Everyday Philosophy: “Is there anything wrong with trauma dumping?”

- Welcome to Everyday Philosophy, the column where I use insights from the history of philosophy to help you navigate the daily dilemmas of modern life.

- This week’s question concerns the ethics of “trauma dumping,” where someone offloads too much, too quickly, on someone who feels unready for it.

- To answer the question, we look at Jean-Paul Sartre’s idea of advice-giving and Aristotle’s notion of friendship.

I have a friend at work; she’s kind of a friend, but only ever a “work friend.” We have lunch together and get along, but nothing more. Lately, she’s started to spend our lunch breaks ‘trauma dumping’ on me. I don’t mind venting or offloading, but this is more than that. It’s too much. It makes me feel uncomfortable, and I find I don’t want to eat with her anymore. Is she wrong to dump trauma on me?”

— Lisa, London

Friendships are complicated. In some ways, the term “friend” is such a sprawling, overused word that it’s now become pointless. We have work friends, school friends, home friends, best friends, old friends, new friends, parent friends, couple friends, and so on — each with its own definition and rules of engagement. So, we find Lisa in a thicket, trapped by two related issues. The first is, “What kinds of friendships allow what kinds of behaviors?” and, second, “When, if ever, is ‘trauma dumping’ acceptable?”

In an act of incredible philosophical hubris, I’ll try to tackle both. To answer Lisa’s question, I’m going to call upon the existentialist Jean-Paul Sartre to examine what’s really going on here. Then, we’ll look at Aristotle, who does as good a job as any at defining “friendship.”

Sartre: Shifting the burden of responsibility

In his short book, Existentialism is Humanism, Sartre narrates the story of a student who came to him for advice during the Nazi occupation of France. The student asked, “Should I stay home to care for my mother or join the resistance to avenge my brother and fight for France?” Sartre argued that the student didn’t want advice — he wanted Sartre to tell him what to do. He wanted to surrender his freedom and responsibility of choice to someone or something else. “Oh, I couldn’t fight with you because Sartre told me to stay with my mom,” he’d say to his paramilitary friends.

How can we apply Sartre’s point to the case of Lisa? The fact is that when some people offload or trauma dump, they are trying to elicit not just advice but direction. They don’t want someone to just listen; they want them to fix their issues. If Lisa’s friend says, “Oh, I caught my boyfriend texting another girl last night,” she doesn’t want sympathy. She wants to be told what to do. This work friend is shifting the moral burden of choice — the anxiety of freedom — to Lisa. And that’s not fair.

In 1968, the psychiatrist Stephen Karpman introduced the concept of the “drama triangle,” a model for how relationship dynamics can become unhealthy during conflicts. The model describes three main actors in a conflict — the perpetrator, the victim, and the rescuer — and proposes that a drama triangle can emerge when someone casts themselves (reasonably or not) as a victim or a perpetrator, typically as a means to achieve goals that the person might not even be consciously aware of.

So, Lisa’s friend might conceptualize the situation as: “My boyfriend is the perpetrator, I am the victim, and you, Lisa, are my rescuer.” This is wrong in two ways. First, this victim mentality is often deeply unhelpful for the trauma dumper because it establishes helplessness and passivity. Second, for Lisa, it forces her into a role she is unwilling and unequipped to take on; hence, “It makes me feel uncomfortable.”

Aristotle: What would the virtuous person do?

Some people will have read all that with a frown and an angry comment ready to go. “WTF? Not every conversation is seen in terms of hidden dynamics and power plays. Sometimes people just want help from their friends.”

Yes. I absolutely agree with my imaginary offended person. The issue then becomes what kind of friendship exists here. About 2,000 years ago, Aristotle argued that an essential part of this was having the right kind of friends. Aristotle divided friendship into three different types. Friends of pleasure are those who make us laugh and provide great company. Friends of utility exist for a shared purpose. And true, or good, friends are those who want the best for you.

The problem for Lisa stems from a disconnect in how she and her work friend view their friendship. Lisa thinks the friendship is one of utility — they’re colleagues and work friends, so they should probably leave their relationship at the door when they clock out. But her friend thinks there’s something more going on. So, it might be argued that Lisa is right to feel uncomfortable because this isn’t what she signed up for.

But there is more going on with Aristotle. For Aristotle, a good life is one full of virtue. Every moment is an opportunity for virtue. If Lisa abandons her trauma-dumping friend, what virtue does that demonstrate? It might be that it demonstrates kindness in the way Sartre and Karpman imagine it — she’s making her friend take responsibility. On the other hand, it looks a lot like betrayal, shaken and stirred with cold-hearted callousness. It’s hard to imagine a virtuous person abandoning someone who’s offloaded on you.

A wrong action does not make a wrongdoer

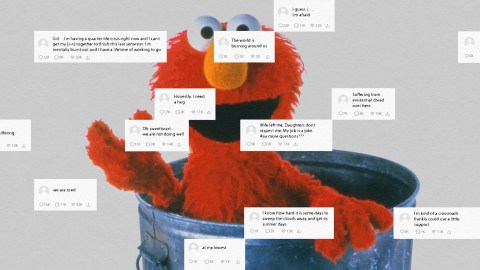

When I presented this question to people on social media, I gave three options: “Is trauma dumping right, wrong, or ‘other’?” The overwhelming consensus was “other.” Most people agreed that the ethics of trauma dumping depend on context.

First, it depends on what we mean by trauma. I have assumed that Lisa’s friend’s situation is about cheating boyfriends, irritating family members, or general life ennui. That’s not trauma. Trauma is about childhood abuse, rape, or prolonged suffering. In that case, an argument can be made that Lisa’s friend is wrong to force that on Lisa. But it can also be argued that Lisa is now obliged to take her friend’s trauma seriously, most likely by recommending she visit a professional.

Still, that is not how a lot of people use the expression “trauma dumping.” In modern discourse, trauma dumping is often treated as a kind of exaggerated oversharing that oversteps a boundary. And, as with any case of nonconsensual behavior, that’s wrong. Lisa doesn’t consent to the trauma dump but is forced to listen to it. That doesn’t mean Lisa’s friend is a wrongdoer. She likely misjudged their relationship and misread the nonverbal cues and tacit boundaries. So, my answer to Lisa is: Yes, the action is wrong, but your friend isn’t. You just need to establish boundaries.