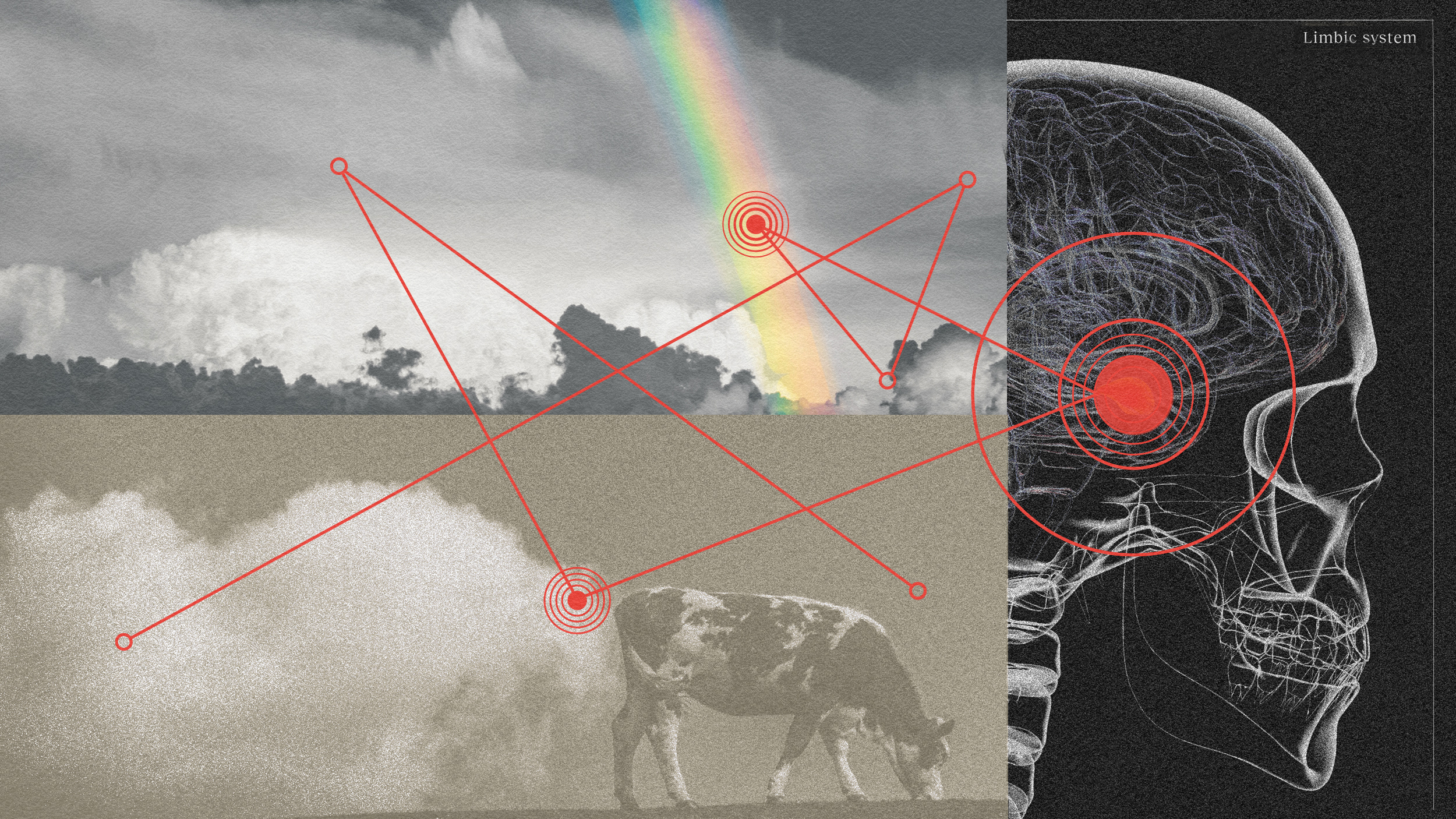

Why are we here? What is our purpose? Are any of our scientific efforts actually adding up to important revelations? Does understanding our cosmic origins really contribute to humanity as a whole?

