The 3 myths of mindfulness

- Mindfulness is hugely popular today — unless you’ve been living on the Moon, you’ll have come across it.

- One philosopher has argued that certain unchecked types of mindfulness are deeply flawed.

- Here we look at three reasons why you might want to be mindful of mindfulness.

You’ve been invited to dinner at a friend’s house where they’ve prepared a lovely beef bourguignon. You all sit down at your places, ladle out your portions, and get to work. Halfway through dinner, you suddenly notice something odd has happened to the person sitting across from you: She has completely stopped talking. What’s more, she is staring at you with the dead eyes of a Halloween mannequin.

“Are you alright?” you ask, a touch nervously. She starts sharply as if you’ve broken her reverie.

“Oh, sorry,” she says. “I’m trying mindful eating. I’m focusing on every bite.”

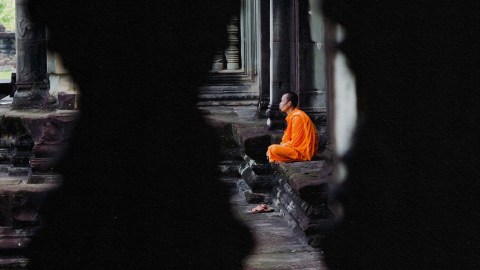

Unless you’ve been living on the Moon for the last ten years, you have probably heard of mindfulness. Schools and companies worldwide have been riding high on the mindfulness wave. Mindfulness apps get millions of downloads and mindfulness coaches are paid millions of dollars. People swear by its efficacy.

The problem, though, is that mindfulness is a building constructed on shaky foundations. According to Odysseus Stone from the University of Copenhagen, mindfulness makes three big philosophical errors.

1. Not all thoughts are equal

If you’ve ever experienced some guided mindfulness, you likely heard something like this: “Imagine your thoughts are like cars, and you are watching them pass. Here comes a thought. There goes the thought. Do not pause for too long on any thought. Let them come, notice them, and then let them go.” Mindfulness is all about not attaching too closely to any one thought. It’s about acknowledging thoughts but not indulging them.

But is this right? Sometimes this strategy is undoubtedly good. Losing sleep over a presentation you have in the morning or obsessing over a dentist appointment is silly. But other times our thoughts are not things to take lightly. As Stone writes: “Take, for example, feelings of anger that we might have about the policy decisions of the Danish government. Is it beneficial to view such emotions as if they are passing clouds in the sky with little importance or relation to reality?” In other words, sometimes our thoughts and feelings are vitally important. They help us navigate the world and tell us the best way to behave. After all, it’s a foolhardy person who isn’t a little bit scared of venomous snakes.

2. Your attention is not only yours

The second key element to mindfulness is that you need to take control of your attention. It is built on the idea that we have supreme power over how and what we focus on. Our minds are like a spotlight, and we are the spotlight operators. We choose to focus on our anxieties. We choose to dwell on the negative.

The problem, though, is that this is a vastly oversimplified view of the psychology of attention. Attention is often beyond your control. It might be that some wizened Shaolin monk can ignore everything the world throws at him, but the vast majority of people cannot. Attention is a social problem. Consider smartphones, for instance. Yes, you can choose not to buy a smartphone, but a world without smartphones is a world with different implications regarding our collective attention. The 1990s had a different attention economy. As Stone puts it: “According to some philosophers and cognitive scientists… Our attention is highly dependent on our embodiment, and is embedded in a material and social context.”

3. It is impossible to “seize the day”

The third dubious piece of mindfulness wisdom is the idea that we should live in the moment and seize the day. Focus on the now, and spend as little time as is practically possible on the past or the future. The problem, though, is that the idea of “now” doesn’t actually exist in how we experience the world.

As the French philosopher Henri Bergson knew, we do not experience time like some calendar or clock. We do not live “in” the current hour. Instead, we live according to duration. Time is constantly moving forward, and it makes no sense to talk about a “now” without reference to both the before and the after. Human psychology depends on the wealth of experience, memory, and learned behaviors from the past. All of our actions and thoughts are framed by a concern for the future. In Stone’s words: “If our experiences and actions are to be coherent and to make sense and make sense to us, they will have to refer to our past and future in one way or the other.”

The baby in the bathwater

Of course, none of this is to say mindfulness is bad. There’s a reason millions of people around the world practice it. There’s a reason people chew their beef bourguignon with peculiar intensity. It works. For the vast majority of the trivial worries in our lives, letting go of thoughts is sound wisdom. Taking greater control and responsibility for what you give your attention to is great advice. And spending less time dwelling on the past or worrying about the future will probably make you more relaxed.

As with almost all philosophy and self-help fads, moderation and sensible application is key.