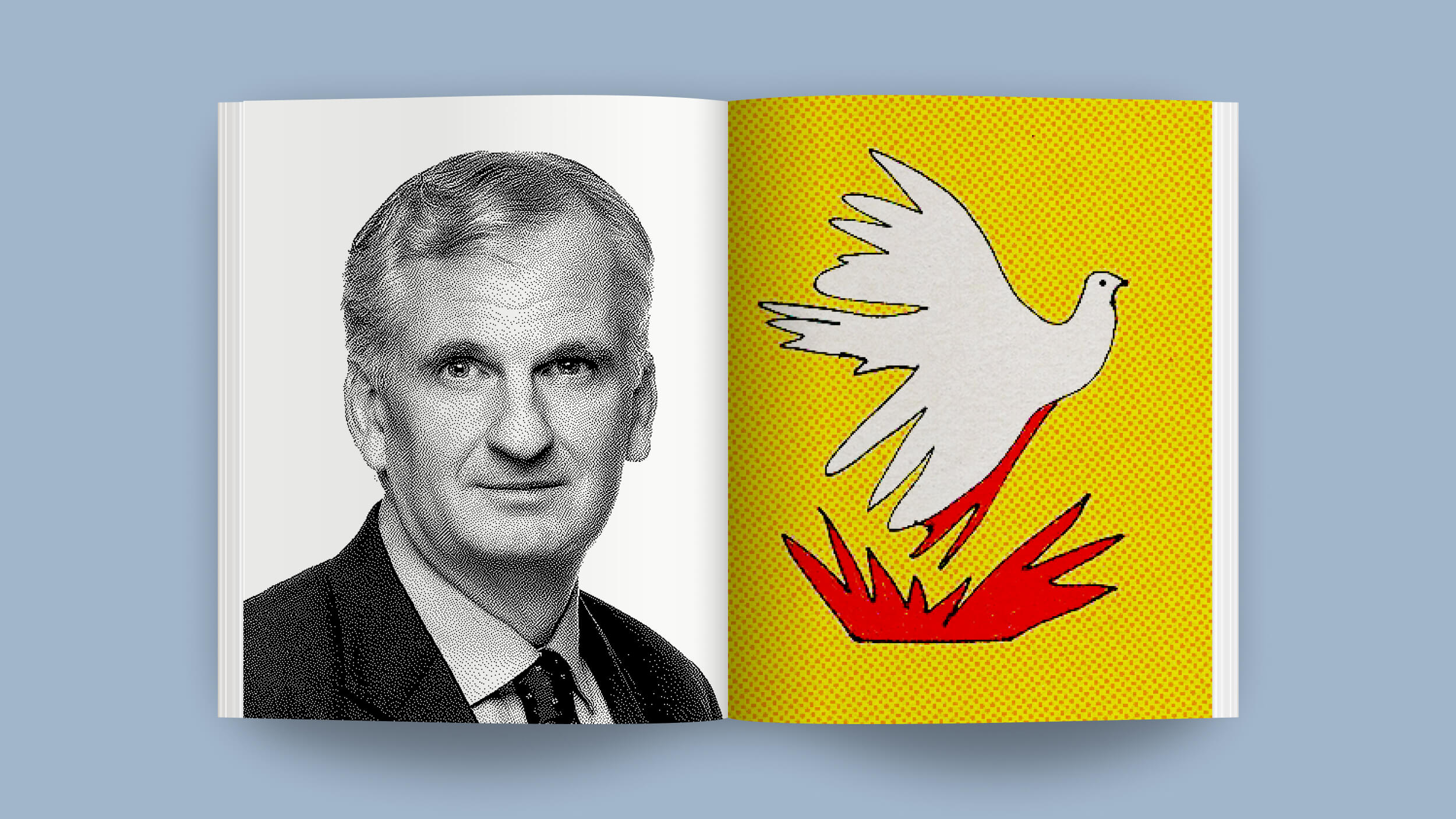

I don’t believe in blind idealism: An interview with Katarzyna Boni

ARUN SANKAR/AFP via Getty Images

Is it possible to bring a utopia to life? When searching for an ideal world, do we part with reality or maybe give it a new shape?

And is creating alternative realities something only cult leaders do? Stasia Budzisz discussed these and other questions with Katarzyna Boni, whose reportage Auroville: The City Made of Dreams was published in Polish in June 2020.

