Daniel Kahneman’s transformative insights on rationality and happiness

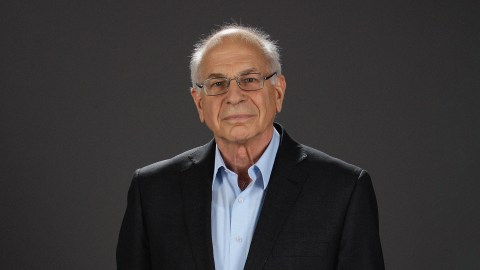

- Daniel Kahneman transformed the social sciences and established “cognitive biases” as a mainstream concept.

- Kahneman is often misunderstood, and his work is more subtle than people might assume. He does not believe humans are irrational.

- Less appreciated is Kahneman’s work on happiness. Here, we find wisdom that might transform our lives even more than his work on heuristics.

In 350 BCE, Aristotle wrote a book about the soul — or, more accurately, different types of souls. For Aristotle, a soul is what turns a lifeless lump of flesh into a walking, talking, singing, fighting, crying, and laughing thing. It’s what animates the inanimate, but it’s also what gets you out of bed in the morning. A soulless person is listless. A soulful person is full of beans. A soul is what drives all living things to carry on. But not all living things are in the same game.

Aristotle believed there were three “levels” of souls, each better than the last. The first, and least impressive, is the “nutritive soul” of plants. They eat, drink, and turn to the Sun. Impressive in the lifeless cosmos, but unimpressive compared to the rest of nature. The next best soul is the sensitive soul of animals. They feel and react. They make decisions, even if they are basic and determined by their biology. But the highest of all souls is that of humans. We have rationality, logic, and higher cognitive states.

Since at least Aristotle, humans have been defined according to their rationality — even our name, Homo sapiens, is derived from our ability to think intelligently. From Aristotle to Aquinas, through figures like Confucius, al-Farabi, and Dignāga, the celebration of human rationality has been a common thread among philosophers. In the European Enlightenment, reason-loving found its zenith with a strident humanism that veered close to Frankenstein-esque hubris at times. The triumph of human rationality seemed unstoppable.

