Brainstorming is on the endangered words list, at risk of slipping into ‘buzzword’ territory any day now – although some would argue it’s already there. That’s because everyone is doing it, but many of us don’t quite know how to. According to Bill Burnett, Executive Director of the Design Program at Stanford University, the process is fundamentally misunderstood – it’s about more than sitting in a group expecting genius to unfold. What’s missing from most brainstorming sessions is the notion that this is a skill, not a magic trick.

Here are 3 practical suggestions that Burnett has put forth In the past: start brainstorming with games and improv activities to limber up creative team thinking; create an environment that encourages wild ideas without any negative feedback or reality checks; have a realistic expectations for a team to improve over time. How many garage bands sound good at their first practice? How many chefs get a Michelin star for their first meal? You don’t win Olympic Gold straight off the couch. It’s a popular and true sentiment that it takes 10,000 hours to become an expert at something, and while most of us will never have to time to build up that mother of a timesheet, fortunately we can borrow the wisdom that Burnett has cultivated over his many years at Apple and Stanford.

In this video, Burnett explains how to use brainstorming in an actionable way, why crazy ideas are so necessary to break out of thought clusters (which the human mind is wired to get stuck in), and how to ultimately make a conceptual leap forward to your next brilliant idea.

Bill Burnett and Dave Evans’ book is Designing Your Life: How to Build a Well-Lived, Joyful Life.

Bill Burnett: Everybody kind of knows the rules of brainstorming. You get four or five people together. By the way you can’t brainstorm with 20 people. Everybody has to be able to see each other. I think of brainstorming like a jazz ensemble. Maybe you can have a trio or a quartet. A quintet maybe. Past that you can’t play jazz. It’s just too complicated, too many people. So we get together and they often, you know, come up with a question and they brainstorm for a while and they go great, that was fantastic. And then there’s all these post-its or all these notes on a whiteboard. And somebody says I’ll take a picture and they take a picture with their cell phone. And then that’s where ideas go to die. Ideas just go to die on cell phones.