Stasia Budzisz: You came across one of the communities of Auroville, thecity of the future, by accident in 2009. You knew nothing about it, but what you found frightened you, and you decided to run away. What happened there?

Katarzyna Boni: I was travelling alone around the south of India. At some point, I felt that my journey made no sense; all I did was check the landmarks off a list from a travel guide. I figured it was the right moment to try some volunteering. I found a local community that planted trees and decided to join it. And so I ended up in Auroville, although the community was located on the outskirts rather than in the city itself. When choosing a project to volunteer on, I didn’t even know I was applying to an Aurovillian community – I just liked the idea of planting trees in exchange for food and shelter. I only learned about Auroville itself from my pocket guide. Two weeks in, I didn’t want to stay for a moment longer. I ran away to the Himalayas, at the exact opposite end of India. Several factors had prompted my reaction. First of all, I was at a stage of my life where I was changing jobs. I wasn’t yet in my thirties; I was still trying to give shape to my identity. I knew my dreams, but didn’t really know what to do with myself and what path to follow in order to get there. In the community, I met people whose situation was similar to mine, except they genuinely believed this place was going to save them. And I am severely allergic to this way of thinking, as I don’t believe in blind idealism. Back then, I saw Auroville as a settlement established by Americans and the French, convinced that communism was the best thing to happen to us because they forgot to ask Poles about the reality of it. I was cynical and mocking about Auroville.

You wrote that you wondered whether Auroville was a cult, and yet several years later, you went back there and wrote a book about a utopia. How did you come up with that idea?

The idea to write a book around this topic had been there for a long time; I even set up a whole separate project about it. But then I started working on a reportage in Japan – Ganbare! – and it consumed all my attention. I decided that my ‘utopias’ could wait and I shelved them for later. Then, just as Ganbare! was published, I got back on track with that topic. At first I thought I would write about various places that try to bring utopian ideas to life and are currently on different levels of realization. I was interested in the energy found at various stages of making a dream reality, how this energy changes over time, and how dreams and reality start to influence one another. At some point, I had a several-pages long list, including intentional communities and ideas for whole new nations (such as Liberland). I thought I would visit several places and then see what I might write. I wanted to visit South Korea, where a city of the future was created based on technology to facilitate every aspect of life. To me, Songdo is at the very beginning of its journey towards fulfilling this utopian dream. I wanted to visit Christiania which, as it seemed to me, was near the end of this road. I perceived Christiania as a ripe dream, if not overripe. I don’t know how much of it was true, since I never ended up visiting. Auroville was supposed to be the place to illustrate a dream in the process of being realized. I started with it, and once I took a good look at it from up close, I decided it deserved its own book. I think I made the right decision.

Why do you think that?

Auroville is one grand experiment. People came to the desert with their children and started establishing a new city, this new world from which a new kind of human was supposed to emerge. Auroville turned 50 in 2018, and I was curious about its children and who they grew up to be. What worked out, and what didn’t. I no longer needed other stages of utopias to describe what I found interesting.

Generating a new human species does sound a bit frightening and cult-like.

I had the same impression, which was why I ran away from Auroville the first time I was there. Once I returned, I knew I would have to face my reluctance. Indeed, some people there spoke in a very cult-like way. One of my interviewees said Auroville is inhabited by 12 clans that, in his opinion, provide a very natural way of distributing social roles within a community. There was a clan of priests, a clan of businesspeople, a clan of farmers. Still, Auroville is definitely not a cult. There is no initiation ceremony required for someone to stay there, even if they live there for a year, as I did. The trial period one has to undergo is a time you need to understand what the point is of working for this community. I recently spoke to an Aurovillian about how they’re handling the COVID pandemic. I asked whether the city helps the businesses (which are, in fact, owned by the city, since due to a governmental solution, Auroville is a foundation with an array of non-governmental organizations underneath. Were the taxes lowered, for example? My goodness, did she take an offence! “Kasia, what are you talking about? It’s Auroville that needs me now, not the other way round. Now more than ever.” I realized that, once again, I had missed the fundamental truth about Auroville: it’s the citizens who make the city, and they are not ‘made’ by it.

