Philosophy has lost its transformative power. Here’s how we can revive it.

- Philosopher Shai Tubali argues that modern philosophy, often abstract and detached, rarely offers actionable wisdom on its central question: How should we live?

- Many ancient philosophical texts were designed not to inform the mind, as modern ones do, but “to form the soul.”

- Tubali argues that philosophy should be lived through action, not only dissected in the abstract.

In my early twenties, I fell headfirst into what I thought would be a grand love affair with academic philosophy. With starry eyes and a mind parched for meaning, I eagerly dove into a bachelor’s degree, sampling courses on the philosophy of religion, language, and South Asia. I naively envisioned professors as wise sages who would illuminate life’s thorny questions of identity, purpose, and meaning. Instead, my romantic notions smashed against the cold, hard reality of professors droning from papers and skimming the edges of my deepest existential yearnings. They delivered knowledge, yes — but wisdom? That precious spark was nowhere to be found. Disillusioned and aching, I abandoned my studies after just three months.

Fast forward two decades, and I returned to professional philosophy, older, wiser, and with a sober understanding: transformative teachings would need to be sought elsewhere. This time, I advanced rapidly through doctoral and postdoctoral research, mastering the demands of academia while accepting its limitations. Yet, the core of philosophy within the academy hadn’t changed. Take, for instance, a recent conference on practical philosophy. Despite my tempered expectations, I couldn’t help but hope that philosophy might finally step down from its ivory tower into the vibrant chaos of lived experience. But as the lectures began, I was once again let down. The discussions were brilliant, laden with intricate arguments and esoteric concepts, yet stubbornly tethered to the abstract. The speaker, glued to his prepared notes, never once paused to ask: What do Kant’s musings on aesthetics mean for how we experience beauty in the everyday? Or better yet, how do we live these ideas, moment by moment? It was a reminder that while philosophy is unparalleled in posing questions, it often stumbles when faced with the urgent task of applying them to life itself.

It’s not hard to imagine countless philosophy students sitting where I once sat, their brows furrowed, haunted by the same nagging question: What does any of this have to do with living? They listen to ideas meticulously stripped of life or funneled into disembodied academic papers, knowing full well that if they dared to raise a hand and ask, “How should I live?” they’d likely be met with a blank stare — or worse, a reading list.

Philosopher Bryan Van Norden captures this frustration perfectly in his book Taking Back Philosophy. He points out that contemporary academic philosophers often lose sight of philosophy’s most burning, human question: What way should one live? Instead, they risk reducing their field to what he aptly calls “intellectual masturbation.” He warns that many philosophers are consumed by self-contained intellectual puzzles, viewing the real-world implications of their research as an unwelcome intrusion. Ask them how their work impacts the world — or their own lives — and you’re more likely to get an eye-roll than an answer. What they fail to see, Van Norden argues, is their responsibility to explain why their studies matter and how philosophy might arm students for the inevitable storms of life.

For all its brilliance, academic philosophy often feels like an endless exercise in chasing its own tail — thinking about thoughts in a dazzling maze of abstraction. Instead of wrestling with life’s raw questions, it turns into research about philosophy, not the act of doing it. Here, success is measured by rigorous analysis, systematic investigation, and crafting arguments so airtight they leave no room to breathe. But for a wisdom-hungry student, this polished precision feels hollow — a sterile echo of a field that once dared to grapple with the heart of existence. Philosophy, a discipline born to confront the profound ambiguity of human life, seems to have tidied itself up so much that it’s forgotten how to get its hands dirty.

Now, with AI effortlessly churning out philosophical theories and crafting comparative essays, academic philosophy might be staring at its own existential reckoning. Philosopher Sven Nyholm put this to the test, asking ChatGPT, “What would Martin Heidegger think about the ethics of AI?” To his amazement, the AI generated a “fairly impressive short essay” on the spot. With a touch of humor and humility, Nyholm confessed that “ChatGPT did a better job than at least some — maybe even many — of the students in my classes.” He even admitted that the AI’s response might have outshined what he could have conjured up on the fly. This amusing yet unsettling anecdote, shared in 2023, came at an early stage in the evolution of large language models (LLMs). Imagine what lies ahead. In just a few years, it could become nearly impossible to distinguish between an essay authored by a seasoned academic and one seamlessly woven together by a remarkably clever machine. If AI can assemble intricate ideas from disparate schools of thought faster and more effectively than most humans, what becomes of philosophy’s proud claim to intellectual rigor?

The bold question we must ask is whether this is what philosophy was ever meant to be. Perhaps the discomfort so many feel toward modern academic philosophy exists for a good reason. Can we envision a radically different kind of philosophy — one that centers on the love of wisdom, shapes individuals, and offers practical guidance on living the good life? The good news is that we don’t have to stretch our imaginations too far. This is precisely what philosophy was when it first took root in classical Greece — and in ancient India and China, though they didn’t call it “philosophy” as we do.

