Everyday Philosophy: Can we overcome alienation by becoming more assertive?

- Welcome to Everyday Philosophy, the column where I use insights from the history of philosophy to help you navigate the daily dilemmas of modern life.

- This week we dive into the lonely world of isolation, calling upon psychiatry and philosophy to help.

- Along the way, we consider the interplay of existential angst with feelings of exclusion from team sports.

I am a college student, and I am quite interested in playing volleyball with others. I am a beginner, so I always feel alienated while playing with them. The ball stays with hardly 4 or 5 players on the court, and the rest of us are just standing there, and I return to my room feeling underconfident. So, should I continue playing with them, or should I refrain from going to a place that makes me feel this way?

Yuvraj, India.

When I get sent a question, it can go one of two ways. Either I have to stew on the issue for a great while — dig out some books, find a silent corner of the house, and ruminate with all the exertion of Descartes in front of a candle. At other times, as with Yuvraj’s question, a word or an idea just jumps out at me. It grabs me and demands my attention like some chocolate-handed toddler heading for the sofa.

This week the word was “alienation.” That’s an interesting word to use. It’s a complicated emotion with a well-padded philosophical past. We’ve had a concept of something like alienation for a very long time; it was often associated with being alienated from God or your family. But philosophically, the idea really took flight with Georg Hegel (and then Karl Marx, but I’ll not use Marx this week to save my inbox from angry replies).

Yuvraj’s question states he was alienated by his exclusion. He was left out. He wanted to join in the volleyball game but was forced to be a spectator. Worse, he is denied any kind of cathartic and vocal grievance because he was ostensibly included — after all, he was allowed to play. But he felt excluded, which is a lonely, alienating state of mind. “What do you mean we left you out?” His team members can say, “You were on the court!”

