The utopian 1920s scheme for five global superstates

Image: public domain

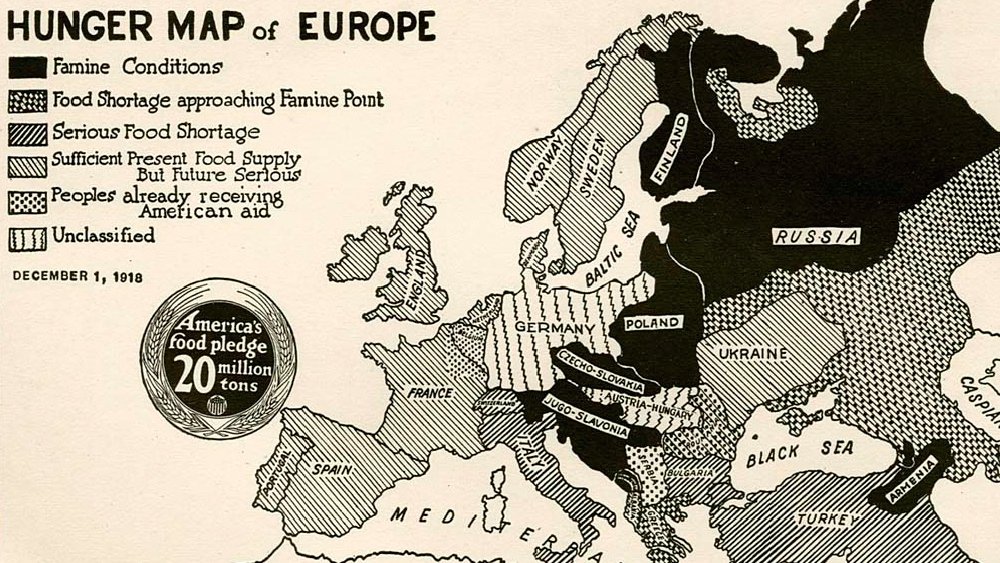

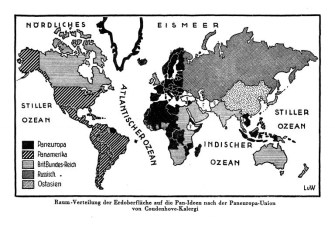

- Unity is strength: This 1920s map divides the world among just five superstates.

- The map was produced by count Richard von Coudenhove-Kalergi, who devoted his life to European unity.

- This utopian map may have inspired George Orwell’s dystopian world in 1984.

Richard von Coudenhove-Kalergi in 1926.

Image: public domain

Geopolitical dreams

If the geopolitical dreams of a 20th-century Austro-Japanese aristocrat had come true, this is what the map of the world would have looked like: dominated by no more than five super-states.

Now mostly obscure, count Richard von Coudenhove-Kalergi (1894-1972) is remembered mainly as the hero and villain (respectively) of the two fringes of the never-ending debate about European integration.

And that’s a shame, because Coudenhove-Kalergi cuts quite an intriguing figure. Not only is he the one who proposed Beethoven’s Ode to Joy as Europe’s anthem, he also served as inspiration for Victor Laszlo, the fictional resistance hero in Casablanca.

On his father’s side, Richard was the scion of an Austrian noble family with roots in Flanders and Greece and branches all over the rest of Europe. His mother, Mitsuko Aoyama, came from a wealthy Japanese family of merchants and landowners.

Original flag of the Pan-European Union. The current flag includes the twelve stars of the European Union. Co-founded by Coudenhove-Kalergi in 1922, the PEU is still in existence: its current president is former French MP and MEP Alain Terrenoire. Its HQ is in Munich.

Image: Ssolbergj, CC BY-SA 3.0

Pan-European Union

In 1922, Coudenhove-Kalergi co-founded the Pan-European Union, together with Austrian Archduke Otto von Habsburg. A year later, he published the manifesto Pan-Europa, and in 1924 he founded an eponymous journal, which ran until 1938. In 1926, the first Congress of the Pan-European Union elected Coudenhove-Kalergi as its president, which he would remain until his death.

The motivation for the count’s Pan-Europeanism was the threat of “world hegemony by Russia”. The only way to prevent that was to supersede Europe’s various nationalisms. The Pan-European superstate as envisioned by Coudenhove-Kalergi was a curious mix of social democracy and Christian conservatism – a “social aristocracy of the spirit”. In response, Leon Trotsky, then Soviet commissar, in 1923 called for a “Soviet United States of Europe”.

