The problem of other minds: a disturbing world of polite, smiling zombies

- The problem of other minds asks how it is that we can be sure that other people have mental lives when we can only infer that this is the case from behavior and testimony.

- John Stuart Mill argued that we know others’ minds by analogy, but is this a strong argument?

- With artificial intelligence and animated movies, what grounds do we really have for ascribing mindedness to sentient-looking beings?

There is no sore throat in the world quite as bad as your sore throat. Yesterday, when Sylvie from next-door claimed she had a sore throat, you are not even sure if you believe her. She is not in pain in the same way that you are in pain, right?

In fact, how do you know that Sylvie isn’t lying about her feelings all of the time? She is a bit of an egoist, so it wouldn’t surprise you. It is exactly the kind of manipulative trick she would pull. And the same goes for her husband and kids — how do you know that they all have that complicated mental life they say they are having? And what about your best friend? Or your brother? Or your own spouse, even? How can you be sure they have minds like yours?

This is the philosophical problem of “other minds” — a favorite Gordian knot of philosophers from those omni-agnostic Skeptics to René Descartes.

No way of knowing for sure

The problem of other minds boils down to standard epistemological skepticism, which means to say that it is one of those, “How do we know?” questions that philosophers love. In this case, we have to ask how it is that we know other people have thoughts or minds at all.

The only way we know what a particular mental state is like is because we also have them. You know what love or grief is because you have experienced them. You understand what it is to remember something or to construct an imaginary unicorn because you have done it. We are directly acquainted with ourselves, and ever since Descartes popularized the idea in his Meditations, we have privileged, first-personal access to our own thoughts. I can, in his terminology, “Turn my mind’s eye upon myself.”

And yet, this is not how we know about other people’s mental states. For those of us who aren’t (yet) comic book mutants or Jedi masters, we do not have a magic eye or telepathic ability to read another’s thoughts. Instead, we are left to infer or assume others’ minds indirectly. We most often do this by witnessing their behavior — screams for pain, hand reaching for “wanting that,” and so on — but also through reports or testimony. We assume, in normal circumstances, that when someone says, “I’ve got a sore throat,” that they actually have pain (unless it is Sylvie, of course).

We believe that when someone gives an account of a mental life, they really are experiencing that mental life.

I know you by analogy

The problem is that this gap between another’s thoughts and our knowing about them gives enough room for that insidious doubt.

First, behavior can be notoriously difficult to read at times and often misleads as an account of someone’s mental state. Outside of stock photos or Looney Toons, few people get red-faced when angry or stream fountains of tears when sad. Second, what grounds do we have for believing both someone’s behavior and their testimony? We all definitely have lied about our mental states before (like when asked, “What are you thinking about?” and you reply, “Oh, nothing.”) What proof do we have that others aren’t frequent liars? Indeed, we only need to turn on the TV to see actors or animated dogs pretending to have mental states that they do not. So, by what means can we differentiate between mindedness and the imitation of mindedness? If having a mind can sometimes be a charade, there is no way of telling when it is not.

One way we can claim to know another’s mind is by analogy. This is a method that says, “If X is similar to Y in this respect, they are likely similar in other respects too.” This was the method preferred by British philosopher John Stuart Mill in accounting for other minds. So, given you look human like me, behave like me, talk like me, have a brain like me, and so on, then it is highly likely that you also have thoughts like me.

This argument might be pretty convincing in establishing a probability or likelihood, but it is unlikely to satisfy a diehard skeptic. The problem is that analogies are strong or weak depending on their repeatability or frequency. For instance, we know that lots of animals with long, sharp teeth are also carnivores. Therefore, given the regularity of this, if we meet an unknown animal with sharp teeth, we can infer, by strength of analogy, that they are meat eaters.

Yet we do not possess this wealth of data for “minds.” In fact, we only have one sample — our own. So we are left to extrapolate from one case of known thoughts to every other person we meet. This seems like a pretty weak analogy.

