How the Electoral College sidesteps the popular vote

- By tradition, U.S. Electoral College electors vote for the presidential candidate who won the popular vote in their state.

- However, five times in U.S. history, the Electoral College has granted victory to the candidate who lost the popular vote.

- In Why We Vote, Owen Fiss, Sterling Professor of Law at Yale University, explores the consequences that can arise when there’s a discrepancy between the popular vote and the cumulative vote in the Electoral College.

The Senate is the Senate and as such should be viewed as a democratic anomaly. Yet the Electoral College, also established by the Constitution in 1787, extends the representational structure of the Senate — two votes for each state — to the election of the President and Vice President.

In the Electoral College, each state is given the number of votes equal to the sum of its representatives in both the House of Representatives and the Senate. As a result, although on Election Day Americans vote for the President and Vice President, that expression of the popular will is filtered through the structure of the Electoral College. As a formal matter, victory goes to the candidates who have the most votes in the Electoral College.

This threat to the democratic ideal is tempered by a practice — let us call it a constitutional practice — that has evolved over the last two and a half centuries and now prevails in all fifty states. According to this practice, rooted either in statutory enactments or informal social understanding, the members of the Electoral College are required to cast their vote in accordance with the popular vote in their state.

A risk remains, nevertheless, that because of the way the votes in the Electoral College are allocated, state by state, there may be a discrepancy between the popular vote, when viewed on a national level, and the cumulative vote in the Electoral College. As a result, a candidate who has the most votes in the Electoral College may not have won the popular vote aggregated on a national level.

On rare occasions, that risk has materialized, as it did in recent memory in the presidential elections of 2000 and 2016. In those elections, the candidates who had won the Electoral College vote and thus the presidency in fact lost the national popular vote. Accordingly, awarding victory in those elections to the candidates who won the most votes in the Electoral College betrayed the democratic ideal. From the perspective of our constitutional tradition, these elections must be regarded from the democratic perspective as aberrations, as malfunctions of the system, though the nation reluctantly acquiesced to the result dictated by the Electoral College.

The risk of such malfunctions would be greater if the electors were freed from the state laws and social understanding that tether them to the popular vote in the state they represent and were somehow allowed to exercise independent judgment as to who should become President and Vice President. Yet the Supreme Court, in recognition of the democratic ideal and the constitutional practice to which it has given rise, has consistently refused to grant electors this independence. Indeed, as recently as June 2020, the Court allowed the state of Washington to punish — by the imposition of a so-called civil fine of one thousand dollars — any elector who claimed for himself or herself this independence.

In this particular case, Justice Elena Kagan, who wrote for the Court, made it abundantly clear that the ruling was predicated not on a deference to the states as a tribute to their sovereignty, but rather on a desire to further the democratic aspiration of the Constitution. She described electors as nothing more than “agents of others” and characterized the state rule requiring electors to follow the popular vote in the state as a way of denying electors the power to reverse “the vote of millions of its citizens.” Referring to the common practice requiring the electors to honor the popular vote in the state, Justice Kagan, speaking on behalf of a remarkably unanimous Court, concluded: “That direction accords with the Constitution — as well as with the trust of a nation in that here, We the People rule.” In a related case, the Court upheld the power of Colorado to replace an elector who threatened to cast a ballot for a candidate who did not win the popular vote.

