Barry Nalebuff explains game theory’s most famous corollary.

Question: What is the origin of the Prisoner’s Dilemma?

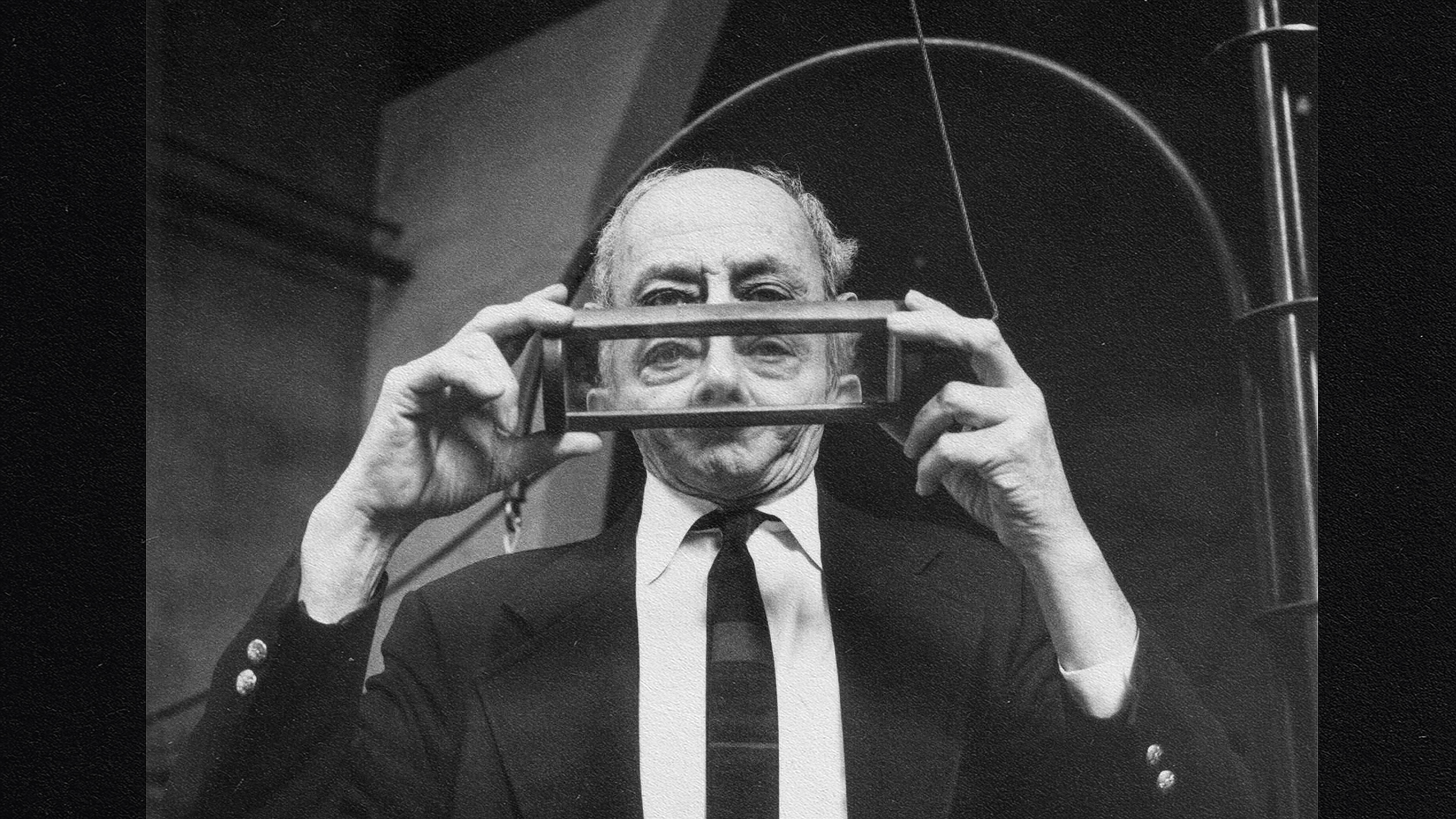

Barry Nalebuff: The Prisoner’s Dilemma goes back to two researchers at RAND, Merrill Flood and Melvin Dresher and it’s a classic story; you’ve seen God knows how many movies.

You interrogate two prisoners separately and the idea is that anyone who confesses is given some leniency, provided they confess first. And, of course, if neither of the two confesses. I have limited evidence against them so they do pretty well. And if they both confess, then the immunity isn’t worth anything.

However, each one is afraid that the other one is going to confess and so therefore confesses, and the police get all the information that they want.

This also raises a couple of things, one that the outcome of the game, in this case confess-confess, can be good or bad from the player’s perspectives, depending on who you are. If you are the prisoners, well, then it’s a disaster. If you are the police or society, it can be a good thing.

We see this with OPEC. The question is, how much oil that any one country choose to bring to the market. And it’s almost the case, no matter what quantities other members of OPEC supply, each one wants to put more on. And then, of course, when everyone does put more, the cartel is much less effective.

Recorded on: Oct 2, 2008