Millions of medical devices using old code are open to attack, FDA says

Pixabay

- In July, the security firm Armis Security discovered network protocol bugs in a software component that supports many medical devices operating today.

- Now, the FDA and security researchers say that these vulnerabilities extend to more devices than initially thought.

- Fortunately, a large-scale attack seems impossible.

The Food and Drug Administration is warning hospitals and healthcare providers about decades-old cybersecurity vulnerabilities that could mean millions of medical devices are, and have for years been, open to attack.

In July, the security firm Armis Security discovered a suite of 11 network protocol bugs, named Urgent/11, within IPnet, a software component that supports network communications. These bugs could allow hackers to take control of certain medical devices and change their function, cause a denial of service, or cause information leaks or logical flaws that may prevent the device from functioning correctly, the FDA stated.

“Urgent/11 is serious as it enables attackers to take over devices with no user interaction required, and even bypass perimeter security devices such as firewalls and NAT solutions,” Armis researchers wrote in a blog post. “These devastating traits make these vulnerabilities ‘wormable,’ meaning they can be used to propagate malware into and within networks.”

This week, security researchers and government officials warned that these bugs aren’t limited to platforms running IPnet, but also other distinct platforms that have incorporated the same decades-old code.

“Though the IPnet software may no longer be supported by the original software vendor, some manufacturers have a license that allows them to continue to use it without support,” the FDA wrote in a statement. “Therefore, the software may be incorporated into other software applications, equipment, and systems which may be used in a variety of medical and industrial devices that are still in use today.”

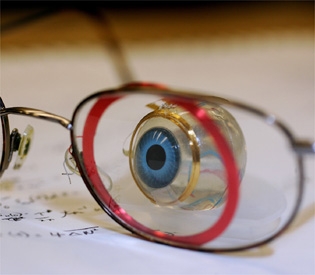

What kinds of devices might be vulnerable? Patient monitors, infusion pumps, cameras, printers, routers, Wi-Fi mesh access points, and a Panasonic doorbell camera, to name a few. But fortunately, a large-scale attack is likely impossible because, as a BD Alaris spokesperson told WIRED, hackers would need to target each device individually. Also, hackers wouldn’t be able to, for example, interrupt an in-process infusion.

Still, the discovery highlights a problem in the healthcare industry: most medical devices are hard to update, and don’t get updated unless a serious problem occurs.

“It’s a mess and it illustrates the problem of unmanaged embedded devices,” said Ben Seri, vice president of research at Armis. “The amount of code changes that have happened in these 15 years are enormous, but the vulnerabilities are the only thing that has remained the same. That’s the challenge.”

Some operating that might be affected include:

- VxWorks (by Wind River)

- Operating System Embedded (OSE; by ENEA)

- INTEGRITY (by Green Hills)

- ThreadX (by Microsoft)

- ITRON (by TRON Forum)

Armis released a free urgent11-detector tool that’s able to detect whether a system, on any operating system, is vulnerable to Urgent/11. The FDA also published a list of recommendations for health care providers, patients, and caregivers on its website.