Philosopher Colin McGinn recounts an enlightening pattern: When strangers learn he’s a philosopher, they instinctively assume he’s in the business of offering sage advice. These exchanges, he observes, underscore a striking truth: The kind of “knowledge of abstract theoretical matters” that preoccupies modern philosophers has little to do with the “love of wisdom” for which the field was named. In fact, McGinn argues, today’s philosophy is so far removed from its ancient roots that philosophy departments may need an entirely new name.

So, let’s journey back to the Axial Age (800–200 BCE), where philosophy began its life as a vibrant, practical pursuit — one deeply connected to living wisely. By exploring its roots, we can rediscover what philosophy once was, understand how we drifted away from it, and see how it evolved into the theory-bound field we know today.

Philosophy as transformation

When we pick up a work by a classical philosopher, we’re often holding just a sliver of their broader philosophy — like trying to understand a symphony from a single note. Take Plato, for instance. Historians widely acknowledge that his dialogues offer only a shadow of the dynamic, multifaceted philosophy he cultivated within the academy he founded. To truly grasp the essence of classical philosophical discourse, we need to let our imagination leap beyond the text. Picture a way of life where philosophy wasn’t a profession or a niche academic pursuit but a full-bodied, transformative journey aimed at a sublime existence. In this vision, rational argumentation was just one thread in a rich tapestry of practices — less an end in itself and more a tool within a broader, more profound system of living wisdom.

This realization is precisely what jolted Pierre Hadot, the celebrated French historian of philosophy. Like many others, he initially approached classical texts with modern expectations, searching for neatly packaged theories and rigorous systematic arguments. But eventually, Hadot had an epiphany: These works were never meant to compete with modern treatises. They were crafted for students already committed — or considering committing — to a way of life shaped by a philosophical school. These texts weren’t mere vessels of knowledge; they were tools for transformation, designed not to inform the mind but to form the soul.

