The Axial Age: With the birth of rational thinking, what happened to imagination?

- In ancient Greece, the Axial Age ushered in a new era of rational thought, giving rise to philosophy and eventually science.

- One of the pillars of scientific inquiry is measurement. For anything to be considered real and for any knowledge to be considered valid, it must be quantified and measured.

- However, this hyper-rational mindset has left humanity thirsting for something else. Man cannot live by measurement alone.

Around 500 BC — give or take a century on either side — a tremendous change took place in human consciousness, a shift so elemental that it marked a sudden break, in evolutionary terms, with what went before. This was the period that the 20th century German philosopher Karl Jaspers called “the Axial Age.” What happened then, Jaspers argued, is that around the globe, the major religious, spiritual, and ethical ideals — the “axioms” — that have informed Western and Eastern civilization first arose.

The Axial Age

It’s then in India that we find the Buddha. In China, there was Lao-Tse, the founder of Taoism, and his contemporary Confucius. In Persia there was Zoroaster, who first spoke of human life as a battle between good and evil, and in the Holy Land there were the Jewish prophets and patriarchs. That even in our skeptical age, the values embodied in these individuals still guide millions of people, suggest their durability, notwithstanding that they often receive more lip service than anything else.

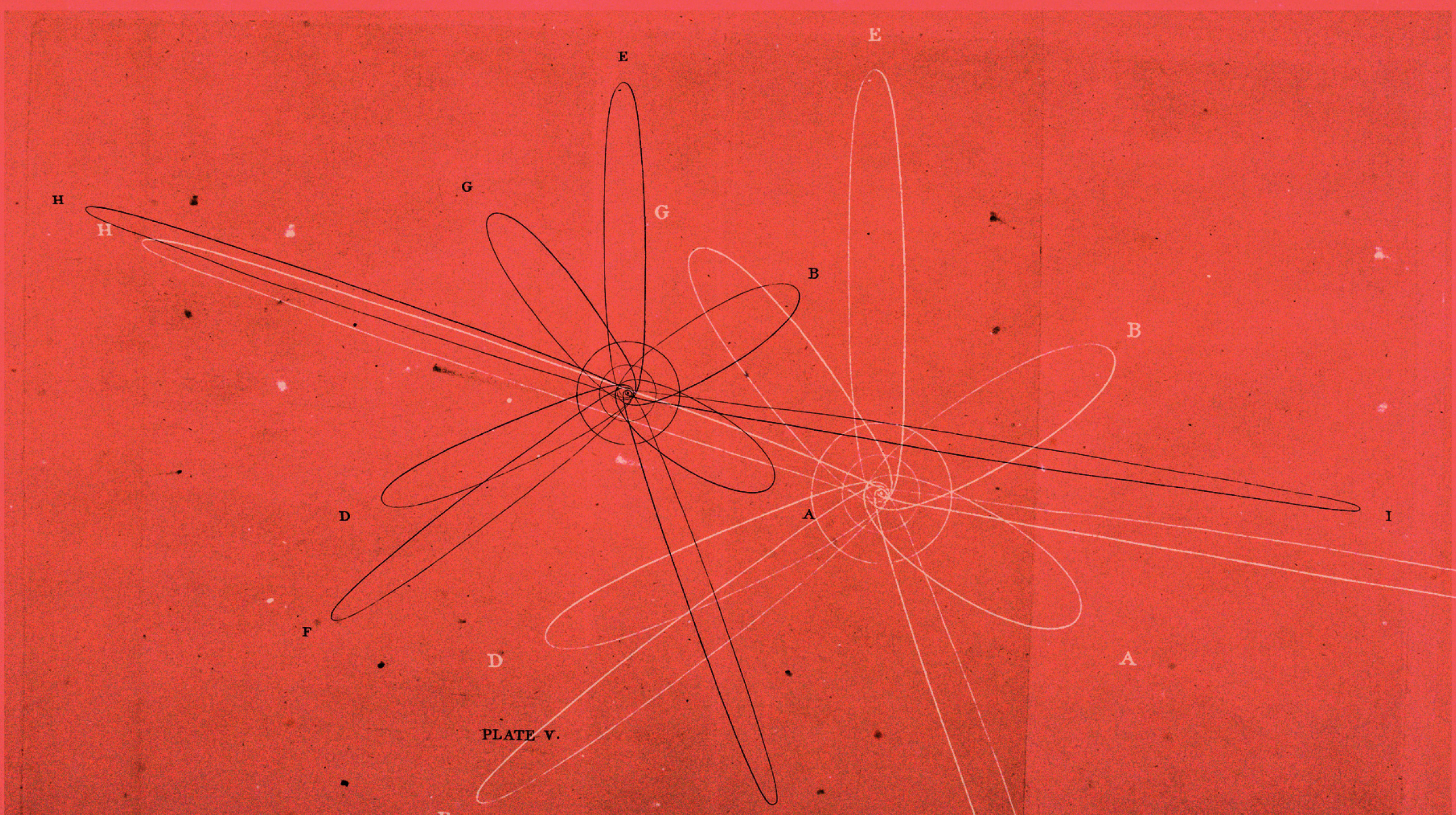

Yet in one location, the transformation that took place during the Axial Age was rather different. While in what we can broadly consider the East emerged religious and spiritual ideals, in the West, in the lands bordering the Mediterranean Sea, something else appeared. In Miletus, a once wealthy city in Ionia (in Asia Minor, what today we call Turkey), there appeared an individual who is generally considered to be the first philosopher, although the term “philosopher” wouldn’t be coined until a century after him. This was Thales, considered one of the Seven Sages of ancient Greece. With him the tradition of “rational inquiry” that we associate with the West began. Rather than accept the traditional mythological accounts of how the world came into existence, the stories of why the gods made it one way rather than another, Thales asked a simple question: What is the world made of? What is the basic “stuff” out of which everything else is made? As far as we know, no one before him asked this.