AI and the problem of other minds

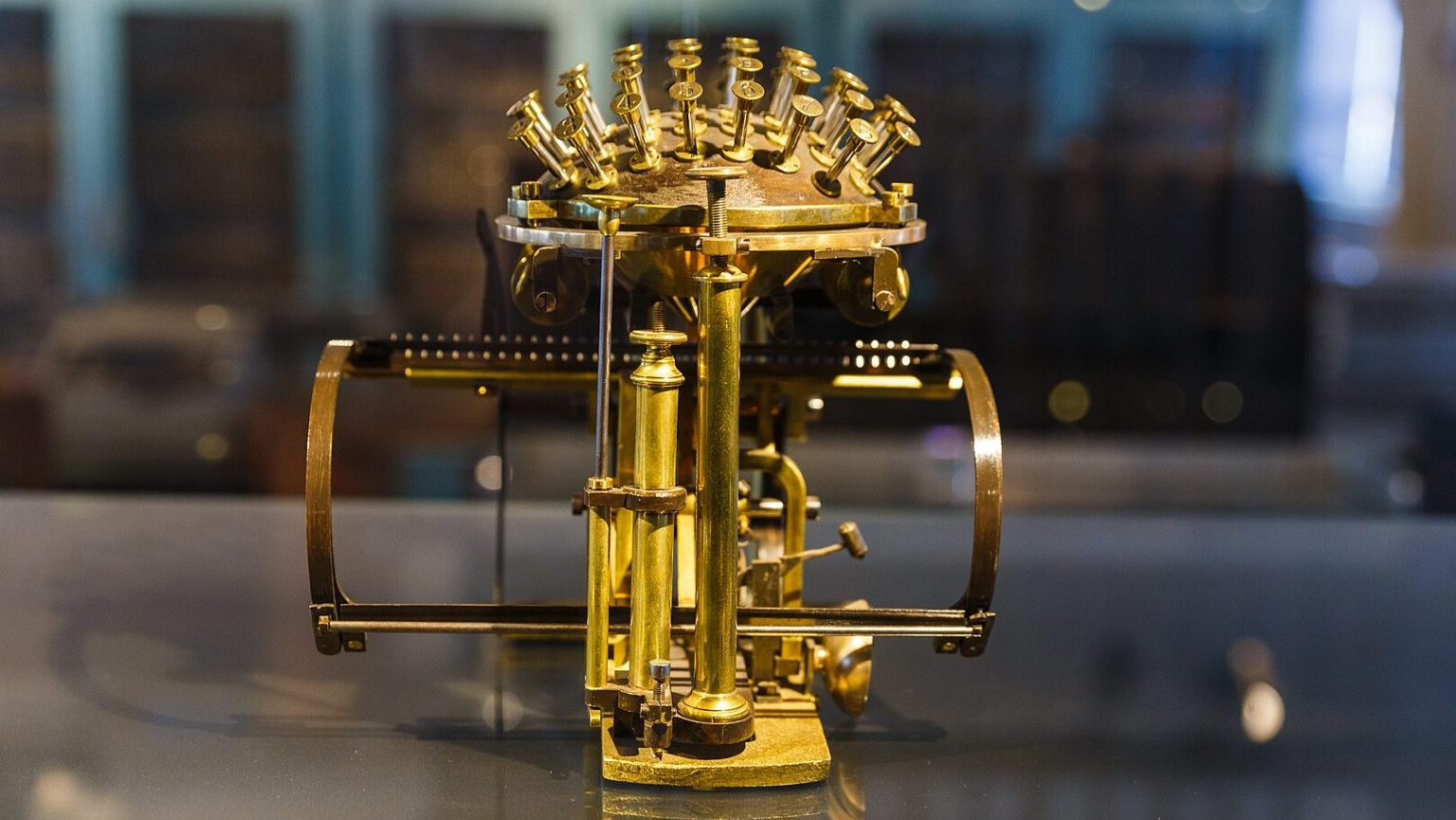

Today, the problem of other minds gets new and even trickier consideration. What was once the concern only of science fiction and imagination is now coming closer to reality: artificial intelligence. If robots or AIs start to mimic behavior that is almost indistinguishable from humans, or if they give testimony or accounts of an inner mental life, should we therefore not ascribe them a mental life like we do other humans?

Odder still is that it often takes a conscious effort to deny non-humans mental states. We naturally assume mindedness when we witness it. If we did not do this, then all animated movies, from Wall-E to Pinocchio, would utterly fail to engage us. These movies and TV shows work precisely because of the ease with which we label others as minded.

And what’s wrong with that? What reason, philosophical or otherwise, is there for saying that your Uncle Paul has mental states, but Sonny, Ava, or Hal 9000 do not? It is fine to be skeptical or accepting about both, but we ought really to give good reasons if we are inconsistent one way or the other.

Jonny Thomson teaches philosophy in Oxford. He runs a popular Instagram account called Mini Philosophy (@philosophyminis). His first book is Mini Philosophy: A Small Book of Big Ideas.