How phenomenology can radically change your perspective on everyday life

- Phenomenology is “the science of phenomena” — or the study of everything that gives our lives meaning.

- Total immersion in the world of what we “do” rather than “think” is a core tenet of phenomenology.

- As observers, we want to analyze what is familiar to people — so familiar that it structures our behavior without ever being something we think about. It feels so normal and true, but when we look at it directly, it often is rather odd.

Phenomenology is “the science of phenomena” and is perhaps the most important philosophical tradition of the 20th century. At its core, it claims that describing the human experience of “things” directly without any filters is possible, and that this description gives us a much better understanding of what it means to be human. We are not looking to understand what any individual feels in a particular moment but rather the whole structure of the way we experience the world. Based on what do we do what we do? The founders of this tradition argue that we humans rarely think abstractly and analytically about life happening around us. We understand very keenly how our world works, but we rarely think about it. In essence, phenomenology is the study of how the human world works and everything that gives our lives meaning.

Phenomenology can unlock the experience of living in a city or the sensation of being a mother. It is whether we see an American flag and regard it with nostalgia and trust or with disdain and anger. As a tool, it can describe the experience of a thing like a truck. Any truck has a weight, color, and shape. Trucks have a physical limit to how fast they can drive and how much they can tow that we can measure. We can think about these data points, but they say very little about what role a truck plays in our lives and communities. Such facts are particularly poor at describing the actual act of driving the truck. As drivers, we engage directly in driving without truly thinking analytically about it. This total immersion in the world of what we “do” rather than “think” is a core tenet of phenomenology. Experience rarely has anything to do with thinking and almost everything to do with being engaged actively in the world.

This might sound unscientific, but it is a highly organized way to explore what things mean to us and how we use different types of equipment in our lives. If you visit a jeweler and show him a diamond ring, for example, he will assess the number of carats in it. That number will give you information about the scientific constitution of the stone, but only phenomenology will shed light on your experience of those carats. What role does this glorified rock play in our lives? Does it make us feel safe? Overwhelmed? Ashamed? Loved? What does it mean to wear it on your hand? How do you feel when you walk around with it? And what are those experiences based on?

What we are interested in is what is most familiar to us, so familiar that it structures our behavior without ever being something we think about. It feels so normal and true, but when we look at it directly, it often is rather odd. When I use the word background, I am referring to the way all of us have a familiarity with the worlds we know well. We stop seeing the background because it is so familiar to us. As observers, we want to analyze what is familiar to people and find out how and why it works.

Consider another example of phenomenology. An hour is always 60 minutes, and 11:00 am is the same time (roughly) every day, but a minute can be experienced as an hour, and an 11:00 am meeting can feel like it is starting at the beginning of the day. How long is a minute in experience time rather than clock time? The abstract measurement of time increments reveals nothing about the way we experience that time. What is it like to live through this one specific minute in this one very specific context? What is our experience of that 11:00 am meeting?

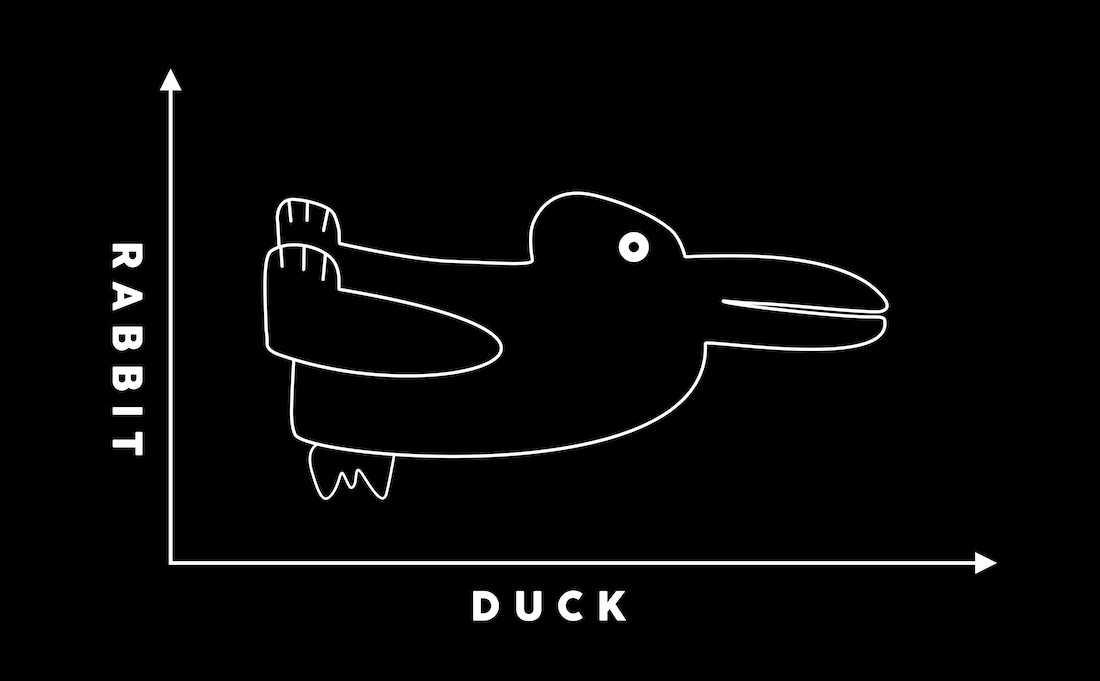

If all of this strikes you as decidedly unscientific — after all, how can you make a science out of the way things are experienced by one person somewhere in the world? — consider it in a different way. Phenomenology will not reveal the essence of something — a car, for example, or a piece of jewelry, or a restaurant — but rather the essence of our shared relationship to that thing. Not everything is important to us all the time. We stand in relationship to the things in our lives, and phenomenology can show us which things matter most and when.

The slogan of phenomenology is “To the thing itself.”

Take the concept of money. Instead of examining it in the physical world — as cellulose with ink printed on it — try to examine it in the human world. Money is a shared language for value. Most of us prefer having more of it rather than having less. Many of us are afraid of it. Some find it arousing, while certain cultures refuse to speak of it out loud or even acknowledge its existence. When banks design accounts for their customers, they typically give people with more money greater access to it. In a banker’s world, it is vital for top clients to have full transparency with their accounts. But if you look more closely at how wealthy people experience their money — how they have it or spend it — a banker’s perspective may not be the most appropriate mindset for designing an account. After all, most people with money don’t want to see it every day. They want to be assured that it is safe, but they don’t have any interest in counting it the way bankers do. In this way, bankers miss an opportunity to have more meaningful relationships with the people they serve because they impose their values on their clients.

The slogan of phenomenology is “To the thing itself.” The idea is to study the thing itself — be it a work of literature, death, family, a car, a vaccine, or the hospital — without preconceived notions, trendy easy answers, or dogma imposed on it. This is how we begin to arrive at the types of observations that lead to insights.