When does the fetus become a “person”? The philosophy of gradualism provides a moral guide

I lost my twins in the second trimester of my first pregnancy. One fetus died around 14 weeks, and a month later I went into preterm labor – likely caused by the death of the first and an infection. I delivered the second twin, who appeared perfectly healthy on the ultrasound but was simply not old enough to survive, at 18½ weeks.

I grieved for years; these were some of my worst moments.

Ten years later, this experience is never far from my mind. But in the past few days since the U.S. Supreme Court’s overturning of Roe v. Wade, it’s also been a source of constant rumination. I think about the fact that the dilation and curettage, a common early abortion procedure I received to remove the placenta, is now banned when used to end a pregnancy involving a live fetus in almost all circumstances in six states. If my body had not ended the pregnancy, I wonder – would medical professionals have been too scared of prosecution to help me if the infection had worsened?

But mostly, I think about what the Supreme Court ruling of June 24, 2022, will mean for abortion in the second trimester. With early abortion banned or heavily restricted in much of the country, there will likely be a rise in second-trimester abortions, as several commentators have pointed out.

From my personal perspective, it is morally abhorrent to deny anyone the ability to access abortion in their own state, no matter why they are seeking one. But the likelihood of more abortions being pushed into the second trimester, as pregnant individuals must overcome more barriers to access, also matters from the point of view of moral concern about fetuses. Many people feel that losing a pregnancy after a few months is more tragic than an early loss. The same is true for later versus earlier abortion.

As a moral philosopher, I know that the philosophical theory of gradualism can help make sense of this idea. Gradualism insists that the development of moral status is a gradual process that occurs continuously throughout gestation. That means that later fetuses have more status than earlier ones; later abortions too are more grave morally.

Restrictions and delayed abortions

Most abortions in the U.S. tend to occur quite early: 79.3% at 9 weeks or earlier and 92.7% before 14 weeks. Compare that with 1974, just a year after the landmark decision in Roe v. Wade, when 21% of abortions took place in the second trimester.

Some second-trimester abortions are pursued because of fetal anomalies that are not discovered until later; in other cases the pregnant individual might want or need to end the pregnancy because of changes in their health or life circumstances.

Other factors leading to second-trimester abortions, however, are policy-based. Restrictions on public funding and mandated waiting periods can delay abortion care. Research shows that when states institute waiting periods of just 24 hours, the rate of second-trimester abortion increases for those relying on in-state providers. In 2015, Tennessee’s new waiting period led to a 22% to 43% increase in the second-trimester abortion rate.

Following the recent Supreme Court ruling, it is likely that delays will become the norm, since many pregnant individuals will have to travel hundreds of miles to the closest provider. Having seen surges of patients from Texas traveling to neighboring states, following the state’s adoption of a law banning abortion, clinics in blue states are preparing for influxes of out-of-state patients. Providers have also witnessed the later gestational age at which abortion is obtained by those affected by Texas’ ban.

Thus, even if pregnant individuals from the South and Midwest can eventually access abortion in another state, they might be forced to continue the pregnancy for weeks or months. Second-trimester procedures have more health risks than earlier terminations, they are more financially burdensome and there are fewer providers trained to offer them. Moreover, both providers and patients can find second-trimester abortion morally and emotionally difficult. In fact, 91% of those having an abortion procedure in the second trimester would have preferred to do so earlier.

What’s the moral status of a fetus?

The morality of abortion depends in part on the moral status of a fetus. Full moral status – sometimes called “personhood” – refers to having the same rights and deserving the same moral consideration as any other human being.

The most well-known views about the value of fetal life look for a specific moment or threshold of development at which a fetus achieves full moral status – what is known as a “bright line.” Most opponents of abortion tend to insist that conception is the bright line, while some abortion-rights supporters look to birth or the first breath.

In the Roe era, viability, the point at which a baby can survive outside of the womb, considered to be about 23 weeks, served as a legal bright line. Historically, “quickening,” when the pregnant individual feels fetal movement, at around four months or so, was thought to make all the moral difference.

In contrast to these bright lines, many philosophers look to cognitive capacities, such as consciousness, reasoning or self-awareness, which do not develop until the third trimester or even after birth. These views share in common the idea that before the bright line fetuses are of little to no moral concern.