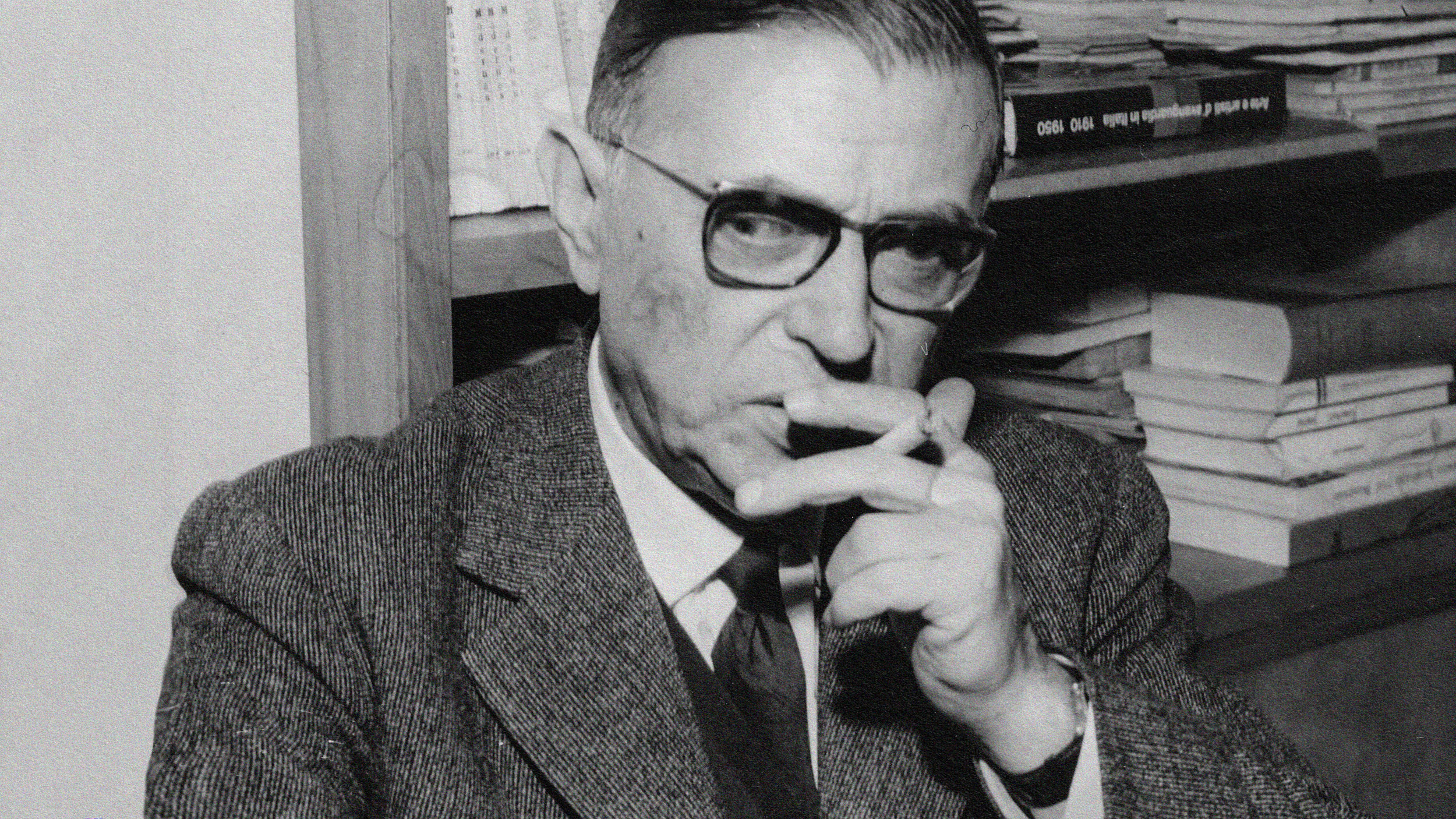

So, to help Yuvraj out, we’re going to look at two theories of alienation: those of the philosopher Albert Camus and the psychiatrist Harry Stack Sullivan. Along the way, we shall have to ask Yuvraj a deeper question: Why does he feel alienated?

Camus: Meaningful surrogates

When Friedrich Nietzsche proclaimed, “God is dead!” he was not claiming some heroic victory. Arguably, it wasn’t an evaluative claim at all, but a descriptive one — he was saying that God was no longer relevant in the same way as He had been for millennia. Today, we’re living in a God-sized hole. We’re wandering in a listless ennui, desperately trying to find something or someone to give us a purpose again.

When Camus wrote his philosophical essay The Myth of Sisyphus and novella The Stranger, he was taking on this Nietzschean baton. Camus argued that alienation comes naturally to us because we’re purpose-seeking creatures staring up at a cosmically uncaring universe. DNA, the fundamental forces, and orbital eccentricity are fascinating on an intellectual level, but they hardly nourish the soul. What purpose is there in a universe of atomic collisions and entropy? What meaning is there in our temporarily organic lives?

And so, we form communities, religions, and political institutions. We create evasions. A few hundred years before, Hegel argued that individuals can only realize themselves — becoming fully flourishing human beings — if they join in union with one another and the world. We need to be family members, team players, colleagues, and citizens. Camus, though, claims these are insufficient surrogates. They can hide the problem for only so long with only so much success. Eventually, we go home. We climb into our beds with our thoughts and ourselves for company. And then the great shadow of alienation and absurdity is waiting to pounce.

So, Yuvraj, take Camus’ point one of two ways. Either embrace the absurdity of your volleyball team — stick with them, and try harder to integrate yourself into the team. In the sweaty camaraderie of sport, alienation is forgotten. Or, you can stare at your alienation and try to come to terms with it. See the volleyball team as the surrogate or tool that you want it to be. If it’s not fulfilling its purpose — if it doesn’t dim your alienation — find something else to do the job.

Sullivan: the “one-genus” principle

From a philosophical point of view, Hegel argued that human nature is only satisfied when it forms a union with other human natures. Like some utopian Borg, we are happiest when we’re a collective; we’re fullest when we’re together. In some ways, Sullivan offers us a psychoanalytic version of Hegel’s point.

Sullivan argues that most of us have a sense of “normal” humans. We know what it is to be a human being, and a big part of that is to live in families, tribes, and societies. When we do something wrong or “sinful,” we feel as if we have failed our sense of being human. We feel unhuman. Sullivan argues that many patients with mental health conditions view themselves as “failed” human beings or somehow a species detached from everyone else. So, when Yuvraj fails to be part of his team, when he fails to play volleyball well, he feels not only like a bad volleyball player but a bad human. He has failed to integrate. He has failed to follow the “one-genus” imperative.

Our sense of self, or “self-concept,” as Sullivan put it, is essential to our well-being. People with a damaged or confused idea of who they are will be deeply and traumatically unhappy. If Yuvraj’s experience playing volleyball is eroding his sense of self and distancing himself from a sense of being a “good human,” then he ought to stop.

Overthinking a simple case

I often get grumpy if people say I’m “overthinking” an issue or when they say, “It’s simple.” I feel most things are never simple, and thinking rarely makes a thing worse. But, in this case, I hear the approaching, mocking voices. Is this really about alienation? Is this about the human condition and mysterious psychodynamic forces? Or is it actually just about the fact that Yuvraj isn’t very good at volleyball yet?

When we all learn something for the first time, there’s no way to avoid the embarrassing, fumbling virginal stages. We have to flounder and blunder along until we find our feet. Yuvraj isn’t “alienated,” he’s just embarrassed. He isn’t experiencing existential anguish; he’s just grumpy a skill hasn’t come quickly.

So, this is what I’d say: if, after a while, and when Yuvraj becomes better at volleyball, he still feels “alienated,” then stop. It’s damaging, according to Sullivan, and an inadequate surrogate, according to Camus. But, first, carry on and go back. Try a bit harder and a bit longer. I suspect something will change, and something will shift in how you feel. You’ll write back in a few weeks, telling me your volleyball team is wonderful. You love volleyball. Volleyball is the perfect balm for everyone’s existential anguish and psychoanalytic neuroses.