“Terminalism” — discrimination against the dying — is the unseen prejudice of our times

- Philosopher Philip Reed defines "terminalism" as discrimination against the dying, or treating the terminally ill worse than they would expect to be treated if they were not dying.

- Examples of terminalism include denying necessary medical care to the dying based on cost, prioritizing life extension over quality of life in allocation protocols, and granting experimental treatments only when conventional options have failed.

- Reed argues that terminalism is unjustified and highlights the importance of recognizing the rights and value of dying individuals as human beings.

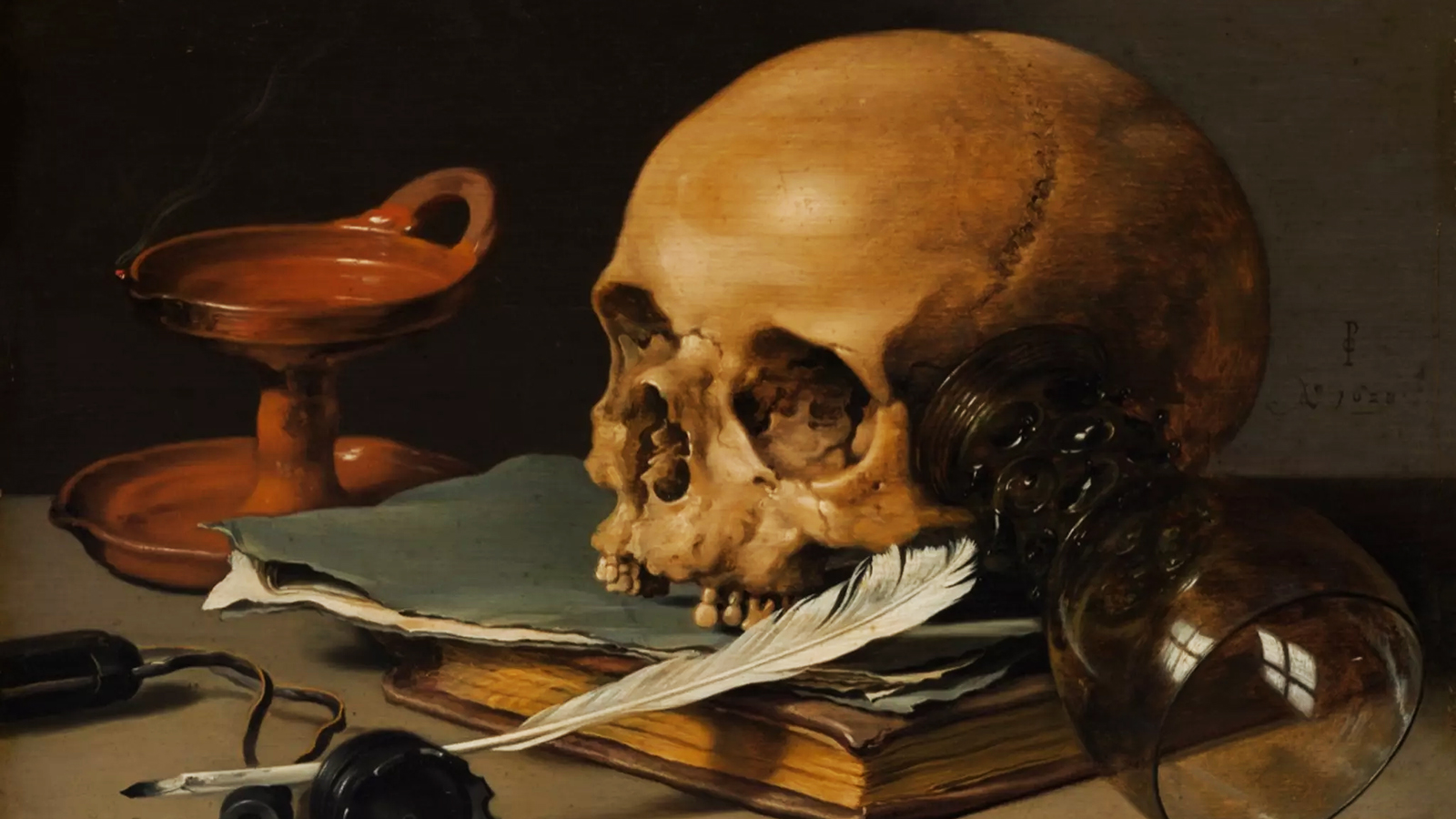

When you are dying, you are placed in a hospice. Often, this is a real, brick-and-mortar hospice with palliative care and psychological support. At other times, though, the hospice is a metaphorical one. The terminally ill are ignored by those too awkward or scared to face them. They are told not to work or exert themselves in the slightest. The dying exist as ghosts and live in the hinge space between society and “on the way out.” When you’re told you’re going to die, you become invisible.