We know what it’s like to be “street-level,” to understand our cities, our social behaviors, our day-to-day lives — but what happens if we look up? How does our understanding of humanity change when we raise our attention to the space beyond our skylines?

These are the questions that our host Kmele Foster is exploring in this episode of The Well podcast. Helping Kmele along the way is Sean Dougherty, the director of ALMA Observatory in Northern Chile, home of Earth’s darkest skies and 50% of the world’s megatelecopes.

If the answers to humanity’s questions are written in the stars, this observatory might be the one to translate them.

Dispatches the podcast, Episode 1:

The Atacama Plateau in Northern Chile. It's unlike any other place on Earth. The striking landscape is among the oldest and driest deserts in the world. And at an average elevation of 17,000 feet above sea level, it's also among the highest of high deserts. All of which kind of helps explain what I'm doing here. This desert is home to the clearest and darkest night skies on Earth. And since the 1960s, billions of dollars have transformed this region into the global capital of professional astronomy. Many of the largest, most powerful telescopes ever built are in operation right here. In fact, Chile is home to roughly 50% of the world's "mega telescopes." It's my second time here in the Atacama. And while I love stargazing, I'm definitely not an astronomer. But I am looking for something. It's the same something humans have been looking for in the stars for tens of thousands of years. Answers to the most fundamental questions we can ask about ourselves and the cosmos. Who are we? Why are we here? Do we matter? This season, we'll journey from observatories at the top of the world, to atom-smashing laboratories, exploring the tiniest building blocks of life, and everywhere in between. And because this isn't a conventional show about science, we'll be sitting down with a fascinating mix of people: philosophers, scientists, artists, musicians and beyond. And we'll talk about humanity's eternal search for meaning and purpose in our vast, miraculously complicated, rapidly expanding and incomparably mysterious cosmos.

- Let's go.

- For as long as I can remember, I've been obsessed with big questions. I suspect that's helped lead me to a career in media as a writer, a podcaster, and a commentator. But in recent years, I've grown increasingly obsessed with the biggest of big questions. How did I get here? Why is there a here at all? Look at this one. Look, it's twisted.

- Oh my gosh, how?

- I don't know. This probably has something to do with getting a little older and becoming a father, but some of this has always been there, creeping up on me in quiet moments. Here I am in a Universe that sprang into existence some 13 billion years ago. The birth and death of countless stars, galaxies emerging, colliding black holes. And at some point, our planet settles into a stable orbit around the Sun. And even after all that, there's still millions of years of evolution and happenstance before things finally arrive at me and you, here, in this fleeting moment we call the present. And somehow, despite being made of all the same stuff as everything else in the Universe, we're imbued with a conscious awareness of things. To paraphrase Carl Sagan, "We're that part of the universe that seeks to understand itself." I think you could see this both clearly in the natural and insatiable curiosity of children.

- You're gonna get rocks in your shoes. My daughter, Lia, manages to be fascinated by just about everything.

- Pretend that tree branches are the snakes.

- It's something I desperately hope that she holds onto as she grows older. And so modeling that lifelong curiosity that I hope to encourage in her, I decided to spend the next few months more seriously exploring some of these big questions. 'We choose to go to the moon, and we choose to do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard.' What I found is that talking about this kind of thing can be surprisingly difficult, even when you're talking with people who you know really, really well. Greetings and welcome back to another exciting installment of the "Fifth Column Podcast." Today, I was recording some interviews for this new show that I'm producing. It's about man's search for meaning and purpose in this possibly infinite but definitely very vast cosmos.

- So another small subject.

- Yeah, I mean, but I know this is a topic that's of interest to the two of you: science, physics, cosmology, astronomy.

