The construction of sophisticated tools has long distinguished the human species from those still content with sticks and rock — or nothing at all. We are creators of things in our essence, says UC Berkeley philosophy professor Alva Noë. But artists are a category of creator apart. They do not make tools useful in the sense that a hammer is useful; nor are their works subject to scientific investigation — insofar as science, and philosophy, strictly distinguish between the observer and that which is observed. Noë says that to create art is to create a “strange tool” — one that actively collaborates with us as we create and examine it. Art unveils who we are as people alive at this moment in history, not merely as objective observers standing outside time.

Alva Noë is a writer and a philosopher who lives in New York City and Berkeley. His work focuses on the nature of mind and human experience. He is the[…]

Whether it’s bacteria or consciousness itself, science and philosophy examine a specific object that stands apart from the observer. Art is more collaborative, says Alva Noë. It changes us as we change it.

▸

3 min

—

with

Related

There’s a fine line between ambition and ruthlessness.

You will need determination, humility, and courage if you are to master anything.

“It’s remarkable how weak the correlation between success and intelligence is.” Here’s what skills do matter, from 3 business experts.

▸

25 min

—

with

Testing is an attempt to measure intelligence. But is intelligence really what’s getting measured? A neuroscientist weighs in:

▸

2 min

—

with

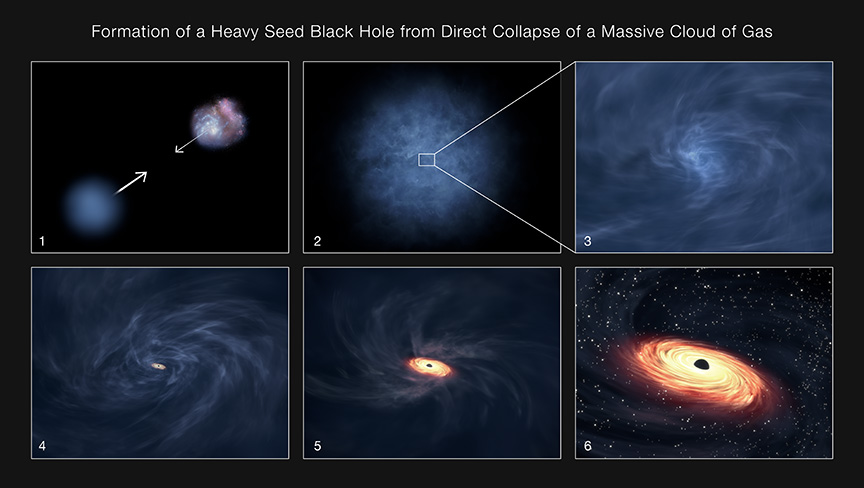

Even in the very early Universe, there were heavy, supermassive black holes at the centers of galaxies. How did they get so big so fast?

Alva Noë: Artists make things not because the things they make are special, but because making is special for us. We are makers. We are, as human beings, manufacturers. If you go back 30,000 years to the dawn of the psychologically modern human being, what seems to inaugurate that beginning is precisely this explosion of making practices, of tool-making and tool-using practices and pictorial practices and linguistic practices and clothing. We are makers and I think that artists make things to unveil that fact about ourselves. So I say that works of art are strange tools. They’re not just more tools with this or that function or application. They’re tools that in their strangeness are meant to exhibit the place that tools and technology have in our lives.

Too often, I think, when we come to thinking about art if we’re scientists or cognitive scientists or philosophers is we think of art as if it were a phenomenon, something that we can put under glass and explain. The view that I’ve come to is that actually art is itself its own research practice. It’s itself a way of trying to understand the world and ourselves. And that a better strategy for trying to really get a handle on the questions that interest us — What is art? Why does art matter so much? What does the fact that it matters so much tell us about ourselves? — is actually to look at art as our collaborator rather than the object of our investigation. The art situation becomes an opportunity to really put one’s own perceptual consciousness or other aspects of one's consciousness, one's understanding sort of interview for oneself. And that’s one of the reasons why I like to say that art is something like a philosophical practice. Because what I’ve just said about art really is paradigmatically philosophical. This idea that art or philosophy are somehow in the business of unveiling us to ourselves and in doing that, it’s supplying us with resources to change.