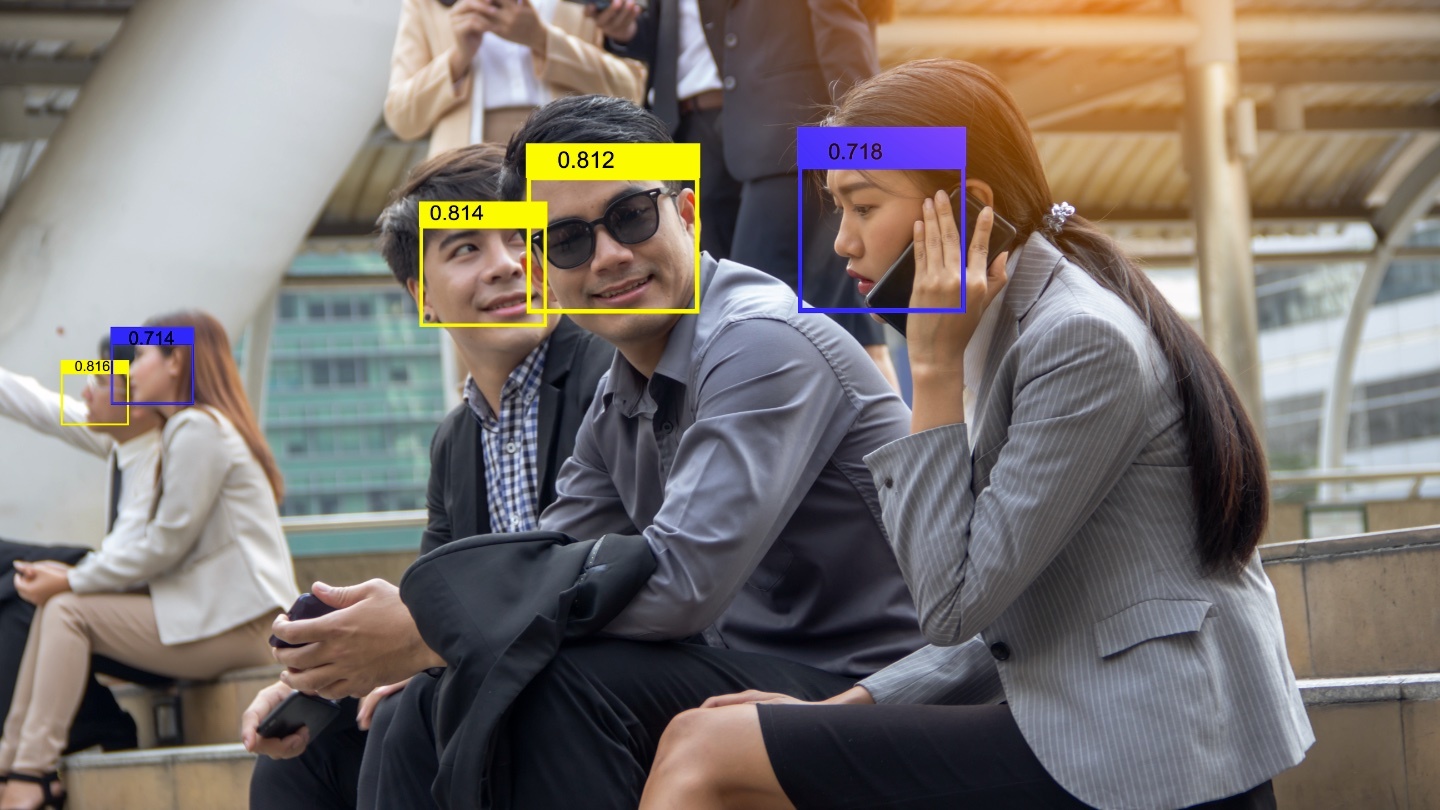

This company scraped social media to feed its AI facial recognition tool. Is that legal?

Image source: pathdoc/Shutterstock/Big Think

- Recent reporting has revealed the existence of a company that has probably scraped your personal data for its facial recognition database.

- Though social platforms forbid it, the company has nonetheless collected personal data from everywhere it can.

- The company’s claims of accuracy and popularity with law enforcement agencies is a bit murky.

Your face is all over the internet in images you and others have posted. Also lots of personal information. For those concerned about all those pictures being matched somehow with all that information, there’s some small comfort in public assertions by Google, Facebook, and other platforms that they won’t use your data for nefarious purposes. Of course, taking the word of companies whose business model depends of data-mining is a bit of a reach.

Meanwhile, as revealed recently by the New York Times, with further reporting from BuzzFeed News and WIRED, one company called Clearview AI has been quietly scraping up much of this data — the company claims it has a database of 3 billion images collected from everywhere they can. Their sources presumably include all sorts of online sources, as well as all social platforms including Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, YouTube, and so on. They even scrape Venmo, a particularly chilling revelation given the rigorous security one would expect a money-exchanging site to employ.

Combining their database with proprietary artificial intelligence, Clearview AI says it can identify a person from a picture nearly instantaneously, and are already selling their service to police departments for identifying criminals. You may think you own your face, but Clearview has probably already acquired it without your even knowing about it, much less granting them permission to do so.