Auroville is not meant to provide a comfortable life; all it gives to its people is the means of basic survival, and everyone must take care of the rest. It is the citizens’ responsibility to make sure that Auroville – the idea in which they believe – survives. Therefore, the question Aurovillians ask themselves is “How can I support my community?” rather than “What can I get out of my community now?” It’s the complete opposite of the situation we are experiencing here, but I would not call it a cult. Those people have an idea that they believe in, and they understand it’s not possible to achieve it from the position of making demands. They have to roll up their sleeves and work for it. As for a new species of human, it all depends on how literally we read into this concept. Siri Aurobindo, an Indian philosopher from the University of Cambridge, whose thought served as the blueprint for Auroville, insisted that humans are not the final stage of evolution and that something else will appear after us. However, Aurobindo considered it from the perspective of consciousness rather than biology, as he believed we can still become better versions of ourselves. That’s how I see it. But in the 1970s, some people believed their children’s consciousness was already more advanced than everyone else’s. I’m pretty sure they were soon cured of that conviction. Today, nobody means a new species of human literally.

What image of Auroville did you have in your mind when you returned to this city to write a book about it?

I tried to keep my mind open, although I was going there with my own thesis. While my work on the book about Japan had taught me that such preconceived notions tend to go down quickly, I still need them for inspiration and ideas; they draw me into a new subject. The starting point was the dreams that shape reality. In Auroville, it’s perceptible. Before the humans arrived, there was nothing there, just emptiness. Dreams and reality were my first lead. Then, I wanted to see what they managed to achieve within those 50 years and what they did not; whether our society could learn from it, too.

In your book’s title, you refer to Auroville as The City Made of Dreams. Why did you choose dreams as the starting concept?

I wanted to write about a place in which one can see how dreams shape reality, and how reality shapes dreams, as well as see the moment in which the dream is no longer just that. It’s the moment when the reality has changed your goal so much, it’s no longer what it was when you were at the beginning of your journey. What to do then? Will you decide that you have changed along with your dream and want to keep going at it, despite it being different? Do you stick to it or leave it all and change your life again?

How much time did you spend in Auroville?

One year, not including my first time there in 2008, but it was not a year all in one go – I split it into several visits. Initially, I thought I’d make it three stays – two months long each time – but after my first visit, I already knew that was way too little time. The first visit allowed me to get into the community, but it was still just scratching the surface. I was only beginning to realize who was who and which issues I found interesting, but I didn’t even manage to conduct one interview. Not because the people of Auroville are wary of strangers or don’t want to talk to outsiders. They are simply very busy. Sometimes, they told me they could meet me in three months from now, which was why I needed more time. Aurovillians don’t have whole days at their disposal to spend talking to reporters and journalists, of whom many visit. The city saw a surge of journalists in 2018 when it was celebrating 50 years of existence. I was in a more comfortable situation, as I had arrived in Auroville a year before. It was a good time to start working on my project. Over the course of my first two months there, I realized the subject could fill the entire book. The next two months gave me my first interactions with the main characters of the story. That was when I decided to go back there for eight more months – also because I just wanted to experience normal life in Auroville. Did you know that in total, I spent four years working on this subject?

That’s a long time. You wrote that at some point, you thought about staying in Auroville for good.

If you live somewhere for a year and, due to the nature of your job, you try to get to know it in-depth, understand it, learn as much as possible about it, at some point, you get really drawn in. It’s natural to ask yourself whether you would like to stay there.

You had to dig deep into the memories of Aurovillians, but in your book, you point out that those who reach the community today are not focused on the city’s past. Where did you find documents on the history part of your book if they don’t teach the history of Auroville in their schools?

I did it bit by bit, in snippets. Of course, I looked for information in books about the first years of Auroville – in the Pioneer’s biographies and in my interviews with them. However, some things reached me as single sentences, dropped during my trips around Auroville, for example. This way, I learned about the conflict that divided the community in the 1970s, and I started researching it. If you keep asking, then sooner or later you will get some answers. But at first I didn’t even know myself what I was looking for. I grasped at various threads, arranged meetings and interviews, not knowing whether they’d take me anywhere at all. I often felt like I was stumbling in the dark. On the one hand, I knew what interested me and what questions to ask. On the other hand, I had no idea where it was going to lead me and what story I was going to tell. As if I was wandering around a labyrinth with many exits, each of them leading towards a completely different landscape. This experience was radically different from what I discovered when working on Ganbare!. In that book, it was obvious that I was writing about ways of handling trauma and loss. That was the core of my conversations and the people I chose to feature in that book. And here, everyone – not only an Aurovillian but someone just passing through Auroville as well – could be a potential character. The breakthrough came when I met Auroson, the first child of Auroville. He was the first aurochild and the first new human.

