned agriculture, radically redesign cities I hope which would be way more fun than even they are now. It's going to be an exciting time, a weird time, an unpredictable time, a fast-moving time, and I hate to miss it.

Recorded on November 17, 2009

Interviewed by Austin Allen