Thales believed the answer was water. Heraclitus, another early philosopher, believed it was fire. Anaximenes thought it was air. We may find these theories absurd. What is important is that in the West, what took place during the Axial Age was a shift from what we can call mythological, imaginative thinking, to rational, “scientific” thought. Although clocks had yet to be invented, the Western need to know “what makes things tick” had started.

Most histories of Western thought argue that with this shift, the earlier mythological, imaginative way of understanding the world died out. It didn’t. True, it was slowly and inexorably marginalized; yet this earlier, more intuitive way of understanding remained and is with us still, occupying a kind of shadow realm on the fringes of rational consciousness. It is what we call “the imagination.” Yet this is not imagination as we usually understand it, having to do with “make believe.” This imagination “makes real.”

Wait. An imagination that “makes real”? How could that be? Let’s see.

Mathematical vs. intuitive knowledge

Thales’ question proved powerfully fertile. Two millennia after he asked it, the method of rational inquiry he inaugurated laid the foundation for what we know as science. In the early 17th century, the new way of knowing crystallized into an approach of tremendous scope and success. It achieved the dominance it enjoys today through establishing rigorous criteria for anything to be considered knowledge or “real.” Among other things, these included quantification and measurement. For anything to be considered real and for any knowledge to be considered valid, it had to be quantified and measured. Anything not amenable to this was rejected. This qualification had enormous practical and utilitarian value. When applied to the physical world, it led to great predictive powers, and eventually, through technology, the mastery of nature. Thus began what is known as the “reign of quantity,” with us for some time now.

Yet, even at its start, there were some who knew that quantity’s reign came at a price. The mathematician, logician, and religious thinker Blaise Pascal was a prodigy. At age 12, he was sitting in on mathematics discussions with René Descartes, who, along with Isaac Newton, is considered one of the founding fathers of the modern measurable world. He devised an early calculating machine, the Pascaline, for his father, a tax collector.

