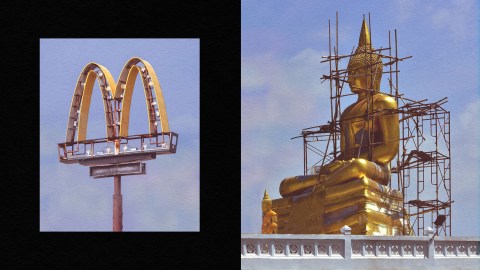

Beyond “McMindfulness”: How Buddhism actually eases suffering

- Commercialization of Buddhism overlooks the religion’s finer details.

- Buddhism isn’t about making suffering go away, but about confronting and embracing it.

- Its conception of selfhood is an antidote in an age of scientific positivism.

While working with Buddhist refugees in Nepal, medical anthropologist Adrie Kusserow met a monk who had fled torture in Tibet. You’d think that being driven from his ancestral homeland after nearly losing his life would have taken a toll on his mental well-being, but that didn’t seem to be the case. The monk said his mind and spirit had been protected by the principles of his life-denying faith.

“He described a resilient mind as one that doesn’t individualize suffering,” Kusserow tells Big Think, “claiming it as their own unique trauma narrative, but instead tries to be like the sky — liquid, spacious, humble, compassionate. Sems pa chen po,” a term from Tibetan Buddhism that refers to a vast or spacious mind.

Beyond “McMindfulness”