When exactly did you meet?

I found out about him during my second visit to Auroville. We made contact, but we did not meet at that time. In November 2017, when I came over for eight months, we were already in touch on a regular basis. We talked for many hours, and we became friends.

Who were your sources?

I divided them into two groups: those who could tell me their personal stories and those who could explain how Auroville handles the development of society. That is – how Aurovillians work on changing the system, how they look for solutions and which solutions have already been put to the test. When talking to the former, I wanted to know what made them come to Auroville. I also looked for people from both sides of the conflict that divided the community. I was very fortunate, since many of the Pioneers came back to celebrate the city’s 50th anniversary. Most of those interviews did not appear in the book since they were very similar and repetitive: arrival at the city, meeting the Mother, transformation, then life in the desert. As for the latter group, I wanted to know what Auroville does about various areas of life that it wants to improve, such as education, management, economy, architecture, culture, health and nutrition. I tried to meet with the people responsible for urban planning, with farmers, teachers, mediators, and with people who were brought up in Auroville since early childhood, at various stages of its existence. In order to draw in the children, I organized a creative writing class in one of the schools, but it was not very successful. Only one girl came back.

Congratulations!

Thank you. Discouraging people from writing is a very useful thing to do.

In your book, you admitted that you didn’t talk to everyone you wanted to interview. You didn’t find the courage to chat to Jurgen, even though you had spent several months waiting for him in a café. It’s a very honest admission for a reporter. Did you get cold feet?

I turned out to be a reporter who’s afraid of people. No, I did not speak to him. At that moment, it was more than I could have dealt with. It’s not like I was waiting there just for him. The ‘café’, or rather a tea-serving booth, was a place I had already frequented earlier, before someone said: “Oh, you must talk to Jurgen.” I started coming more often, Jurgen was never there, and when he finally showed up, I was taken by surprise, so instead of coming up to him and introducing myself, I just kept on drinking my tea. I was not in the mood for talking, and I found him a little intimidating, too. I could have always spoken with him later, after all. This happened several times. In the end, I found it embarrassing to start a conversation at that point. What would I even say? “You know what, Jurgen, I’ve been sitting here smiling at you, and it’s lovely to drink tea in silence together, but I’m actually a reporter and I’ve heard of you before. Could we talk about your life now?” I realized that I don’t have to come up to him. That not everything in my life has to revolve around doing research for my book. Sometimes, it’s good to let it go. I felt similar about a certain woman. I waited three months to talk to her, and then it turned out I couldn’t make conversation with her – she just frightened me.

Did you learn any other hard lessons while writing about Auroville?

It was difficult to decide whom I should describe and how to do it. I resolved not to write about my friends (whose stories were fascinating, and I would have loved to tell them, but I could not do it precisely because of our friendship). The relationship you establish with someone as a book interviewee is different than a relationship with a friend. This could also lead to a grudge; perhaps some of the things they shared were said in confidence granted by our friendship, and only some were meant for publication? It was also important for them to know whether I viewed them as friends or just book material. Auroson was the only exception to this rule, but our relationship was clear from the very beginning. Still, we became very close and sometimes I was not quite sure whether I was talking to him as a reporter or as a friend.

In Auroville, I came across one more difficulty that I didn’t have to deal with in Japan: here, many people simply refused to meet with me. In Japan, it was also easier for me to conduct the interviews, as they were all focused on just one topic. I arrived at a place wrecked by a tsunami, a place recovering from a trauma. Both I and the main characters of my book were clear on what we were going to discuss. In Auroville, it was much more difficult. I had to serve as a guide to a conversation whose topic was incredibly broad. I sought out turning points in a person’s life, something that made them chase their dreams, but I also looked for something that defined them, showed who they were, where they started and where they arrived. So I could have said: “Tell me all about your life, since your birth until now, and only then will I start asking you more detailed questions.” Of course, this was usually impossible. Therefore, the course of the interviews usually depended on how aware my interviewees were of the turning points of their lives.

In Japan, it was obvious that our conversations were all built around the events of 11th March 2011 and everything that came after. People exposed their emotions in front of me, but they did not have to look for some meta-level inside themselves that would allow them to view their lives from an observer’s perspective. My role is to facilitate entering that level with my questions. In Japan, I knew what questions to ask. In Auroville, I had no idea.