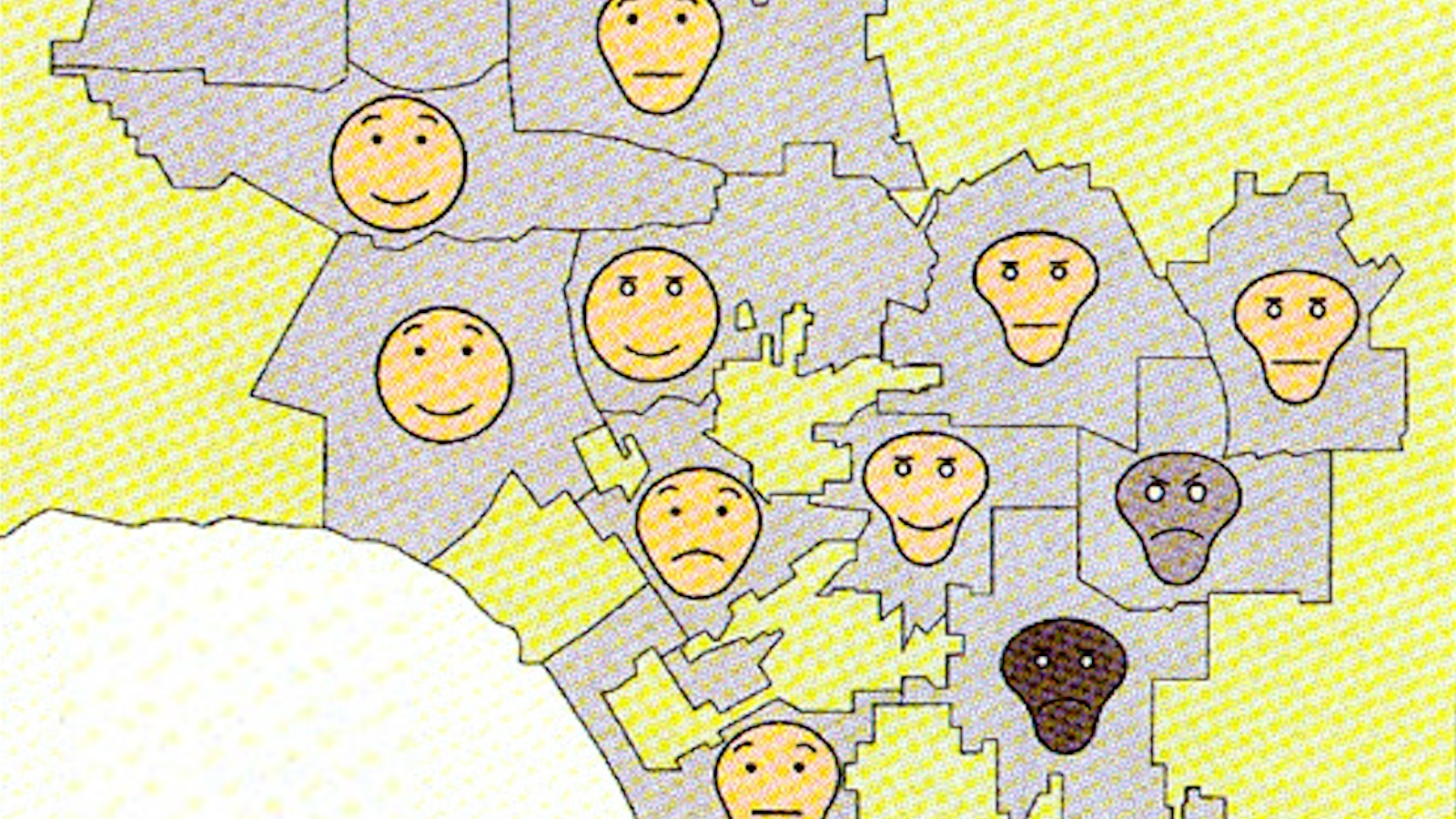

Somebody’s got a picture and they all walk away. And then I ask them well what happened? They said well we had a brainstorm. I said well what was the result? They said well we had a lot of ideas. What are you going to do with it? And they haven’t really made it actionable. So here’s the thing. Brainstorming works great for coming up with lots of ideas and very diverse ideas, particularly if you have a really good jazz team that can really play off of each other. But, you know, at the end of a good brainstorm – when we run it at the D School there will be 100-150 post-its on the board. But that’s not the end because you haven’t really done anything. Generating the ideas is relatively simple once you get good at it. Figuring out what you’re going to do with the ideas, putting them into sort of buckets. Often ideas are clustered around certain themes so the first thing we do and the reason we use post-its is then we stop and say okay, the brainstorm is over. Now we’re going to do a little bit of evaluation, a little bit of what we call naming and framing the ideas. We’re going to put them into the cluster – like this cluster is all around one thing, this cluster is all around another thing. These are all wildcards. They don’t cluster at all. We just kind of move the post-its around. And then we try to give them – we try to put the buckets or sub buckets into some kind of a framework and we just give it a name. And the funnier the name the better. These are the crazy grandmother ideas. These are the ideas if ducks could fly or if chickens could fly this is what the ideas would be.

So we give them funny names but the idea is to sort of bring them back down into reality and put them into some kind of framework. Because at the end of my brainstorms if you ask somebody what happened they’ll say we had 150 ideas. It turns out they were in about six different categories and then we ranked the top ideas in each category and we have seven ideas we would really like to build a prototype of because we think these seven ideas ask the most interesting questions around the problem or the space that we’re doing. The same thing with life design. When you finish your three odyssey plans we say find four or five things on the odyssey plans you want to brainstorm because it’s something you’re curious about. I just discovered hey, maybe I want to be a real estate developer or maybe I want to figure out what it’s like to make gourmet cupcakes at a cupcake store. So you’ve got these ideas and now you brainstorm all the different ways that you could create a prototype around those ideas. And then you name those, bring them back out of crazy land into something that’s actually real. And then you have something you can work with.

So at the end of my brainstorms people will literally we’ll say I’ve got 110 ideas and five categories, down to six top ideas and we’re going to build four prototypes. That’s an actionable brainstorm. And then you do the prototypes and you get some new data and the world tells you something that you didn’t know. And then you get to brainstorm again. But brainstorming just for its own sake is kind of a misunderstanding of the process. Now a lot of times people will say I have trouble with the notion of wild ideas. Why do you have to have crazy ideas? Because no one’s going to use the idea. Well what if there was no gravity, how would we solve this problem? That’s one of the prompts I throw. When people are stuck I give them prompts. What if you were an elephant? How would you do this? How would you use a mouse if you were an elephant? How would you do this if there was no gravity? And they have some crazy, crazy idea. The problem is our brains want to cluster ideas very tightly around some core central thing. And no matter how many times we brainstorm if we don’t change the parameter of that thing we’ll get ideas that are roughly clustered around the same thing. To make these big conceptual leaps, to start a new cluster, a new center of ideas you really need to kind of break out of your box. And the only way to do that is to come up with something that’s so stupid it makes no sense at all.

And then you have a bunch of ideas there and then you have a bunch of ideas there and a bunch of ideas there. You can always bring the wild idea back. An example we did, we did an example brainstorming. This isn’t probably the way it worked but for a while people were trying to figure out how do you solve poverty in India. And the idea was we’ll give money to rich people, they have companies, they’ll employ people, there will be a trickledown effect and poor people will eventually get saving. People have been doing that for a long time and nobody – it didn’t work. Then a crazy guy named Muhammad Yunus said what if we give money to people who have nothing. Give money to people so poor they probably can’t pay it back. And that’s micro lending. Now I mean his idea wasn’t to give it to people who can’t pay it back but the big shift was instead of this trickle down thing what if we just give this woman $50 and she runs a cell phone service in her village and that lifts her out of poverty. And I’ll ask her to hire five other people to do cell phone service. It was a completely radical idea that came from upending the whole model, right, that you give money to the top of the pyramid and it trickles down. And his idea was just no, let’s just float it down to the bottom of the pyramid and it’ll trickle out. And that’s been one of the most successful innovations in poverty reduction and in finance. So it’s things like that where you really need a brand new idea that requires a wild idea to get it started. And then you can always bring it back and find ways to make it implementable.

If you think about it the whole micro lending thing now seems like it’s a good idea. At the time people thought he was crazy. Why would you give money to poor people? They can’t pay it back. But he understood the social contract of I mean micro lending has a lower default rate than regular lending because of the social contract of people, particularly if you give it to women. You don’t give money to men. They’re not reliable. I’m sorry. The statistics are not good in my sex’s favor. They’ll just drink it away or they go hire women. And women, you know, build a nice business and take care of their kids and send them to school. So don’t give money to guys. Let that be a lesson to you so don’t give money to men ever.