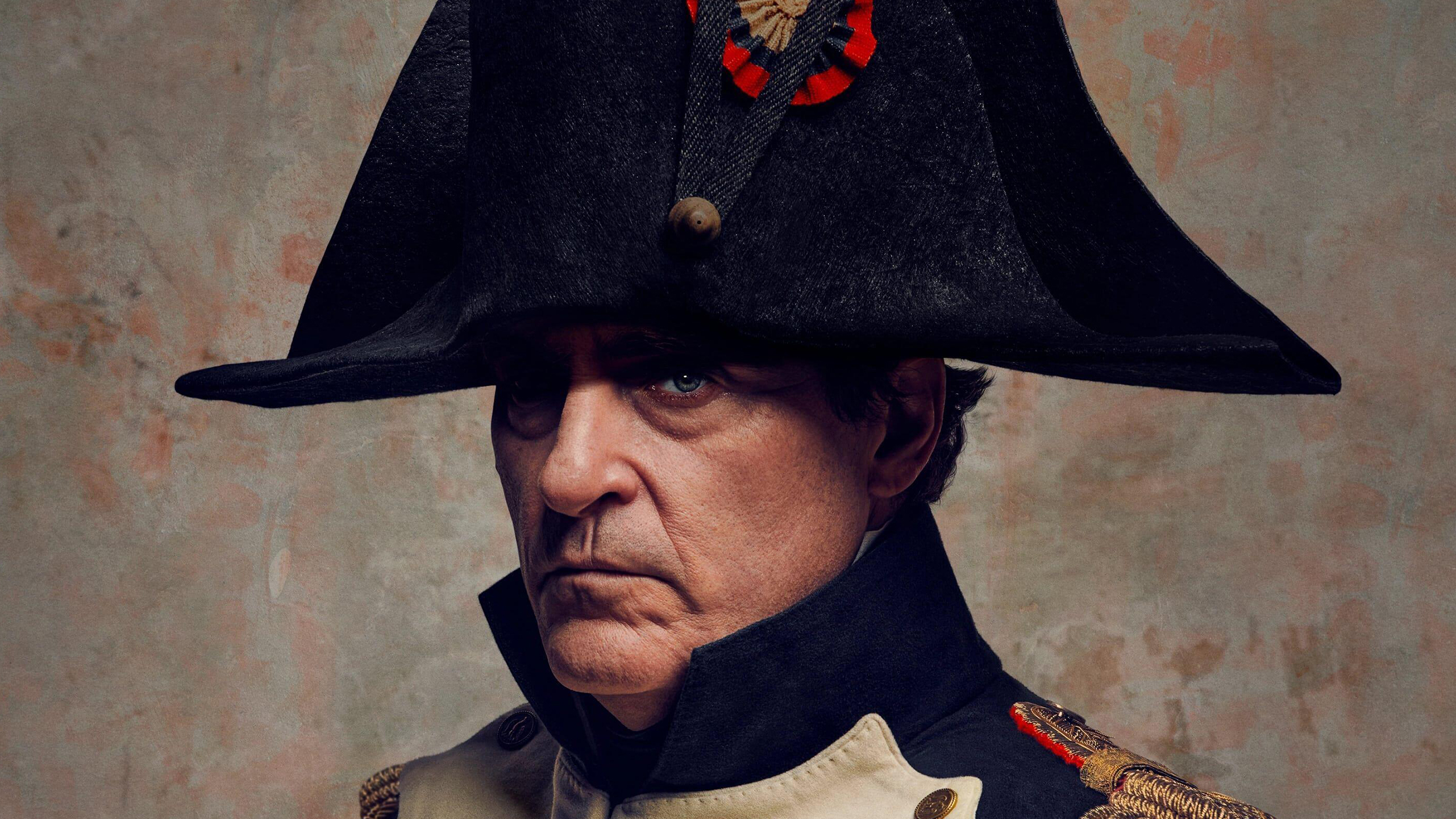

From soothing smartphone apps and Zen gardens to premium yoga classes and silent retreats, Buddhist ideas, practices, and aesthetics have become increasingly widespread in the Western world, thanks in large part to their promise of providing relief from the chaos and anxiety of modern life. But, as the writer Ronald Purser noted in his best-selling book McMindfulness: How Mindfulness Became the New Capitalist Spirituality, Buddhism’s contemporary commercialization — the global meditation industry alone is expected to bring in $31.9 billion by 2032 — bears little resemblance to the movement that originated in ancient India.

This is a shame because the latter — as indicated by Kusserow’s interactions with the Tibetan monk — can be much more effective at reducing suffering than the banal platitudes you find in self-help books loosely inspired by Buddhism.

Bees to honey

“I think it was a natural response to American upper-middle-class culture, which prizes psychologized individualism,” Kusserow, who teaches at St. Michaels College, told Big Think when asked what led her to study the anthropology of religion. “Buddhism encourages you to widen the self, to see it as interconnected, impermanent, it suggests everything is empty of any inherent sturdy, durable characteristics.”

Kusserow’s study of Buddhism and mental health has provided her with several tools to ease anxiety. One of these tools is shenpa, a concept in Tibetan Buddhism that encourages people to look critically at the thoughts and feelings anxiety elicits in them. Preached by Pema Chödrön, a student of the Tibetan teacher Chögyam Trungpa, Kusserow defines shenpa as “the quality of ‘getting hooked,’ of feeling like you need to itch and scratch your mental suffering with stories of doom, pessimistic predictions, etcetera.”

While meditating, Kusserow tries to make sense of her thoughts through metaphors. “Are they racing, sticky, like bees to honey, or oil jumping off a hot plate? This act of metaphorizing gives me further distance from them. I stand back and say, oh there go the bees again.”

The idea of inspecting one’s inner monologue shouldn’t sound all that unfamiliar to Westerners interested in Buddhism. But what’s left out of the McMindfulness, commercialized Buddhism playbook, which turns a profit by promising to eliminate individual suffering, is the realization that suffering is in fact inevitable: an omnipresent part of existence that can never be defeated, only overcome. Instead of seeking refuge from the cruelty of the world inside her head, Kusserow uses meditation as an opportunity to confront it in all its excess:

“I breathe in the dark, black, stifling suffering of all people in the world experiencing the same feeling and breathe out spaciousness, light, warmth to everyone, and this meditation helps me identify with the suffering of ALL humans and makes me feel less alone, less stigmatized, less isolated. So much of our mental angst comes from how we talk to ourselves about this suffering. Some Buddhists feel it is a way of paying off karmic debt, which gives the suffering a ‘purpose’ as opposed to ‘I have this horrible anxiety disorder and serotonin deficit which I am ashamed of and can’t really share or find wider meaning in.’”

Brook A. Ziporyn, a professor of ancient and medieval Chinese religion and philosophy at the University of Chicago, concurs, telling Big Think:

“What won me over [to Buddhism] was the eye-opening logic by which the embrace of the greatest fear, the very thing one wanted protection against and refuge from (impermanence, suffering, non-self), could be not only faced and embraced, but also, thereby, revealed to be the very protection and refuge originally sought. The embrace of the worst possible scenario turns out to be the only way to really overcome the fear of it, not only defanging it but positively transforming it.”