But Pascal was also a deeply religious man. In his Pensées, the collection of notes left behind at his death, he makes the distinction between two different kinds of knowledge, what he calls the esprit géometrique and the esprit de finesse, the “spirit of geometry” and the “spirit of finesse,” or the mathematical and the intuitive mind. The difference between the two, is that while geometry works with exact definitions — such as that of a right-angle triangle — and proceeds step by step, the intuitive mind works with less definite but more meaningful sorts of things, the sorts of things that were the domain of our earlier, imaginative way of knowing, and arrives at its answers all at once. This is why Pascal could write that “the heart has reasons that reason does not know.” Reason does not know them, because the reasons of the heart can be felt, but not calculated.

Some centuries before Pascal, St. Thomas Aquinas made the same observation, distinguishing between the “active search” for knowledge, employing reason, and the “intuitive possession” of it. Throughout history, many others have come to similar conclusions.

The master key

The problem with this is that the intuitive mind cannot explain how it knows what it knows, in the way that a mathematician can walk us through an equation. Its knowledge arrives spontaneously, in a flash. The 20th century German writer Ernst Jünger spoke of what he called “the master key,” and distinguished between an understanding arrived at from the “circumference,” and one that starts from the “midpoint.” An approach from the circumference requires “ant-like industry,” the step-by-step plodding that gets us from A to B to C. But intuition takes us directly to the midpoint. It hits a bullseye every time. As Jünger says, it is like having the master key to all the rooms in a hotel: All doors are open to it.