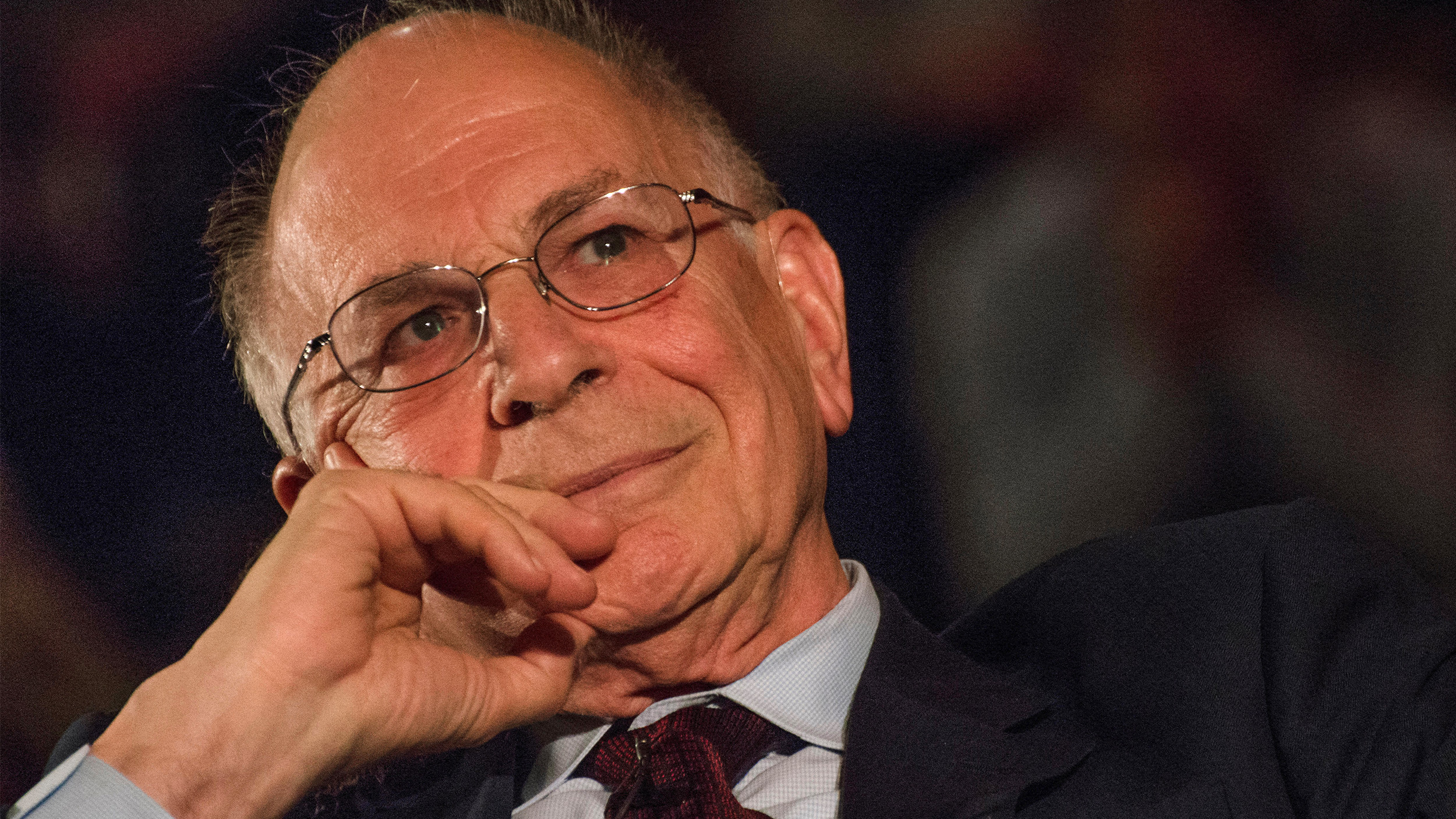

Then came the early 20th century. In response to the unprecedented violence and destruction of the two World Wars, we saw the rise of surrealism, Dadaism, and the Frankfurt School, all of which argued that rationality didn’t give us a utopia — it gave us Dachau. For the past century or so, rationalism has been limping. In 2011, it suffered another blow, this time from an unlikely source: a soft-spoken 77-year-old named Daniel Kahneman, an Israeli-American psychologist and economist.

Kahneman died on March 27, 2024. Here, Big Think takes stock of what Kahneman added to the world.

Homo intuitivus

Kahneman’s book Thinking, Fast and Slow has sold more than 10 million copies worldwide. It’s come to define pop psychology as a genre, and you probably can’t walk a mile without finding someone who’s read it or at least knows the gist of it. The book is a modern take on the “dual process theory” of human thought, which states that the human mind is defined by two separate but often related modes of cognition.

The first is rationality. Kahneman refers to this as “System 2” thinking, which we use far less frequently than “System 1.” System 1 thinking uses biases, heuristics (mental shortcuts), and intuitions to make decisions quickly and efficiently. It makes the kinds of snap decisions that help you navigate a fast-moving world, such as first impressions, gut feelings, and unconscious thoughts.

When System 1 goes unchecked, we’re liable to develop cognitive biases, an idea introduced by Kahneman and cognitive psychologist Amos Tversky. When you take shortcuts, you sometimes miss things. When you simplify, you reduce. A bias is an example when System 1 thinking prioritizes efficiency over accuracy. These days, you can’t go long without hearing about biases. We have the confirmation bias of social media echo chambers. The representative bias in racist criminal profiling. The anchoring bias of used-car salesmen. We are all now much more aware of how small a pocket rationality occupies in our broader cognition. We are not so much Homo sapiens, but rather Homo intuitivus — “intuitive man.”