This has led the philosopher Phillip Reed to coin the expression “terminalism.” For Reed, terminalism “is discrimination against the dying, or treating the terminally ill worse than they would expect to be treated if they were not dying.” In other words, it involves treating those in a hospice — literally or metaphorically — as second-class citizens.

Here we look at three examples of terminalism and consider to what extent, if at all, it can be justified.

How quickly are you dying?

It’s both trite and existentially invigorating to say, “We are all dying.” If life is seen in terms of a finite number of heartbeats, we are all ticking our way to the grave. But if we are to discuss the rights of the terminally ill, we need to define “dying” a bit more closely. Reed discounts those who are likely to die in the extremely short-term; there is little to be said about discrimination against someone on an operating table or who is bleeding out on a battlefield.

Reed argues that those who will die imminently are not “socially salient,” which is to say that their state of dying will not be long enough to affect social relationships, social norms, or legal attitudes. As he puts it, “because membership in the group is, by definition, extremely short-lived, it cannot play a role in a wide range of social contexts for any one person.”

Therefore, if we are talking about discrimination as a social phenomenon, we have to talk about those who have been terminally ill for long enough to experience some kind of discrimination. Reed more or less settles on the established legal position of the U.S. and many in the West, in which “terminally ill” is defined as anyone who will die in the next six months from an illness.

Everyday terminalism

In an article for the Journal of Medical Ethics, Reed goes on to list examples of terminalism in our legal and social systems. Here, we look at three.

Too expensive to bother. If you want to receive hospice care, which is overwhelmingly palliative, you have to be in the last six months of your life. Yet, if you receive hospice care, you will stop taking (or not be offered) life-prolonging drugs, even when those drugs have palliative effects. Why bother wasting money extending someone’s life when their death is inevitable? What’s more, 78% of American hospices turn away patients requiring high-cost care. But, as Reed says, “There is a strong social consensus that people should not be denied necessary medical care simply based on the cost, and yet this happens regularly for the dying (at least if they also need hospice care).”

Allocation protocols. During COVID, most hospital systems developed rules of allocation for life-saving drugs and apparatuses. Those who were dying were at the bottom of the list. When an institution is suffering from limited healthcare resources, such as organs for transplant, they will often be biased against the terminally ill. Reed criticizes protocols that prioritize life extension over quality of life, as they implicitly undervalue the immediate needs of dying patients.

“Right to try” laws. While these laws ostensibly empower terminally ill patients to access experimental treatments, they also highlight a paradox. They grant a certain freedom only when the patient has been deemed beyond the help of conventional medicine, potentially relegating them to the status of test subjects when traditional care options are exhausted.

Reed suggests a useful thought experiment to highlight the prejudices in each case. He writes: “It is easy to see the discrimination if we change the eligibility criteria to another socially salient group: if we said that [the above applied] exclusively for racial minorities or trans people, the message would be that we do not care about protecting racial minorities or trans people.” We do not care about protecting the dying.

Justifying terminalism

Reed believes that a lot of people will find it somewhat ridiculous to call these instances a kind of discrimination. When presented with limited resources, surely it’s better to focus on those who have longer to live? In other words, isn’t it okay to value longevity over the moribund?

Reed calls this a structural “terminalist prejudice,” with little philosophical justification for it. He argues that “many of us tend to think, explicitly or implicitly, that a worthwhile life involves both the kind of life that has a future and also enables a person to ‘contribute meaningfully’ to society.”

We don’t want to see ourselves as cruel or prejudiced. We don’t want to accept that we are privately and socially devaluing human life based on our terminalist biases. Dying people are human beings as well. They have brothers and sisters; sons and daughters; or wives and husbands. They read books, watch TV, talk, laugh, and reminisce. If all humans have rights, the dying have rights, too. They are valuable in themselves, not for some abstract, unknown “contribution” they might make. As Reed puts it, “The reason that terminalism matters is that dying persons matter.”