ERIC TOPOL: Technology can't enhance humanity, that it's depersonalizing, that it's going to detract. I actually think it's just the opposite in medicine, because if we can outsource to machines and technology, we can restore the human bond, which has been eroding for decades. So what I mean by deep medicine is really a three part story: The first is what we call deep phenotyping. And that is a very intensive, comprehensive understanding of each person at every level. So that's the idea of knowing all about their biology, not just their genome, their microbiome, and all the things the different layers of the person, but also their physiology through sensors, their anatomy through scans, their environment through sensors as well, and then traditional data.

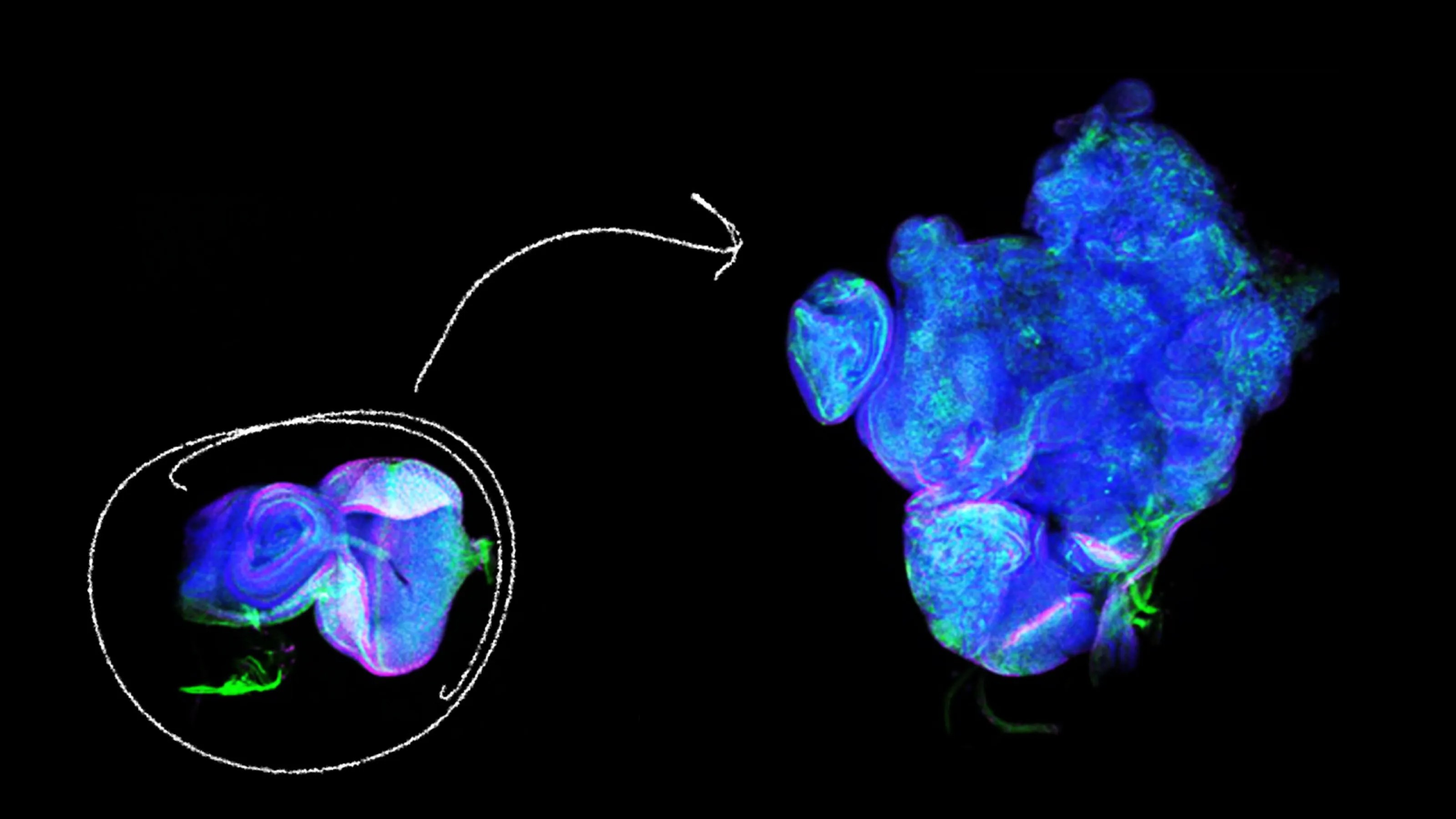

So that's deep phenotyping. Now, no human being can process all that data, because it's dynamic, and it's actually quite large to deal with. That's why we have deep learning. That's a type of artificial intelligence which takes all of these inputs and it really crystallizes, distills it all. And that gets us to deep empathy. And the deep empathy is when we have this outsourcing to machines and algorithms. We have all of this data, and we now can get back to the human side of this connection. Well, where deep learning works the best today is with images. And so medical images are especially ideal because it turns out that radiologists miss things in more than 30 percent of scans that are done today. So in order to not miss these things, you can train machines to have vision better than humans. The difference here is that the radiologists can put more context in it, but the machines, they're very complementary.

They can pick up things that radiologists wouldn't see, like a nodule on a chest X-ray or an abnormality on an MRA that would be missed because radiologists read 50 to 100 scans per day. There's many times that we just don't see things. So when you bring the two together, you get the best economy. It doesn't mean we're going to eliminate the need for radiologists. It's going to make the accuracy and the speed much better. And what I project is that we're going to see a time when radiologists move out of the basement in the dark and actually connect with patients, because they want to see patients. They want to be able to share their expertise, and they don't have a vested interest about doing an operation or procedure. They just want to report what they find and communicate that. So I think we're going to see a reshaping of radiology because of this remarkable performance enhancement through AI.

There's a lot of use of AI in the hospital setting, because when patients come in, and trying to predict what's going to happen, we're not so good at that generally in medicine. So almost everything you can think of there have been algorithms tested. One example is sepsis. So what's going to happen? Does the person have sepsis, a serious infection? Are they going to decompensate and possibly die from sepsis? We're not so great at that, it turns out, by algorithm. But what we have learned is that we can use the same machine vision, whether it's nurses, doctors, people who are circulating in a room of a hospital, to see whether or not they're doing appropriate handwashing, and to set off a signal that, no, it wasn't done and needs to be done. So there's lots of things about patient safety with machine vision.

So for example, preventing falls, seeing that someone's walking is unsteady. Another great example is in the intensive care unit. Some people can pull out their breathing tube, and now we have machine vision that can monitor that so that we don't have a nurse that has to be in the room all of the time. Well, the biggest thing that we need down is the gift of time. Rather than to have this AI support? And it's at two levels. So if you can get rid of keyboards, or liberate from keyboards, reestablish face-to-face eye contact, that's a good start. It's going to happen. But also the patients now can have algorithms generating their own data, whether it's their heart rhythm, or their skin rash, or a possible urinary tract infection, they can get that diagnosed now by an algorithm. That frees up, again, doctors to take care of more serious matters, and that's what is so exciting if we grab this opportunity, which I don't know if we'll see it again for generations, if ever, because this technology offers that potential. But it won't happen by accident.

If we're not taking on this, really, activism to promote the gift of time and turning inward, as the medical community, if we don't do this, we're going to see even worse squeeze than we have now. This is an opportunity that we just can't miss.