- I'm pretty sure Moynihan said explicitly on an episode that we recorded recently that looking into space terrifies him.

- It actually scares me.

- I don't think looking at the stars is terrifying. I think it is awe-inspiring. And I would like for more people to be awe-inspired. But even more than all of that, I would actually like to try to figure out what we are here for, what I am here for.

- Really?

- I mean, look, there are plenty of ways that people have throughout history tried to connect themselves to the infinite, to get a better sense of what all of it means. In some cases, it's religious experimentation and devotion. In other cases, it is scientific investigation, and certainly, playing around with acid and drinking ayahuasca is part of that for some people as well. Look, I wanna sample all of the things and talk to all of the smartest people and try to get to the bottom of this mystery so I can perhaps get a slightly better sense of what it all means.

- So I don't get there through space. And I understand why that would be fascinating for someone who eats a lot of edibles. But like it's interesting that you're knitting that all together. So you're looking for the dinosaur in the Congo, and you're staring at the stars, and you're doing the ayahuasca all at once. It sounds to me like a classic midlife crisis.

- Yes, that is probably about right.

- What do you expect to get out of this? I mean, do you expect it to kind of sharpen the way that you think of politics, of life, of family, of consciousness in general? Or is there a goal that you're looking for that's going to change who you are and how you think about certain things in the here and now?

- I certainly hope that it will improve my person. It would be wonderful if I came out on the other side of this understanding myself better, perhaps having a better sense of what I want.

- Don't be one of those Instagram girls going on a journey with a fucking wide-brimmed hat on.

- Who knows? That may be where this ends.

- You look good though.

- There's no judgment there.

- Yeah.

- 12 hours of mediocre airplane movies later, my journey began. We are driving down very narrow neighborhood streets, many stray dogs afoot, and lots of potholes. That's a f****** dog in front of the car? Move, dog. Am I running over this dog? Oh, my God. I'm totally comfortable with this. This is all fine. So we have come to the Atacama Desert, and it's a high desert, which is why my ears are popping now to visit the ALMA Observatory. We're gonna go meet some of the researchers and scientists who are responsible for the work that they do at ALMA. And hopefully, we'll learn a little bit about not merely what ALMA does, but also so that we can get them off their scripts. I'm sure that they're gonna have a lot to say about why the work they do here is vital, but I don't have any doubts about that, what I'm interested in is what motivates people to get into this line of work at all. How do people who do this kind of work think about just the most fundamental questions about meaning and purpose? Speaking of which, we're actually here. We're at the gates of ALMA now. Fairly sure "PARE" means stop in Spanish. Kmele Foster. And we are free to proceed. Inside this unassuming hangar, a group of astronomers and dignitaries from around the world have gathered to celebrate ALMA's 10th anniversary.

- We built the world's largest ground-based telescope.

- It's a truly international effort. Chile provides the observation site, while funding is provided by a conglomerate of 21 countries, including the United States, Canada, Japan, Taiwan, Italy, Ireland, Austria, Belgium, United Kingdom- and I could read all the rest, but I'm not gonna do that here.

- In pursuit of the answers to our most fundamental questions: Where do we come from? What are our cosmic origins?

- Where do we come from? What are our cosmic origins? In the first 10 years, this state-of-the-art telescope has been uncovering mind-boggling secrets about the stars, planets, and the early Universe. You've probably seen that incredible image of the black hole at the center of our own galaxy. The sensitive instruments here at ALMA played a critical role in helping to capture that. One of ALMA's greatest achievements is its ability to capture breathtakingly detailed images of young stars, images that have revolutionized our understanding of how planets are born. More recently, ALMA detected complex carbon-based molecules 455 million light years away, meaning that the conditions that gave birth to our own planet are not unique in the vast expanse of the Universe. ALMA is rewriting the rules of our cosmic understanding, opening our eyes to a Universe teeming with wonders and possibilities. And we were lucky enough to get an opportunity to meet its director. Can I harass you for two seconds? Astrophysicist Sean Dougherty. This is kind of a big deal, culmination of a lot of effort.