Image source: Anton Watman/Shutterstock

In terms of Federal law protecting one’s personal data, the regulations are way behind today’s digital realities. The controlling legislation appears to be the anti-hacking Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA) enacted in 1984, well before the internet we know today. Prior to a Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals ruling last year, the law had been used to fight automated data-scraping. However, that ruling determined that this type of scraping doesn’t violate the CFAA.

Social media sites generally include anti-scraping stipulations in their user agreements, but these are hard — and perhaps impossible given programmers’ ingenuity — to enforce. Twitter, whose policies explicitly forbid automated scraping for the purposes of constructing a database, recently ordered Clearview AI to knock it off. Given last year’s CFAA ruling, though, sites have little legal recourse when their policies are violated. In any event, tech is a troublingly incestuous industry — for example, a Facebook board member, Peter Thiel, is one of Clearview AI’s primary investors, so how motivated would such people really be to block mining of their data?

Image source: Clearview AI, through Atlanta public-records request by New York Times

Clearview has taken pains to remain off the public’s radar, at least until the New York Times article appeared. Its co-founders long ago scrubbed their own social identities from the web, though one of them, Hoan Ton-That, has since reemerged online.

In efforts to remain publicly invisible while simultaneously courting law enforcement as customers for Clearview’s services, the company has been quietly publishing an array of targeted promotional materials (The Times, BuzzFeed, and WIRED have acquired a number of these materials via Freedom of Information requests and through private individuals). The ads make some extraordinary and questionable claims regarding Clearview’s accuracy, successes, and the number of law enforcement agencies with which it has contracts. Not least, of course, among questions about the company’s integrity must be their extensive scraping of data from sites whose user agreements forbid it.

According to Clearview, over 600 law enforcement parties have used their product in the last year, though the company won’t supply a list of them. There are a handful of confirmed clients, however, including the Indiana State Police. According to the department’s then-captain, the police were able to identify the perpetrator in a shooting case in just 20 minutes thanks to Clearview’s ability to find a video the man had posted of himself on social media. The department itself has officially declined to comment on the case for The New York Times. Police departments in Gainesville, Florida and Atlanta, Georgia are also among their confirmed customers.

Clearview has tried to impress potential customers with case histories that apparently aren’t true. For example, they sent an email to prospective clients with the title, “How a Terrorism Suspect Was Instantly Identified With Clearview,” describing how their software cracked a New York subway terrorism case. The NYPD says Clearview had nothing to do with it and that they used their own facial recognition system. Clearview even posted a video on Vimeo telling the story, which has since been removed. Clearview has also claimed several other successes that have been denied by the police departments involved.

There is skepticism regarding Clearview’s claims of accuracy, a critical concern given that in this context a false positive can send an innocent person to jail. Clare Garvie, of Georgetown University’s Center on Privacy and Technology, tells BuzzFeed, “We have no data to suggest this tool is accurate. The larger the database, the larger the risk of misidentification because of the doppelgänger effect. They’re talking about a massive database of random people they’ve found on the internet.”

Clearview has not submitted their results for independent verification, though a FAQ on their site claims that an “independent panel of experts rated Clearview 100% accurate across all demographic groups according to the ACLU’s facial recognition accuracy methodology.” In addition, the accuracy rating of facial recognition is usually derived from a combination of variables, including its ability to detect a face in an image, its correct-match rate, reject rate, non-match rate, and the false-match rate. As far as the FAQ claim, Garvie notes that “whenever a company just lists one accuracy metric, that is necessarily an incomplete view of the accuracy of their system.”

Image source: Andre_Popov/Shutterstock

It may or may not be that Clearview is doing what they claim to be doing, and that their technology is really accurate and seeing increasing use by police departments. Regardless, there can be little doubt that the company and likely others are working toward the goal of making reliable facial recognition available to law enforcement and other government agencies (Clearview also reportedly pitches its product to private detectives).

This has many people concerned, as it represents a major blow to personal privacy. A bipartisan effort in the U.S. Senate has seemingly failed. In November 2019, Democrats introduced their own privacy bill of rights in the Consumer Online Privacy Rights Act (COPRA) while Republicans introduced their United States Consumer Data Privacy Act of 2019 (CDPA). States have also enacted or are in the process of considering new privacy legislation. Preserving personal privacy without unnecessarily constraining acceptable uses of data collection is complicated, and the law is likely to continue lagging behind technological reality.

In any event, the exposure of Clearview AI’s system is pretty chilling, setting off alarms for anyone hoping to hold onto what’s left of their personal privacy, at least for as long as it’s possible to do so.

UPDATE: The ACLU announced on Thursday that it is suing Clearview in the state of Illinois. CNET reports that Illinois is the only state with a biometric privacy law, the Biometric Information Privacy Act, which requires “informed written consent” before companies can use someone’s biometrics. “Clearview’s practices are exactly the threat to privacy that the legislature intended to address, and demonstrate why states across the country should adopt legal protections like the ones in Illinois,” the ACLU said in a statement.

For more on the suit, head over to the ACLU website.