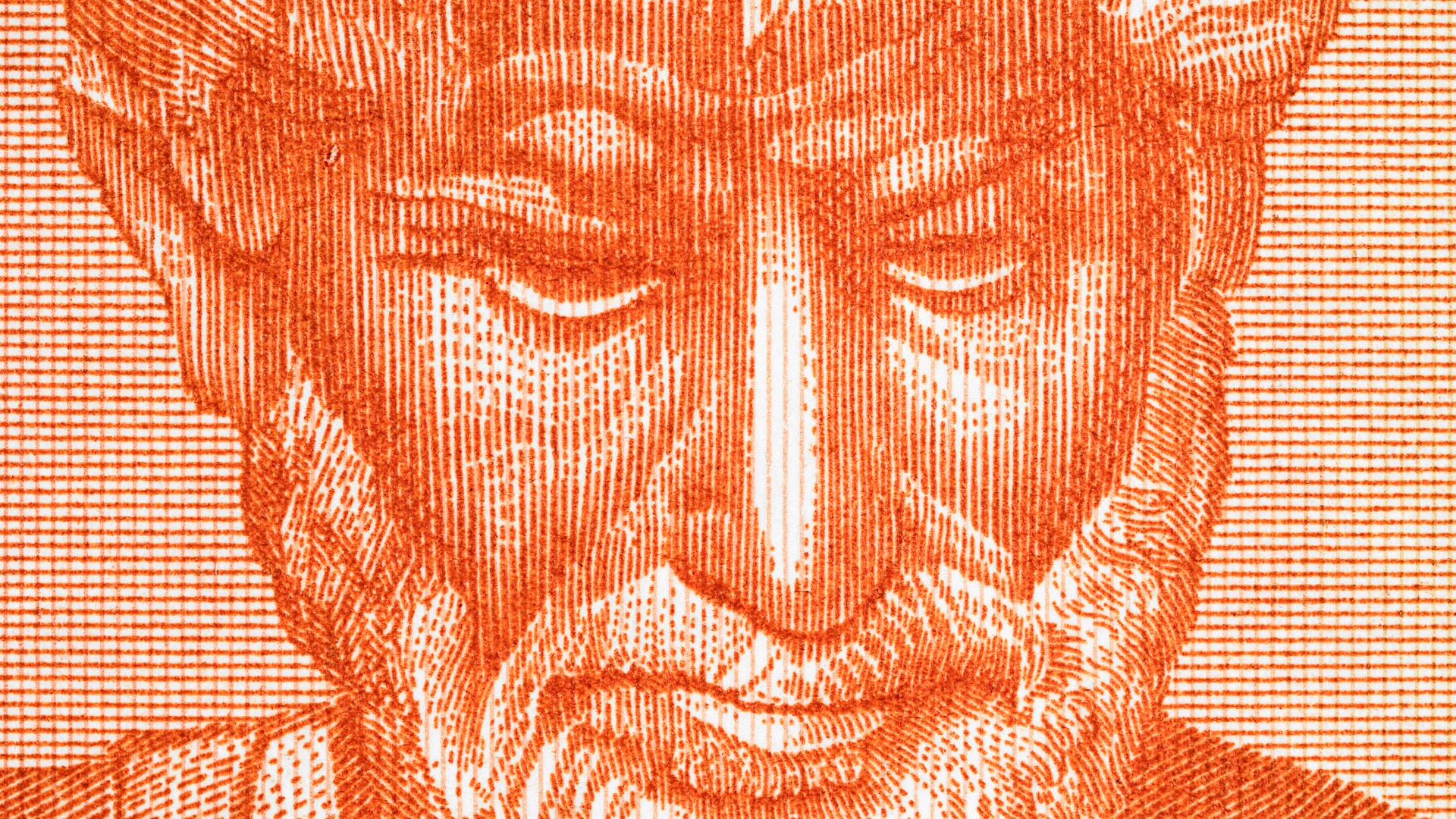

Plutarch, the renowned Greek philosopher and historian, captured this vividly when he spoke of a “continuous philosophy,” one that reveals itself in “acts and deeds,” unfolding “at all times and in all parts, in all experiences and activities.” Consider Socrates as the quintessential example. Can we ever truly separate the philosopher from the human being who lived — and died — the way he did? Plato’s dialogues are steeped in references to Socrates’ singular presence, his deliberate choices, and his unshakable actions. These weren’t mere stylistic flourishes; they were essential to understanding Socrates’ philosophy. When he speaks, his words feel inseparable from his life — his discourse flowing as naturally as breath from the essence of his being.

In Xenophon’s Memorabilia, when pressed to stop questioning and refuting everyone and just declare what justice is, Socrates responds with a smirk-worthy retort: “I never stop showing what things are just in my opinion. If not by speech, I show it rather by deed.” With Socrates, philosophy wasn’t a lecture — it was an ongoing, walking demonstration. When we think of him, we see a man utterly fearless, shrugging off life’s so-called treasures, and famously immune to intoxication. We imagine him standing still for an entire day, lost in meditation, or calmly discussing death and immortality while sipping poison, turning even his last breath into a masterclass on how to live a life true to one’s ideals.

Socrates wasn’t a lone star in showcasing a philosophy that both speaks and lives. In truth, classical Greek philosophy thrived as a vibrant continuum — a tapestry of teaching and practice designed to transform every facet of its practitioners’ lives through committed, embodied exercises. This spirit flowed through Plato’s Academy, Epicurus’ Garden, Zeno’s Stoa, and even the less formal gatherings of the Cynics, Pyrrho, and the Skeptics. What united these diverse schools were five deeply interwoven elements: the cultivation and purification of the mind, practices that bridged the inner and outer realms of life, a foundation of argument and theory, an emphasis on embodied living, and a communal or dialogical dimension that wove people together. Even Aristotle’s Lyceum, with its scholarly penchant for knowledge and theory, wasn’t exempt. For all his intellectual rigor, Aristotle believed philosophy’s ultimate aim was nothing less than divine intellect, true happiness, sublime pleasure, freedom from worry, and a virtuous life.

Each school approached wisdom as a kind of alchemy, refining the mind to reach a specific, luminous state of being. Yet they all seemed to agree on one thing: Wisdom wasn’t just about knowing — it was about finding unshakable peace of mind. Philosophy, from this perspective, became a cure for life’s worries, anguish, and misery. The Cynics believed that human suffering sprang from the shackles of social norms and conventions, so they threw caution — and clothes! — to the wind, forging a life of shameless, fierce independence. Pyrrho, on the other hand, practiced radical indifference, training himself to stay serenely unmoved by anything life threw his way. Epicureans sought to escape the lure of false pleasures, embracing instead the sweet, simple delight of just being alive. The Stoics reached even further, striving to dissolve selfishness and live in harmony with the vast, cosmic order.

Despite their wildly different paths, all these schools shared a common thread: the journey inward. They believed peace came from clearing away the clutter — desires, fears, and distractions — and returning to something pure, natural, and true, like a restoration of the soul’s original health. Plotinus painted this with a striking metaphor: a sculptor chiseling away at a block of marble, not to add anything, but to uncover the beauty already hidden within.

The Greek philosophers weren’t indifferent to building perfectly coherent theories — many put plenty of effort into crafting arguments that aligned their thinking with the cosmic order. But for them, theory was often a means to an end: inspiring an unshakable conviction that could guide their students to live philosophy, not just think it. Their goal wasn’t to explain every detail of reality but to offer just enough clarity to support a way of life. Imagine Socrates on his deathbed, drinking the hemlock and gently persuading his distraught disciples that the soul outlives death. His reasoning wasn’t a dry intellectual exercise; it was a lived truth, meant to free their minds and strengthen their resolve.