But even though Kahneman’s work could be seen as challenging the Enlightenment’s fetishization of rationalism, his work never argued that “humans are not rational.” To Kahneman, it was partly a question of definition:

“I think the whole issue of whether people are rational or irrational depends on your definition of rationality,” Kahneman said in a 2009 interview with Lance Workman. “What you find is that there is a definition of rationality that is accepted in economics and if you stick to that definition then people are definitely not rational – it’s all about economic decision-making. Of course that does not mean that they are crazy, as this is quite different to what being rational means in everyday language.”

“One way out of this ‘why do we make bad decisions under some circumstances?’ debate is by introducing a dual-process model. This is based on work I did with Shane Frederick, and the model assumes that there are two ways in which decisions are produced. System 1 is very rapid, automatic, effortless, and intuitive. System 2 is slower, rule-governed, deliberate, and effortful. System 2 sometimes intervenes on behalf of System 1 as it ‘knows’ the latter is prone to violate certain rules. This means that we are likely to make errors when System 2 fails to correct System 1. That’s when we appear to act irrationally at times. We have a very rational system available – but it isn’t always engaged.”

One important note here is that these heuristics and biases are, in themselves, rational behaviors. Our brain has a huge computational task every second of the day. There’s a lot for it to do. In the evolutionary dawn of humankind, obsessing over trivia and taking minutes to decide a course of action would, at best, slow you down. At worst, you’d get eaten by a saber-toothed tiger. As in the primordial past, so today. Our brain uses these short-cut heuristics to allow us to take care of things that matter. A heuristic is, 99% of the time, a useful and essential part of our brain’s normal operations. But, in that 1%, a heuristic morphs into its shadow self: a bias. It makes us look decidedly irrational.

Kahneman and Aristotle

In many ways, what Kahneman was saying wasn’t that different from what Aristotle said in 350 BCE. Aristotle, in his treatise Rhetoric, argued that humans are not only swayed by rationality (logos) but also pathos (emotion) and ethos (various biases, especially the authority bias). Aristotle, again, not unlike Kahneman, argued that logos was the most powerful and convincing.

At the risk of straining the point, there’s also another important connection between ancient Greece and Princeton (where Kahneman was professor emeritus of psychology). Aristotle’s conception of happiness had very little time for hedonia, where happiness was confused with the kind of temporary state of bliss we get after eating ice cream. True happiness, or eudaimonia, is a state of being that comes from fulfilling your purpose. As Big Think noted in 2022, “For Aristotle, eudaimonia is a full or flourishing life. It might involve or accompany pleasure, but it doesn’t seek it… It is more of a visceral, intense state of being (more than a “feeling” even) that is both caused by and motivates doing things well. It is much harder to measure.”

Kahneman transformed the social sciences and brought psychology into the everyday. He showed how far an idea can change our collective unconscious and steer our conversations. But, for me, the greatest contributions Kahneman gave us are [his] views on happiness.

In 2023, Kahneman gave a lecture at Oxford University where he made a similar point. In the lecture, Kahneman made a distinction between “life satisfaction” and “emotional happiness.” He argued that most people equate happiness with “happy feelings” — this state of bliss, which Aristotle called hedonia. But most people are actually happiest when they’re succeeding in life.

“If you look at life satisfaction and what makes most people satisfied with their lives, [it] has a lot to do with people’s goals,” Kahneman told Big Think in 2011.

Aristotle said the same thing, but using philosophical language. Aristotle believed all living things — from nutritive plants to Einstein — are happiest when they’re fulfilling their telos (goal). Happiness is doing life well. As Kahneman put it: “Life satisfaction is what people actually want. That is, when people set goals for themselves and make long-term decisions… people want to have a good story for their lives.”

Kahneman transformed the social sciences and brought psychology into the everyday. He showed how far an idea can change our collective unconscious and steer our conversations. But, for me, the greatest contributions Kahneman gave us are these views on happiness. Happiness is not the temporary bliss of a hormonal spike based on contingent and variable environmental factors. It’s writing a good story. It’s about being successful in what we want to do. And, if that’s what happiness is, we have to conclude that Daniel Kahneman died a very happy man.