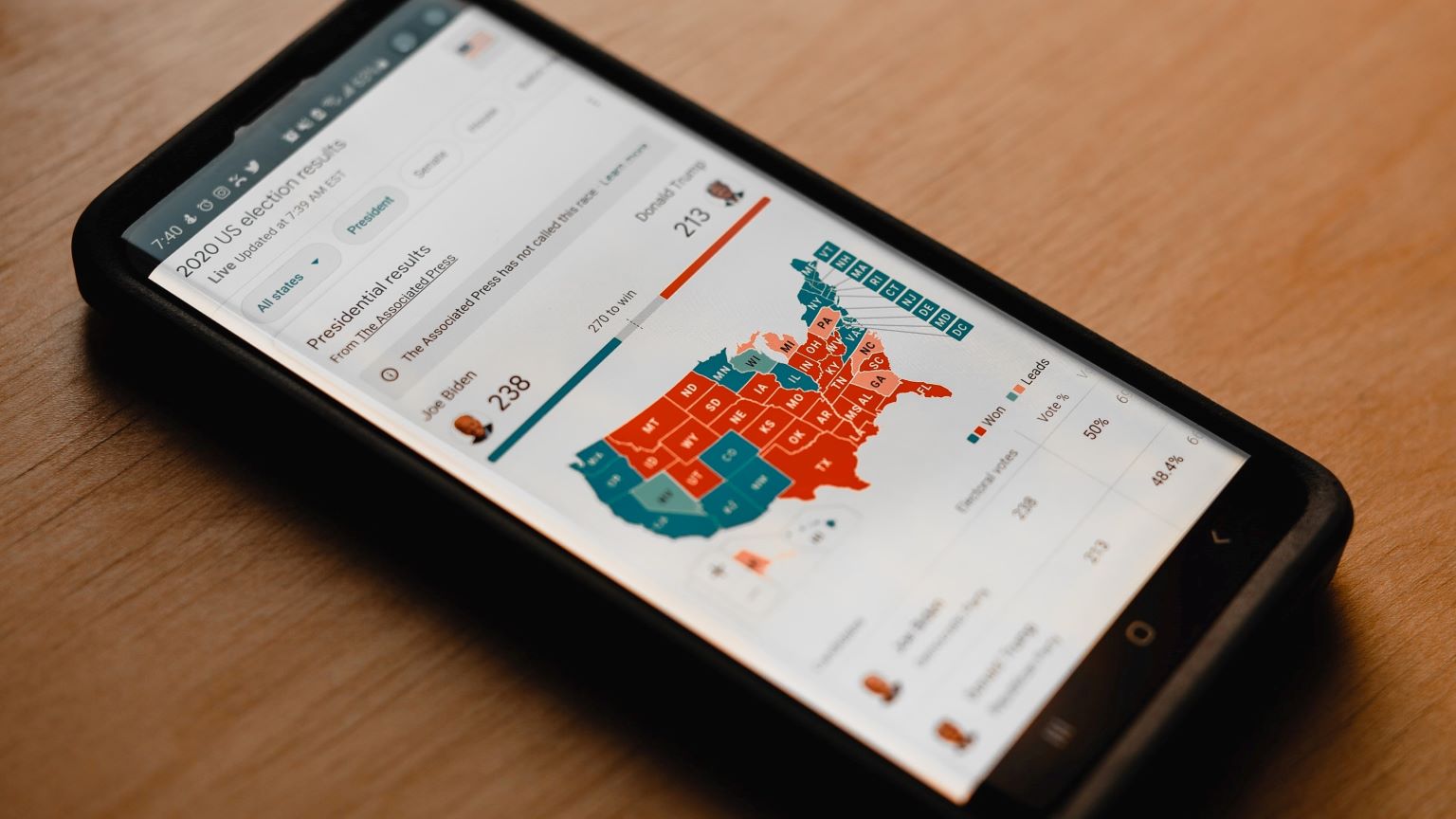

In the election of 2020, as opposed to the elections of 2000 and 2016, there was no discrepancy, viewed on a national level, between the popular vote and the vote in the Electoral College. Joseph Biden and Kamala Harris won both. In December 2020, soon after the election and the result of that election becoming clear, the losing candidate for the presidency, the incumbent President Donald Trump, demanded that his Vice President, Mike Pence, deliver him a victory through the exercise of his responsibility in the Electoral College. The Vice President is designated by the Constitution to chair the joint session of the House and Senate that is to receive and tabulate the votes of the Electoral College.

At the joint session of Congress, representatives of the various states were to present Vice President Pence slates of electors that were certified by each state governor to be in accord with the popular vote in that state. Trump’s supporters had prepared alternative slates of electors who pledged to support Trump even though he had not won the popular vote in these states and the alternative slates were not certified by the governors of those states. Such alternative slates were prepared for Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, New Mexico, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin.

Under this scheme, the alternative slates were to be presented to Pence on the assumption that they would be sufficient basis for Pence to put off certifying the victory of Biden and Harris. Still, it is not at all clear how Pence was to use his powers to turn a defeat of Biden and Harris into a victory for Trump and Pence.

Conceivably, the delay in certifying the election results might have enabled Trump to make a last-ditch effort to contest the outcome in the targeted states. Or Trump may have even been banking on the joint session of Congress to accept the alternative slates of electors even though they had not been certified by the governors, thereby selecting him and Pence as the victors of the 2020 election.

The Electoral Count Act of 1887 empowers this joint session of Congress to determine which votes should be counted whenever it concludes that the Electoral College slates representing the winning candidates were not “legally certified” or “regularly given.”

Pence balked. Well aware of the fact that Trump’s challenge to the popular votes in the states in question was rejected by every court to which it was presented, Pence refused to accede to Trump’s demand. Even the Supreme Court denied, for lack of standing, an application by the state of Texas for leave to file a complaint challenging the results in Georgia, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin.

Accordingly, Pence viewed his role in purely ministerial terms — not to second-guess the popular vote in the various states or to contest their certification, but simply to receive and tabulate the votes of the electors that were officially certified in each state and then, in the joint session, presented to him.

Rebuffed by Pence, Trump scheduled a rally to be held at the Ellipse, just outside the White House grounds and adjacent to the National Mall. He scheduled it for January 6, 2021, the day Congress was scheduled to certify the votes of the Electoral College and thus approve the election of Biden and Harris. Egged on by Trump at this rally and by some of his followers, most notably Rudy Giuliani, who called for “trial by combat,” hundreds of those who had attended the rally streamed toward the Capitol and soon turned into an angry mob.

By force of numbers, this mob breached the security of the Capitol. Some members of the mob ransacked offices. Others entered the chamber in which both the House and Senate were meeting and eventually resumed to meet once order was restored. Some even called for Pence to be lynched.

In condemning this action, the nation not only condemned the violence and the interference with the function of government that it wrought, it also condemned the threat that the mob had posed to democracy itself. The mob sought to prevent Congress, required on that very day to receive and acknowledge the votes of the Electoral College, from giving effect to the outcome of the election of November 2020 and in that way from honoring the democratic aspirations of the Constitution.