As in 1984 (and post Brexit), the UK in Coudenhove-Kalergi’s system is not a part of the continental European superstate.

Image: public domain

Five superstates

The original framework for Coudenhove-Kalergi’s Pan-Europeanism was a global polity of no more than five superstates, as shown on this map taken from one of his early works:

- Pan-Europe: uniting all European countries, minus the Russian and British empires. Pan-Europe also includes the French, Italian, Portuguese, Belgian, and Dutch colonial possessions, with a foothold in the Americas, half of Africa, and substantial parts of South East Asia.

- Pan-America: all of the Americas, with one major exception: Canada – controlled by the Brits. Minor exceptions include all the other bits controlled by the British and European empires. Pan-America also includes the Philippines, U.S.-administered at the time of publication.

- The British Commonwealth: basically, the British Empire at its height. Great Britain and Ireland, Canada and British Guyana, Africa from Cape to Cairo (and Nigeria, plus other territories in West Africa), the Arabian peninsula and the Indian subcontinent, Malaysia, Papua New Guinea, Australia and New Zealand.

- The Russian Empire: almost at its greatest extent. Ukraine is under the sway of Moscow, as are the Caucasian and Central Asian areas that are currently independent. But the Baltics are part of Pan-Europe.

- The smallest, but probably most populous of the five empires is East-Asia: uniting Japan, Korea and China, and also including Nepal.

The big idea behind the map is clear: There is strength in numbers, and efficiency in scale. The world is gravitating toward large zones of cooperation, and these are five geopolitical concepts that seemed like viable options to Coudenhove-Kalergi. Do note, however, that there are some countries that do not fit into the count’s world vision: Question marks cover Turkey, Iran, Afghanistan, and Ethiopia.

A map of the world in 1984. George Orwell may have been inspired by Coudenhove-Kalergi’s rather more utopian map.

Image: public domain

Nineteen Eighty-Four

The map is also a bit scary: A globe dominated by an ‘oligopoly’ of just five states suggests governments that are far removed from their citizens.

It’s a small leap from this world map to the one that informs 1984. In fact, George Orwell may have been inspired for his dystopian geography by the count’s utopian vision: One of the three superstates on Orwell’s imaginary map is in fact called ‘Eastasia’. Another one, ‘Eurasia’, could be identified with another iteration of Coudenhove-Kalergi’s Pan-Europe, without the colonial empires but including Russia.

In his later work, Coudenhove-Kalergi seems to have abandoned the global dimension of his agglomerative vision, concentrating more on unity within Europe.

His Pan-Europeanism may have been directed against the threat of the extreme left, that didn’t make it popular with the extreme right. Hitler denounced the count (and his ideas) as those of a “rootless, cosmopolitan and elitist half-breed.” The Nazis considered Pan-Europeanism a Masonic plot.

Fleeing into American exile after Austria’s Anschluss (1938), Coudenhove-Kalergi spent the war continuing to make the case for European unity. At one point, however, he also proposed to form and head an Austrian government in exile – a suggestion that was ignored by Roosevelt and Churchill.

Cover of a 1934 book by Coudenhove-Kalergi, showing another vision on Pan-Europe: without Europe’s colonies, including the territory of the entire Soviet Union.

Image: public domain.

Eurasian Union

After the war, it was others who led Europe towards greater integration, although Churchill lauded the count’s Pan-European Union for its work in a speech in 1946 in Zürich. Coudenhove-Kalergi was instrumental in founding the European Parliamentary Union in 1947 and in 1950 was the very first recipient of the annual Charlemagne Prize, awarded by the city of Aachen for work in the service of European unification.

Coudenhove-Kalergi’s grave, near Gstaad, carries the epitaph: Pionnier des États-Unis d’Europe. For all its simplicity, that sounds a bit grandiose – he was not directly involved in founding the EU or any of its precursors – not to say premature: today’s European Union is not (yet) the dreaded monolithic superstate evoked by the epithet ‘United States of Europe’.

Nonetheless, proponents of (further) European integration happily praise the count’s life-long devotion to the cause. Streets and squares throughout Europe – although admittedly never the longest or largest ones – carry his name.

On the other hand, opponents of European integration from the nationalist and identitarian camp denounce the so-called Kalergi Plan, a plot to use immigration to dilute Europe’s ‘whiteness’, supposedly penned by the “cosmopolitan” count. It’s a hoax on a par with the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, unfortunately also by token of its continued currency among those fringe groups.

Strange Maps #1002

Got a strange map? Let me know at [email protected].