For the ancients, philosophy was never about words alone. Wisdom had to leap off the page and into life. Truth wasn’t confined to abstract ideas — it had to be embodied, practiced, and experienced. To reach this state, daily practices were essential. Some were physical, like carefully chosen diets. Others were contemplative, like meditations that calmed the mind or rituals that ordered the emotions.

The Stoics, for instance, had stark but powerful exercises. Epictetus encouraged them to reflect on impermanence by imagining, while kissing their child, that the child might die tomorrow. They also practiced seeing life through the eyes of universal Reason, imagining the entire human world from a bird’s-eye view. The Epicureans, in their quiet retreats, meditated on simplicity — finding joy in plain food, simple clothing, and a life stripped of wealth and ambition. Plato’s Academy added its own soul-shaping practices: preparing for peaceful sleep, finding calm in misfortune, sublimating love, and even rehearsing for death.

For all these schools, action was the beating heart of philosophy. Ideas remained hollow until they were lived. The Greek philosophers had no patience for those who spun clever arguments without applying them to their own existence. A theory’s truth wasn’t proven by its logic but by how deeply it transformed life. As Blaise Pascal once observed, the writings of Plato and Aristotle were the least philosophical parts of their lives. “The most philosophical part,” he wrote, “was living simply and quietly.”

Resurrecting the lost art of living philosophy

Philosophy’s first steps took place during the remarkable Axial Age, a time when ancient Greece, India, and China experienced a seismic shift. The world moved from mythic religions and ritual-based thinking to a new focus on human consciousness and self-knowledge. Suddenly, the gods weren’t holding all the power — humans were. For the first time, people realized they could seek answers within themselves, without relying on priests or rituals. This wasn’t just a rational awakening; it was a bold claim: The human mind could free itself. Misery wasn’t destiny — it could be unraveled through understanding. Happiness became something new: a self-reliant state, not a gift from the heavens. Schools of thought blossomed, all tied to this fresh idea that happiness and freedom were within reach. The great debates weren’t just about knowledge but about how to live, how to be free, and how to truly be happy.

So, how did philosophy drift from its roots as a way of life, becoming a detached and abstract pursuit? Pierre Hadot highlighted three key reasons. First is the timeless tendency of philosophers to seek refuge in words rather than action. Across the ages, many have found comfort in the safe world of theories, avoiding the challenging, sometimes uncomfortable, work of reshaping their own lives. Second, the rise of Christianity reshuffled the landscape entirely. Ancient spiritual exercises, once at the heart of philosophy, were absorbed into Christian practices, while philosophy itself was sidelined — reduced to a theoretical servant of theology, stripped of its practical power to transform lives. Third came the medieval university, which sealed philosophy’s fate. It turned into a technical language for specialists, a discipline more about training experts than inspiring people.

When theory and practice parted ways, humanity lost a vital kind of philosophy — a middle path that combined logic with life. Transformative philosophy wasn’t just about clarity, structure, and reason; it was about using those tools to break through to something profound. It recognized that reason had its limits, treating it not as the destination but as a springboard to liberate the human spirit, shatter rigid thinking, and open doors to entirely new ways of being. It was philosophy in action, reimagining how we experience life and culminating in wisdom through personal metamorphosis.

Today, this spirit is scattered. Self-help books and New Age practices carry the torch of practicality, while academia clings to sterile theories, too timid to explore the Stoics’ exercises or the concept-shattering force of Socratic dialogue. Yet, Western philosophy has still produced individual transformative thinkers outside academic walls who reignited the flame. Think of Nietzsche or Camus, whose fiery visions challenged people to embrace life with raw intensity and carve meaning from its chaos.

Now, with AI cranking out philosophical essays in seconds, philosophy risks fading into irrelevance if it stays locked in barren abstraction. But there’s hope — reviving transformative philosophy. Imagine philosophy returning to its roots, where it wasn’t just about thinking but about living. This is philosophy that meets life head-on, reshaping how we see, feel, and act in the world.

Picture students in philosophy departments practicing Nietzsche’s eternal recurrence, imagining living the same life over and over, learning to say “yes” to every joy and hardship. Or climbing Diotima’s ladder from Plato’s Symposium, moving step by step from earthly beauty to the sublime. These aren’t just ideas; they are experiences meant to change how we engage with life.

Why not bring these practices back into philosophy classrooms? Instead of dissecting theories in isolation, we could teach philosophies as movements of thought, action, and transformation. It’s time to reclaim what New Age spirituality and self-help have borrowed — the soul-stirring, life-altering power of philosophical exercises. A philosophy like this wouldn’t just sit on the page. It would challenge us, liberate us, and make us see the world — and ourselves — in entirely new ways. Isn’t that the philosophy we need now more than ever?