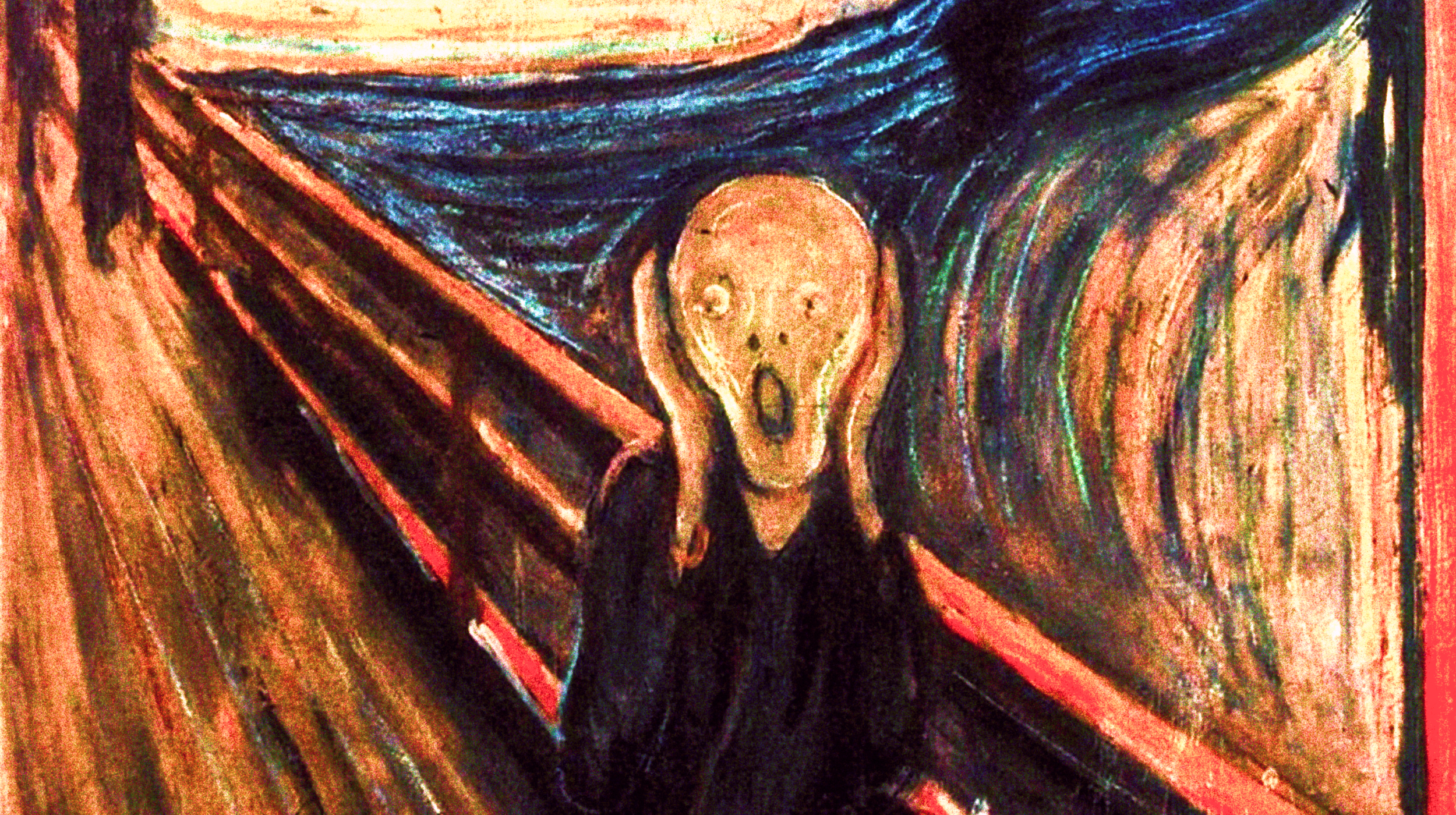

This is the central difference between these two ways of knowing. That of measurement remains at the surface, and it maps this with diligent, pedantic precision, but never reaches inside. The other way is slightly fuzzy, imprecise, and unrepeatable — at least on demand — but it penetrates deeper into the world, and reveals elements of it that the method of quantification cannot. These are the meanings that come through in poetry, music, art, and other forms of the imagination we acknowledge as something more than “make believe.” These are the “tacit,” “implicit” meanings that the philosopher Michael Polanyi said cannot be expressed “explicitly,” in the way that mathematical “meaning” can, but which are nevertheless felt. This is why the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein said that the truly meaningful things in the world cannot be said, but only shown. The explicit knowledge that enables our probes to reach into the unthinkable depths of space can tell us nothing about the awe we feel looking at a starry sky. But a poem or passage of music can give us some idea and even evoke a similar awe within us.

This is how imagination “makes real.” It “realizes” meanings that our explicit way of knowing cannot. This is why the writer J.B. Priestley once remarked that “truth can be obtained only at the expense of precision.”

Man does not live by measurement alone

We may think that the loss of this other way of knowing is a fair price to pay for all the advantages brought with the reign of quantity. Without doubt, we today live as kings of old could never dream of living. Yet as Pascal and others knew, we do not live by bread alone, however plentiful it may be. Physical nourishment is of course necessary, but other parts of our being must be nourished too. For all their undoubted mastery of the physical world, measurement and quantification can provide only bread.

They do this by reducing the complexity of the world to a “perfectly clear conceptual model of reality,” in the historian Francis Cornford’s words, that can explain all phenomena by the “simplest formula.” But this is achieved only at the loss of “all the value and significance of the world,” the exclusion of all that is imprecise, everything that cannot fit into the formula, which, generally, means everything that is meaningful to us. We can calculate the electromagnetic radiations making up a sunset, but there is no formula for why we find it beautiful. This is the contrast between what Cornford calls the “precise” and the “vague,” or what we have called the “explicit” and the “implicit,” which Cornford believed were “two permanent needs of human nature.”

We recognize the need for and value of the “precise” and “explicit” and have built a planetary civilization on them. The recognition that bread alone is not a healthy diet still seems sporadic, yet in my book Lost Knowledge of the Imagination, I look at how different individuals throughout Western history have recognized the need for bread and for that elusive something else that all the precision in the world cannot provide.

Since the rise of the reign of quantity, this elusive something else has increasingly been seen to be a mirage, and the appetite for the “vague” an unfortunate hangover from less rational times. And our means of embracing it, the “imagination,” has been reduced to the daydreams of romantics not able to face facts. This outlook may seem disheartening but it need not be so. Whatever pushed the mind out of its mythological mode and into our rational one may be at work today, preparing us for its next shift. There’s no reason to believe it cannot be one in which the two permanent needs of our nature enjoy an equal say.