On top of that, the question about the meaning of our existence was always hanging right there in front of us, and that’s the most difficult question to handle, as it provokes banalities. Especially when writing a reportage on spirituality. There was one more problem at hand – I realized I find it easier to write about strong, painful emotions. They’re so overwhelming that they turn out to be enough to draw readers into the story. In Auroville, there is no drama. All we get is mundane day-to-day life. I had to problematize it and find a way of describing it so that it remained interesting and absorbing, despite its lack of emotional highs and lows.

Do you think Auroville’s existence makes sense today?

Yes and no. I think it depends on how we approach this city. After all, we don’t need Auroville to change the world or to work on becoming better versions of ourselves. It’s not like the world won’t survive without it. Auroville has no importance to the world. Seeing how India – and the world in general – has moved forwards, we must keep in mind that Auroville has become somewhat stagnant, especially when it comes to technology. Still, just because I lived there doesn’t mean I understand everything that happens there. I keep asking questions. I think that Auroville is not pointless, because there are people still coming there today, wanting to try the thing it has to offer. This way, they can take something out of it, other than various ecological solutions – for example, they can discover that they don’t need Auroville to change. But this city provides an impulse, teaching them to ask the right questions. In my opinion, Auroville shows that change, while being slow and difficult, is actually possible. It requires enormous open-mindedness, endurance and conviction. The fact that changes happen so slowly is less comforting; today, we need changes to take place much more swiftly. But perhaps it would happen faster if more people worked to make them come true?

So how is the 1968 utopia different from the 2018 utopia?

The premise remains the same, but it’s the concept that was successful, not the city itself. The final vision is so vague that everything can work out – there is no ultimate goal, no ideal you strive to achieve. All we get is a clue: creating a place of human unity. Of course, it was said in advance that the city would reach its peak once it housed 50,000 people. Next, we would have to set up more communities until they covered the entire globe. But this recipe provided no measures. You have to try and figure it out yourself to make it happen. Auroville is not an escape from reality, because here, everyone takes responsibility for their actions. Everything is clear from the very beginning. Even the omnipresent Mother had no rigid guidelines to follow.

What was your relationship with Mother?

I don’t want to say who Mother was. But it is thanks to her that Auroville exists at all today. She convinced UNESCO and 124 countries to support its conception. She was a charismatic woman, a woman who could change people’s lives with just one look. She kept on changing their lives even after she passed away – many Aurovillians insist they can still feel Mother looking after them. I didn’t manage to establish a relationship with Mother. It’s not like I didn’t try to. Today I think I respect her, although I did not like her at first. I had my doubts about her, precisely because I saw her as a cult guru. Even though she is no longer alive, everyone – even those who are not very religious – keep referring to her words. I found Mother unsettling. Perhaps it was because I had never met someone so charismatic, even though I know such people do exist. She could evoke genuinely extreme emotions in people. When telling me about their meetings with Mother, Aurovillians had tears in their eyes. And yet, I didn’t trust her, as I didn’t trust the whole narrative that grew around her. On top of it, she stared at me from the photographs almost everywhere I went. As if she actually was the Mother of the People. I felt invigilated. I saw no love in her gaze.

Sometimes, people who have met John Paul II say they experienced similar emotions.

Yes, I also thought of this comparison when I was thinking about other charismatic people I might know. I think that meetings with John Paul II evoked similar emotions: elation, understanding, forgiveness, acceptance, concern, tenderness, love. People who describe their experience of meeting a person they considered charismatic often report it in a very similar way. I did not feel comfortable around Mother, but I knew I could not write my book without her.

The structure of your book is very purposeful. From the very beginning, we don’t know what to expect and how the story will unfold. Was that your conscious writing choice when you started to put it all together?

No, it emerged during the writing process. I knew I wanted to write the story of a city through the stories of its people and that each of these stories had to push the city’s story forward. But I had no idea what the final form would be. It was the same with Ganbare! – I had two drafts ready before I understood how to make a book out of them. In this case, there were even more drafts to work on.

Your book ends with a brutal statement about what life is.

Perhaps I needed Auroville to understand that.

Parts of this interview have been edited and condensed for clarity and brevity.

Reprinted with permission of Przekrój. Read the original article.