- This is a really big deal.

- Yeah. Sean Dougherty grew up in West Yorkshire, U.K. It wasn't science but a love of climbing that first brought him across the Atlantic. In fact, if you'd like to know more about Alpine climbs and Canadian Rockies, he wrote a book about it. Sean ran Canada's national radio astronomy facility for 10 years before being appointed director of ALMA in 2018, where he's just signed on for another five-year term. And despite the fact that his father ran the local astronomy club, it wasn't the stars that initially brought Sean to the sciences. I wanna know about what made you first interested in astronomy. It wasn't until I was at university, and one of the math courses I took was astrophysics. But I didn't go into astrophysics at the time, so I actually did a master's degree in applied geophysics and signal processing. I thought that was gonna make my fortune and I was gonna retire in my 30s.

- Very practical goals.

- Yeah. But the first year of my job, I was away from home for more than 300 days of the year. And I went, "I cannot sustain this." And one day, I was musing, "What was it I really liked as an undergrad?" And I was thinking, 'I really liked astrophysics.' And that was the basis for me quitting what I was doing and going back to school to do a PhD in astrophysics. I just wanted something that was not related to making money. And it was as far removed from making money as you could possibly imagine.

- With respect to the connection that the average person has to astronomy, oftentimes, you'll have this profound discovery, like imaging the first black hole project- this was the event horizon telescope project, which ALMA was pretty critical to. Do you think the public has a real appreciation for the kind of work that you do and why it's important?

- One of the things that's really appealing about astronomy, about astrophysics is we produce these beautiful images of these most exotic objects in the Universe. And it's an easy way to create wonder in somebody, there's a lot of wow moments. Of course, the explanations for a lot of the phenomena are not easy, but that's not the essential bit. The essential part is astronomy is a real attractor to science in general. It's like an easy access, if you like, for people to better appreciate the world that they live in and the Universe that we are all in.

- I sometimes wonder if there is enough of a sense of thinking deeply about how all of this work connects to these deeper questions about why we're all here and what it all means. One can learn about the planets, but be sort of far removed from the reality of: "No you live on a rock in the solar system that is hurdling through space, this orbiting, this nuclear furnace. And it's one of billions and billions of nuclear furnaces that are in the sky." Like the mystery and the wonder of all of that, I'm struck by it all the time. And I don't know that I meet a lot of people who actually are.

- So you just answered your own question. You were so jazzed there about describing the Earth in the solar system, in the galaxy. I think, especially young people, they need to hear what you just described, a rock whizzing through the Universe.

- Yeah.

- I can say for myself, I mean, when I was teaching astronomy to city kids, and really get them to look up. Most people don't look up. You are walking around in the city, you look at this eye level.

- Or you're looking at your phone.

- Yeah, and even worse. And so we would take 'em out to the observatories as part of the astronomy course, and we show 'em the night sky out in the country. Watching the wonder that they had to look at the nearest galaxy, to our own galaxy, Andromeda- and Andromeda's 2.2 million light years away. And you then tell a kid that the photons that went in the back of your eye have been traveling for 2.2 million years. Loads of kids go, "Really? 2.2 million years?" What I really enjoyed was watching these young people suddenly realize there's a lot more to the world than down at street level. And that they really did live in this vast cosmos.

- So you have to go to medical to get checked out. Far above street level is where ALMA's 66 highly sensitive antennas live. And it was time for us to go take a look at it. But before our ascent further into the high Andes, I needed to pass a medical exam.

- Your heartbeat is normal, and your blood pressure, it's a little high, but it's normal, it's the first day in altitude.

- Okay.

- No problem. You can go to AOS.

- All right, thank you.

- Need you to pick up your oxygen.

