6 ways to be good: What’s behind moral behavior?

Shutterstock

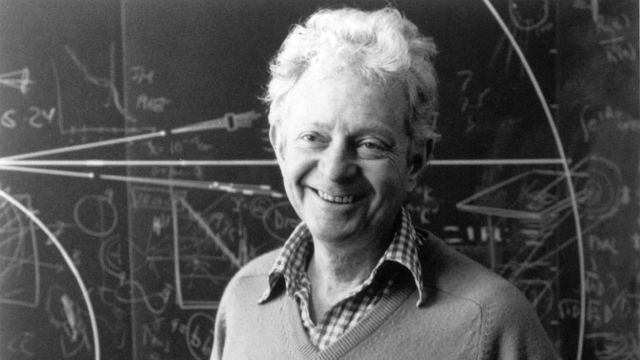

- Lawrence Kohlberg, a famous psychologist, developed this framework to categorize how people think about morality.

- These six stages progress from the simplistic to the complex. Generally, as people age, they progress through the stages, although some unpleasant individuals get stuck.

- Although quantifying morality is challenging and the framework isn’t perfect, spending more time to think about what “good” means to you is valuable.

We’ve all met people who always seem to act based on their own self-interest, who behave well out of fear of punishment, or who think morality and what’s legal are synonymous. On the other hand, some people seem like their moral compass always points true north, even when its inconvenient — or just annoying in conversation.

It’s not a simple task to determine what makes (im)moral people tick. Morality is almost entirely subjective and context-dependent. Despite its inherently slippery nature, psychologists have been trying to pin down what goes into moral behavior for decades. One of the first to do so was a psychologist named Lawrence Kohlberg.

Kohlberg developed a framework consisting of six stages of morality. Broadly, the stages are classified as pre-conventional, conventional, or post-conventional morality. As people age, they pass through — or fail to pass through — each stage, successively developing a more and more nuanced moral system.

People with a pre-conventional sense of morality are likely to litter at music festivals. They won’t be punished for littering, and they won’t be rewarded for throwing their trash away either.

OLI SCARFF/AFP/Getty Images

Pre-conventional morality

Stage 1: Avoiding punishment

People in the first stage of morality act based on how much trouble they’re going to get in. Stealing a car will get you arrested and put in jail, so you won’t steal a car. This kind of thinking has nothing to do with what society thinks about stealing or with what’s “right” in a philosophical sense. Punishment hurts, so don’t get punished.

People in this stage don’t understand how their actions affect others, or why they ought to care about others. They respect authority to the degree that authority can punish them. As a consequence, people in this stage might see others who have been punished and assume that they must have “deserved” it.

Essentially, this is the morality of young children. While most people grow to the later stages as they age, some (terrible and unpleasant) people get stuck at this stage or in the ensuing stages.

Stage 2: What’s in it for me?

The big insight in stage two is that people have different perspectives and needs, but this understanding isn’t very broad. To a stage-two thinker, other people’s interests exist only in the sense that they can be leveraged to further his or her own interests. The mindset here is best described as transactional. What makes behavior “good” is that it is rewarded. In this sense, it’s the flipside of the coin of stage one, where bad behavior is that which is punished.

Like stage one, people who fall into this category are generally young children, but you can also find adults who are stuck at this stage, typically working in politics.

People with a conventional sense of morality abide by society’s rules and consider those rules to define right and wrong.

EDUARDO MUNOZ ALVAREZ/AFP/Getty Images

Conventional morality

Stage 3: Society decides what’s right

At this point, folks start acting like adults. The perspectives of other people begin to matter more, and morality is defined as the social consensus about what is right or wrong.

Because people in this stage understand morality as something driven by the consensus of others, they behave in ways that make them appear good to others. This is sometimes called the “good boy/good girl” stage for this reason.

The thinking here is still self-centered, however. Stage-three thinkers understand that being seen positively by others leads to good outcomes for themselves. This is best exemplified by the “golden rule”: do to others as you would have done to yourself.

Stage 4: Society needs to be maintained

In the previous stage, people behaved well in order to be seen positively and to be treated well in return. This next stage represents something of a leap forward. Rather than seeing things in an entirely egocentric light, a person at this stage of moral development realizes the importance of obeying laws and social norms in order for society to continue to function.

The main motivation here is to keep society running — if one person breaks the law, maybe everybody will do so, ultimately destroying the system that keeps life running smoothly. To an extent, this is still focused on the self, but this style of thinking acknowledges that everyone else’s behavior affects one’s own welfare.

Here, morality comes from the society one lives in. Maintaining that society and behaving morally are one in the same. According to Kohlberg, most people settle at this stage.

People with a post-conventional sense of morality understand that laws don’t necessarily correspond to what’s morally right and are more likely to follow an internal ethical code of conduct. In this image, a crowd of protesters has gathered in front of the Washington Monument as part of the civil rights movement of the 1960s.

ARNOLD SACHS/AFP/Getty Images

Post-conventional morality

Stage 5: Laws are for the greater good

The other stages prior to this point focused on morality as something derived from an external authority. At stage five, people realize that law doesn’t necessarily equal morality.

Stage-five thinkers understand that laws are social contracts — essentially, mutual agreements between individual and the state on guidelines for behavior — rather than absolute, rigid rules to moral behavior.

The main characteristic of this stage is the understanding that laws do not always work as intended, but that they should ideally benefit the most people possible or work towards the general welfare of society.

This is similar to stage-four thinking, that laws must be followed to preserve society. The main difference is that stage-five thinkers acknowledge that other people hold different values and opinions that might not jibe with a given social group. A stage-four thinker might consider outsiders to be a threat to their society, but stage-five thinkers understand that society’s laws must take into account the fact that people have wildly different values. In theory, modern democracy is based on this kind of moral thinking.

Stage 6: Universal principles

Unexpectedly, laws are no longer much of an issue for people at this stage of moral development. A person who manages to reach this point has developed a comprehensive ethical code built on principles of justice, rights, fairness, and equality. A stage-six person doesn’t have to worry about obeying laws: their behavior will automatically fall in line with those laws that are just, and for laws that are unjust, it is their moral duty to disobey.

For the rare person to develop this kind of moral center, their behavior is always based on what’s right, not what’s expected of them, what’s legal, what avoids punishment, or what’s in their best interest.

Some caveats

Although it’s an interesting framework, Kohlberg’s six stages of moral development isn’t perfect. Kohlberg placed people into these categories by posing various moral dilemmas to participants and then having trained interviewers ask questions about what should have been done. This means Kohlberg’s research was prescriptive — based on what people think should have been done after the fact — rather than predictive — based on what people would actually have done. Many researchers argue that morality isn’t based so much on reasoning, but rather on intuition and instinct. Somebody who exemplified stage six principles in response to a dilemma might actually have reacted in line with stage one principles.

This framework also focuses on justice to the exclusion of other moral qualities. Notice how many of these stages refer to the law, when many instances of moral behavior have nothing to do with the law. The framework also hasn’t been shown to work consistently in different cultures and was based on a sample consisting entirely of men. Kohlberg actually said that women get stuck at stage three; researchers since then have argued that Kohlberg’s system instead focuses on a male-oriented concept of morality.

Despite these criticisms, taking an honest look at these categories and thinking of where one falls sheds light on a subject most people probably don’t think about. Most people try to be good as much as they can, but little attention is paid to what “good” is. I think I’m not alone in feeling that the world could use a little more self-reflection.