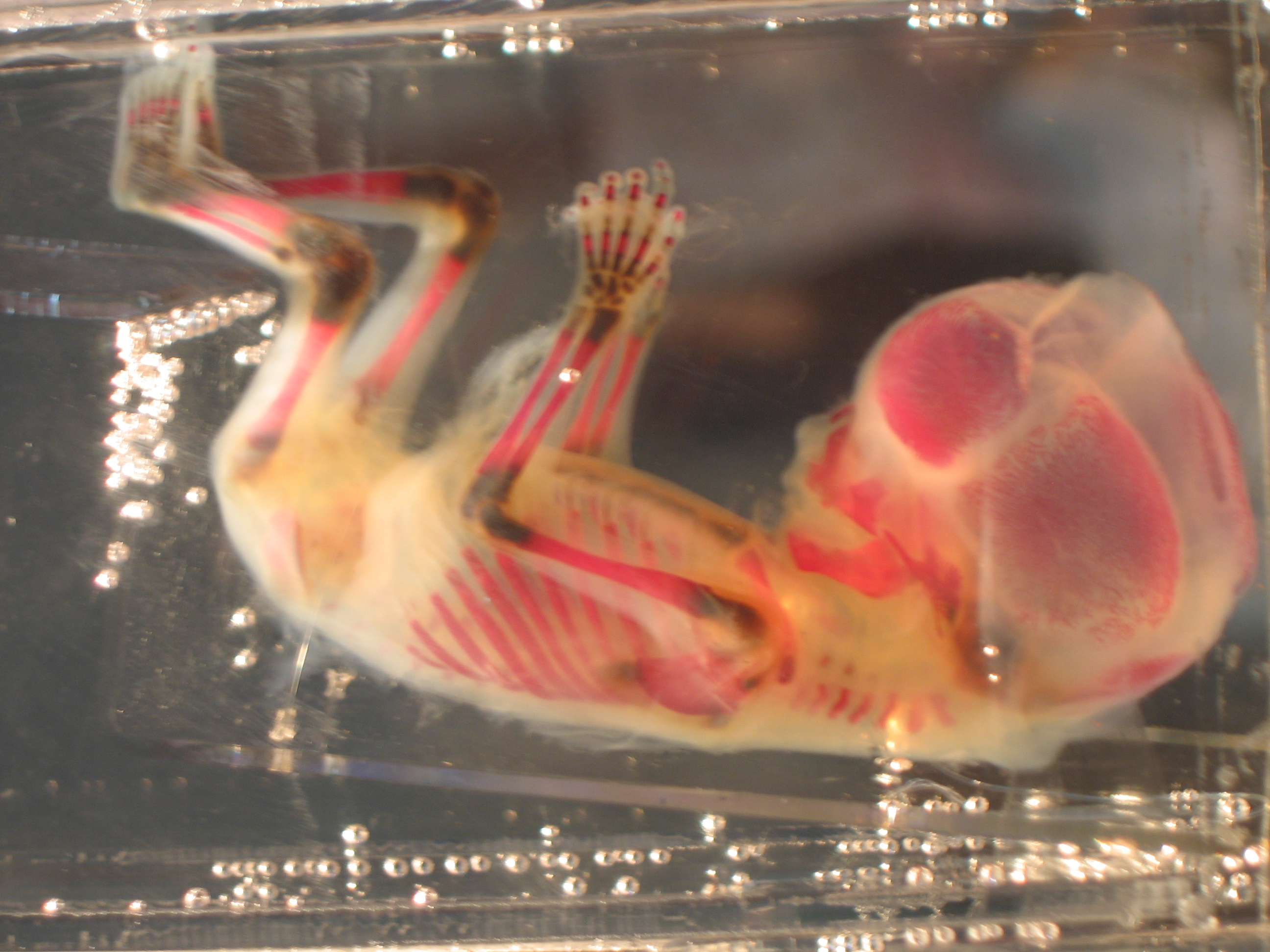

Gradualism rejects all of this. It holds that there is no such bright line. Instead, the development of moral status parallels the physical, cognitive and relational development of a fetus. Just after conception, a zygote has little more status than a sperm and egg. But as the embryo develops, its moral value increases slowly and steadily.

Thus, while a 6- or 8-week embryo might have very minimal status, a fetus at 32 or 35 weeks has virtually identical moral status to a newborn. Therefore, the earliest abortion is generally morally unconcerning to someone with a gradualist view, while third-trimester abortion is seen as a grave action that requires the strongest of moral reasons.

Meanwhile, midpregnancy fetuses are morally “in between,” as gradualist philosopher Margaret Little puts it. The idea is that by this point in pregnancy fetuses have not achieved full moral status, but they certainly have significant moral value – and ending their lives therefore requires moral justification.

Compared with the bright line views, gradualism has the benefit of making sense of the public’s strong support for early abortion, but hesitating about terminations in the second and third trimesters.

In the post-Roe era, the view also highlights the moral tragedy if state abortion bans targeting early abortion increase the number of second-trimester terminations. After all, from a gradualist view, early abortion is not seriously morally concerning, but second-trimester abortion is.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.