- Yeah, yeah, okay. All right. Nicholas Lira is ALMA's education and public outreach coordinator. I have had a little shortness of breath. So I can only imagine what the average man is enduring at the moment. But it's definitely a little different. But the landscape is gorgeous. Apparently, there's a bunch of protected cacti here, and I believe that you would say cacti instead of cactuses. It's another thing about me. I am great about acknowledging my limitations. I have no problem saying, "I don't know." In just an hour and a half, we climbed 7,000 feet from the already quite elevated operation support facility to ALMA's high site on the Chajnantor plateau, 16,400 feet above sea level. For reference, that's about a thousand feet shy of Mount Everest base camp. Basically, it's really high.

- How are you, Dusty?

- How are you feeling?

- How are you?

- I'm feeling good.

- You're feeling good?

- Yeah.

- Okay.

- I mean, I feel the difference.

- Don't do like fast movements. Keep it slow. And we'll put the oxygen as soon as we get out of the building, okay?

- Okay.

- Apparently, this is one of the two highest buildings in the world. We are up above something like 40% of the Earth's atmosphere. All I know is I should take it very slow, because I feel like I could stumble over. Hopefully, when we get a little oxygen, I will stop slurring.

- Nico.

- Is it too low?

- Breathe. You really need to wear the oxygen once I go, okay?

- Get a little oxygen going here. Okay, just give me a second.

- That might be our take right there, like "Oh, this is getting to me. Oh, no wonder they do this. Geez."

- So at the most basic level, what is it we're trying to achieve here, in layman's terms?

- Human curiosity and science needs to answer some questions. Like where we come from. How is life formed? Where does life appear, okay? So we're trying to probe the coldest side of the Universe where stars are born, where planets are forming. We will also be able to see the chemical composition, okay?

- So we'll see there are just hydrogen, hydrogen and helium, or more complex molecule.

- We get to go up.

- So come with me.

- Okay. Okay.

- Hang tight, hang tight.

- Are you okay?

- Yeah, but we wanna let him catch it too.

- How is oxygen level?

- 05 or-

- No, actually, 1.

- 2, pull it 2.

- Pull it 2, yeah.

- All right, yeah, do me 2 too.

- Go ahead, yeah.

- So we're gonna show you the front end, the cryostat, okay?

- Oh, wow. It's like it's a little room. This is the part of ALMA's antennas that picks up faint signals from the farthest reaches of the Universe. Okay, perhaps not farthest, but pretty far. Each front end system is comprised of 10 receivers, and each of those detects a specific range of wavelengths. In order for the receivers to operate at the level of sensitivity required, they need to be kept cold, as in -450 degrees cold, so they live inside a giant liquid helium-based refrigerator called cryostat. At least that's what I've been told.

- That's amazing.

- Astronomy with superconductors on the top of a mountain in the middle of the world's oldest and darkest and driest desert. I think we were talking a little bit on the drive up here about some of the ancient cultures that have inhabited some of these same lands.

- Yes.

- I remember, I visited Peru a couple of years ago and visited Machu Picchu. And there's something that seems to run parallel in it. The sort of search for meaning and purpose.

- Well, Incas arrived to Chile in that time. So the Inca trails comes right nearby the ALMA site by the Likan-antai people, who are our neighbors, our host neighbors. This place is called the Chajnantor plateau. "Chajnantor" in Likan-antai means "the place where things take off." So they don't have big temples like the Inca did. But they did come here to observe the sky at the time. Likan-antai people will have different constellations that we know. They don't have Orion, they have the yacana, they have the fox, they have the animals.

- And are these the kind of reverse constellations?

- Exactly.

- So it's the dark parts of the sky.

- So they will use the shadows the shadows of the sky to name them instead of the bright points of the sky.

- Wow.

- The very places that ALMA observes too. We observe the cold sky, remember that, not the bright sky. So this is a really happy coincidence, I would say.

