Apocalypse philosophy: What science fiction teaches us about existence

- The best science fiction presents philosophical thought experiments that make us ask deep questions.

- Here, we look at a broad range of apocalyptic and post-apocalyptic scenarios and isolate four themes common to them.

- As it turns out, science fiction has a lot to teach us about existence.

The best kind of science fiction is philosophy. Yes, lasers and teleporters are cool, but science fiction asks big questions. It imagines alternate worlds and exaggerated scenarios. It presents you with “What would life be like” thought experiments. The Matrix is about knowledge and truth, and Star Trek asks how we should form a perfect society. Gattaca considers reproductive ethics, and Starship Troopers is about just war theory. Isaac Asimov‘s rules for robots are more important than ever. Science fiction, when it’s done well, stays in your head for a long time.

One of the most popular subgenres of science fiction features apocalyptic and post-apocalyptic worlds. The Walking Dead ran for 11 seasons, and The Hunger Games has four movies. World War Z sold 15 million copies worldwide, and Station Eleven has won numerous awards. Here, we examine the deeper, philosophical question behind common apocalyptic ideas.

Who do we save?

When Worlds Collide is about a cosmic catastrophe, and the people of Earth plan for their imminent extinction. A rogue star has been spotted, and it’s set to destroy our planet. Similar storylines are also found in Deep Impact, 2012, and The Mist. In each case, humanity is left with only enough resources to save a small portion of the entire race. Who, then, do we save?

According to Immanuel Kant, all rational agents have the same right to life and free choice as anyone else. No one is to be treated as a means to an end but as valuable in themselves. For Kant, then, a lottery system (as in Deep Impact) would likely be the best. For utilitarians, we should save the ones who will provide future humanity with the best outcomes: the doctors, engineers, and the most accomplished. In reality, the world is almost certainly Nietzschean. The Übermensch of our time — the generals and government officials — will be first on the spaceships. It’s not even a secret that if there were a nuclear war, it’s the politicians who would get first place in the vaults and bunkers.

How shall we rebuild society?

Post-apocalyptic fiction almost always features a portion of society rebuilding and reconstructing a world from the dusty and deserted remnants. The Walking Dead and Fallout feature pockets of very different gangs or tribes that reestablish drastically different communities. But one of the bestselling examples of this is The Stand, where post-apocalyptic America is divided into the goodies in Nebraska and the baddies in Las Vegas. These scenarios raise a powerful question: How would we build society if we could start from scratch? It’s something that would make a good podcast.

This echoes a well-known thought experiment from John Rawls known as the “original position.” Essentially, it asks us to imagine that you were transported to a new society, but you didn’t know at all what class, age, or sex you would be or how much wealth you would have. How would you engineer the structures and prejudices of that society to maximize your chances of being happy and fulfilled? What post-apocalyptic world would be fairest to everyone?

To what extent should we try to control nature?