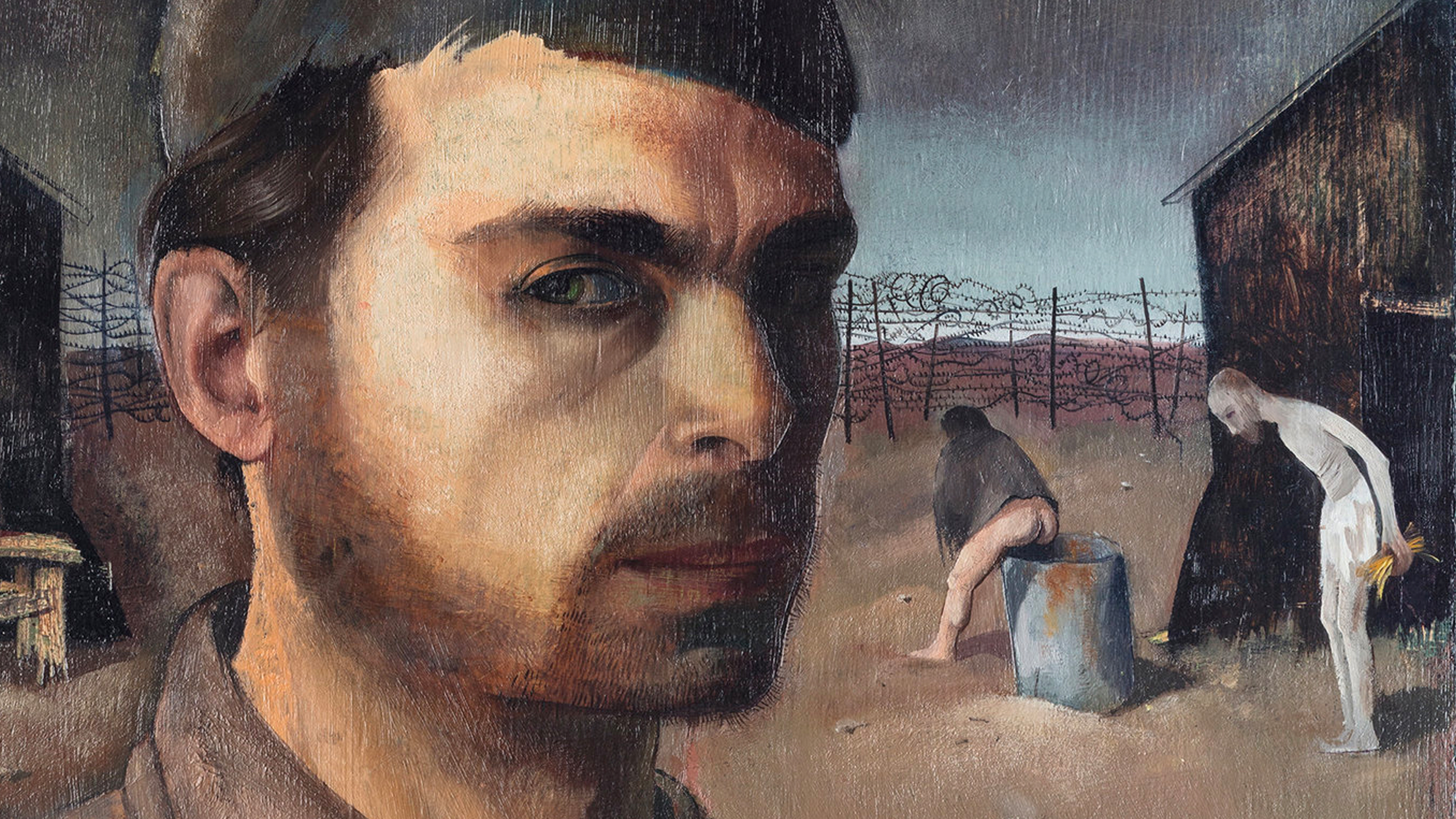

One way to embrace the world’s suffering is through reading literature and watching movies, which often follow people in undesirable circumstances. (Research on film therapy suggests it may be an effective treatment for anxiety disorders.) Utilizing her study of Buddhism, Kusserow reframed her own suffering after being diagnosed with cancer.

“When I went through breast cancer and then thyroid cancer, my chemo turned me into a dissolving, shedding, blistering, oozing being that lost her hair, bled from her gums, saw the skin on her fingers and toes start to peel, experienced a kind of cloudy chemo brain where I couldn’t hold onto thoughts as easily, and I continually thought of how Tibetan Buddhist prisoners of torture tried to reframe everything, including time in a cell to practice more meditation.

So, I viewed lying in bed as sort of like a retreat, my time to simply breathe, meditate, and truly viscerally experience the impermanence of the body that we all have, but are in a sense in denial about. Chemo brought me closer to the realization of the impermanence of the body than I ever experienced through my Buddhist intellectual studies. For that I am grateful.”

Buddhism and suffering

Kusserow’s is particularly interested in how traditional Buddhist attitudes towards suffering differ from their western, medical-scientific counterpart. “The concept of trauma as it currently exists in America isn’t something universal and has a definite historicity to it,” she says. “I suffered trauma when I was nine and my father was killed. My trauma was viewed in individualistic, biomedical terms, and I was prescribed talk therapy and medication that isolated me from sharing in the inevitable suffering that all humans go through.”

It wasn’t until she began studying Buddhism at Amherst College and, later, working with refugees in Nepal and India, that she was introduced to a different perspective, one she explores in a new memoir titled The Trauma Mantras: A Memoir in Prose Poetry. Although they had lived incredibly difficult lives, many of the refugees tended “to downplay negative emotions, striving to move beyond them and to not make a big deal out of them.” This was due, in part, to limitations of the Tibetan language, which — Kusserow explains — does not really have a word for “trauma,” but it also had to do with their religion:

“Buddhists see suffering not as an accident that happens to them but as a fundamental and unavoidable aspect of life. Trauma can’t be healed, because it will always be present; it has to be accepted, rather than treated. They also tend to view distress as a chance to cleanse negative karmic imprints and develop compassion for all others who are suffering. Hence, suffering is seen as somewhat contingent upon how the mind frames an event. Pending on how a person interprets negative events, like imprisonment or displacement, can cause more or less distress.

Rather than replacing scientific methods of dealing with trauma and suffering like cognitive behavioral therapy, whose utility has been tried and tested in numerous clinical studies, traditional Buddhism can be used to complement professional treatment, helping people heal themselves from within.