- You could go back a thousand years, and it's possible the only notable difference might be the technology. The Inca worshiped the stars, and their opposing dark constellations, because they believed everything was connected. Clearly, they were onto something, because today we know that the dark bodies representing animals are not just empty voids, but dense clouds of celestial dust. And it's these dense clouds that are of interest to ALMA, because it's there that planets and stars begin to form. And it's there that we may finally be able to understand how our own world came into being. But our Earth, as important as it is to us, is just one planet.

- The Universe is massive. Sorry, that's a really bad term. The Universe is very large. It also is massive, but not in the context of distance. And another way of appreciating the distance is there's a really famous photograph that Carl Sagan once described, a picture of the Earth taken from the Voyager satellite looking back towards the Earth, and this little pale blue dot.

- "This is where we live, on a blue dot. That's where everyone you know and everyone you ever heard of and every human being whoever lived lived out their lives. It's a very small stage in a great cosmic arena."

- That picture, to me, really conjures up just how, in the big scheme of things, how insignificant the Earth is. We'e just one planet around one star in a galaxy with a hundred billion other stars in a Universe with hundreds of billions of galaxies.

- On a personal level, I mean, how do you think about those distances that may not be traversable ever for humanity as a species? Does it matter that we may not ever be able to reach those distances?

- For me, personally, I don't think so. I mean, we live on this rock in our solar system. In roughly five billion years, we're gonna get eaten up by the Sun anyway, just as a natural part of the cycle of stars.

- Is that an important problem for us to solve in your estimation?

- I mean, we may solve it. But I'm quite content personally with the idea that I came from stardust, and I'm gonna end up stardust. It's perfectly fine with me.

- So what's the point of trying to understand what's out there if what we have here is kind of all will ever have tangible access to?

- No, okay. That's a really good question. And I think as humans, as curious humans particularly, the questions of where did we come from, what are our origins must be motivating, because that's fundamentally what we're trying to explore in astronomy. That's why we build telescopes like ALMA, to understand: where did atoms come from? How did we get to complex molecules? How did planets form out of the dust that came from the centers of stars? How did all this stuff, all the atoms in this building, if they came from stars originally, how did it come to be here?

- Yeah. So this morning, they are moving one of the large antenna up to the high site so that it can be placed into observation. They bring them back here behind the facility for upgrades and maintenance. And this one is ready to go. They've gotta decouple it from the platform. They've gotta lift it off of the ground, this massive structure. The process will take something like six or seven hours to move this up the hill to place it in a new position. It's kind of amazing to watch them maneuver this vehicle via remote control. All of the wheels can move independently. It was built especially for this purpose of transporting these massive antennas. I wanna ride inside of it. I don't wanna use the remote control. I wanna feel the power. I never really thought much about the physicality involved in astronomy. That's most basic: You just look up and out. But to obtain knowledge that's a little harder to access requires the design and construction of massive machines; the daily labor of hundreds of people working around the clock. And it's even occasionally dangerous. See?

- Hola.

- Hola, she says. This is my daughter.

- Nice to meet you.

- Hi.

- Yeah, it's coming up on the truck. This is massive. All right, that is massive too. Couldn't hear me, you mean? It probably has another hour or two til it gets up to the high site. We went ahead to the high site. And when we got there, it looked a little like Hoth. Weather's just another one of the extremes that the team here at ALMA has to deal with when carrying out their work. All of the dishes are in survival mode now, and they lock them down so that when there are high winds or anything else, they're not damaged in any way. Also, there's some snow accumulation in the dish and possibly, inside of some of the parts. So they'll come out, they'll inspect them all before they turn them back on and restart observations. This is my second trip to the high site. But the people who work here at ALMA are forever climbing this mountain. For them, getting to the top isn't the point. The point is to do the work that stands to change our perspectives, if we'll let it. What I wanna talk to you about now is the kind of existential stuff that I wrestle with and that I'm sure plenty of people wrestle with. I grew up in major cities. Didn't have a great view of the sky. In my adult life, I've actually traveled the world like looking for dark skies. I first came to the Atacama Desert in 2015 for my birthday. My wife brought me here, and we just spent hours looking through telescopes. And it was one of the most moving experiences like I've ever had. And I wonder, oftentimes if, for people who have a more intimate connection to the science than I do, if they perhaps derive something more from it, or if it becomes, it's just work, it's just kind of part of what you do. Where do you place the work that you do with respect to how you think about your own meaning and purpose, your own place in the vast cosmos?