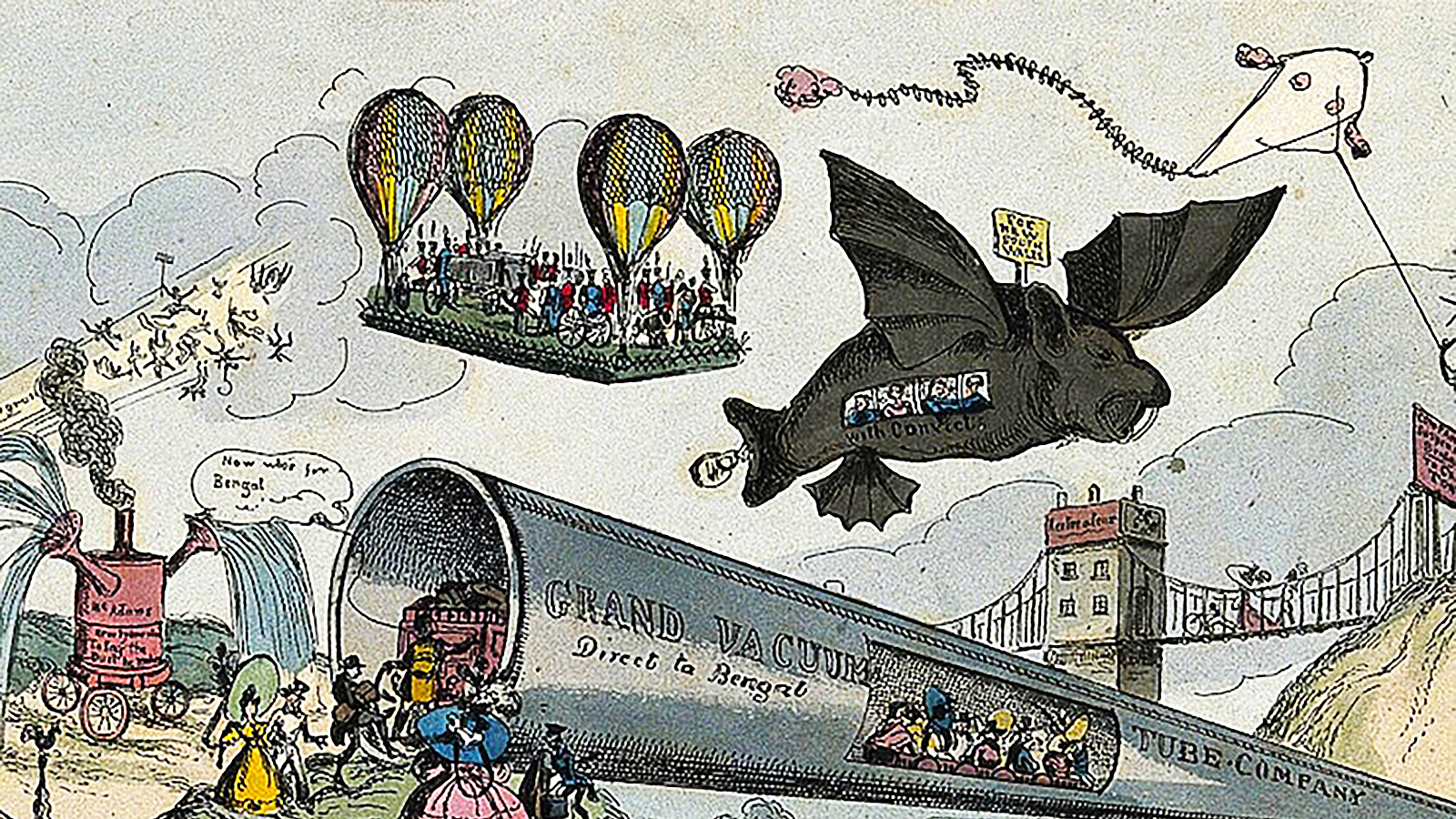

One of the defining characteristics of Homo sapiens’ success is our ability to control, tame, or push back against nature. We cut and burned down forests, we dammed rivers to stop floods, and we domesticated livestock. And yet, a lot of science fiction is based on scenarios where humans have gone too far, resulting in genetically engineered monstrosities or climate catastrophe. All of which raises the question: To what extent should we try to control nature?

It is naïve to assume we shouldn’t control nature at all. Antibiotics, air conditioning, and structural engineering all involve us manipulating the natural order of things. They involve killing and destroying. Francis Bacon and René Descartes saw controlling nature as essential to civilization. It was about the rational controlling the irrational; it was order from chaos. When the first humans cut down a clearing in the forest to build homes, this was no doubt true. But there comes a tipping point: a point when damaging nature also damages humanity. Apocalyptic fiction is a great tool to examine when and where that point comes.

What matters when you’re the last person alive?

28 Days Later opens with a lonely, confused man wandering the empty streets of London. Here is a man left alone in one of the busiest cities in the world. Oryx and Crake, I Am Legend, and Wall-E all feature characters fending for themselves in a barren, eerily silent world. They all raise an existentially important question: Does anything matter more than our relationships?

At first glance, a post-apocalyptic world seems pretty fun. No bosses, no queues, and no financial worries. You can drive the fastest cars, live in the biggest mansions, and binge on all the Dom Pérignon you want. But after that, what? What do you do?

One of the most powerful stories to explore this idea is Cormac McCarthy’s The Road. This features a father and son wandering a desolate, cold landscape. They’re not alone; there are bandits and horrors, but all that matters is the two of them and the love they have for each other. When the world is on fire, and there’s both everything and nothing to do, what matters most? It’s the people you love.

When real-life adventurer Christopher McCandless died alone in an abandoned bus in Alaska, his journal contained the line, “Happiness is only real when shared.” Without other people, what is the point of anything?