- You guys are really pushing me tough here. I mean, I'm not a philosopher.

- That's okay.

- That's actually the answer that I want, in some respects. Like I'm not a philosopher. I don't know. Well, great. So where do you find meaning and purpose in your life?

- Yeah, that's a really interesting question.

- It's a very loaded question.

- No, no, no, I don't think it's loaded. I just think it's gonna be very different for everybody. And for scientists, especially for astronomers or physicists, the Universe revolves around a series of laws that can describe the Universe. But where did the Universe come from? Why did the Big Bang happen? Those are sorts of things that are quite challenging to address and are much more philosophical rather than necessarily explained by physical laws.

- Is it your suspicion that the science can't?

- Oh, no, no. I think the science is hunting to try and address those questions. But at some level, people say, "Well, you can't look outside the Universe," which is true, but what is it in? Are there multiverses? Those are relatively open questions, 'cause they're really hard to test. So you can't either prove them or deny them. And to me, that's where the philosophers come in. And the physicists who think about those more existential problems, good luck to you guys, 'cause I think, for me, it's really hard, that's really hard to grasp.

- Well, thank you for your time, and good luck with the next five years.

- Thank you.

- Meaning and purpose, awe and wonder, life and death. Starting up a conversation about any of these things can be hard, but once you get going, it can also be hard to stop.

- The thing that really grabbed me as a kid, remember the famous picture of the "Earthrise?"

- Yeah.

- To me, that really just blew me away.

- Yeah.

- When Armstrong landed on the Moon, I was nine years old. And I sat glued to a television five o'clock in the morning, thinking, "I can't believe there's a guy standing on the Moon," and then going outside and going, "There's the Moon. Holy smokes, we're standing on the Moon today." And as a young kid, that really appealed to me. Now, and I have no idea, years later, I got into mathematics and I got into physics, whether that Moon landing in 1969 was sort of that sort of seed that was set, planted really a long time and then was in the back of my brain somewhere.

- Kind of sounds like it.

- And then germinated, for some reason. I don't know, but I think the more important thing is asking the questions. You see a pebble in the stream. Where did it come from? How did it get there? Every time, the answer is just another a little piece in trying to understand the world you're living in. My kids are not scientists. But I'm sure happy that they ask their questions to me or their mother about, why is it this way?

- Yeah, yeah, very instructive.

- So whether you're an astronomer or you're an English lit major or a biology major, doesn't matter. Or an artist, doesn't matter. Just being curious about the world we live in, to me, that's the most important thing.

- Yeah. Sean was right. Curiosity is important. It is the engine of discovery and innovation. Looking up at the stars has always had a way of making us as a species ask the biggest questions, inspiring us to seek out answers. And naturally, that often leads to even more questions.

- I really wanna know how robots work. But why? Why did they wanna go to the Moon? Hearts are like Peter. How come we're the same and we think of the same thing? I wanna ask questions so I can know what the world's like.

- Yeah, me too. It's been a really cool trip. It's inspiring to know that people are enduring all of the sacrifices necessary to do all of this work. And I don't know, but I need more oxygen, 'cause I feel a little lightheaded and I'm losing my train of thought. In fact, at this moment, I'm not even sure what the show is called that we're producing. All I know is that trying to wrap your head around the vastness of the cosmos is enough to make your head spin, especially at this altitude. My wife says to be sure to take pictures. I'll take a selfie. It's a little embarrassing. I'll do it anyways. Wait, okay. That way. That's the way.