Air pollution linked to violent crime in Chicago

Photo by Chait Goli from Pexels

- A new report suggests air pollution from highways increased violent crime in Chicago by two percent.

- The effect was consistent across different parts of the city and independent of other factors.

- The research suggests that a tax simultaneously could lower air pollution and crime.

Air pollution doesn’t only harm the lungs. An increasing number of studies suggest that it is also associated with lowerproductivity, reduced short-runcognition, and an increase in psychologicaldistress and evensuicide.

Now, a newstudy soon to be published in the American Economic Journal adds another potential side effect to polluted air: increased rates of violent crime.

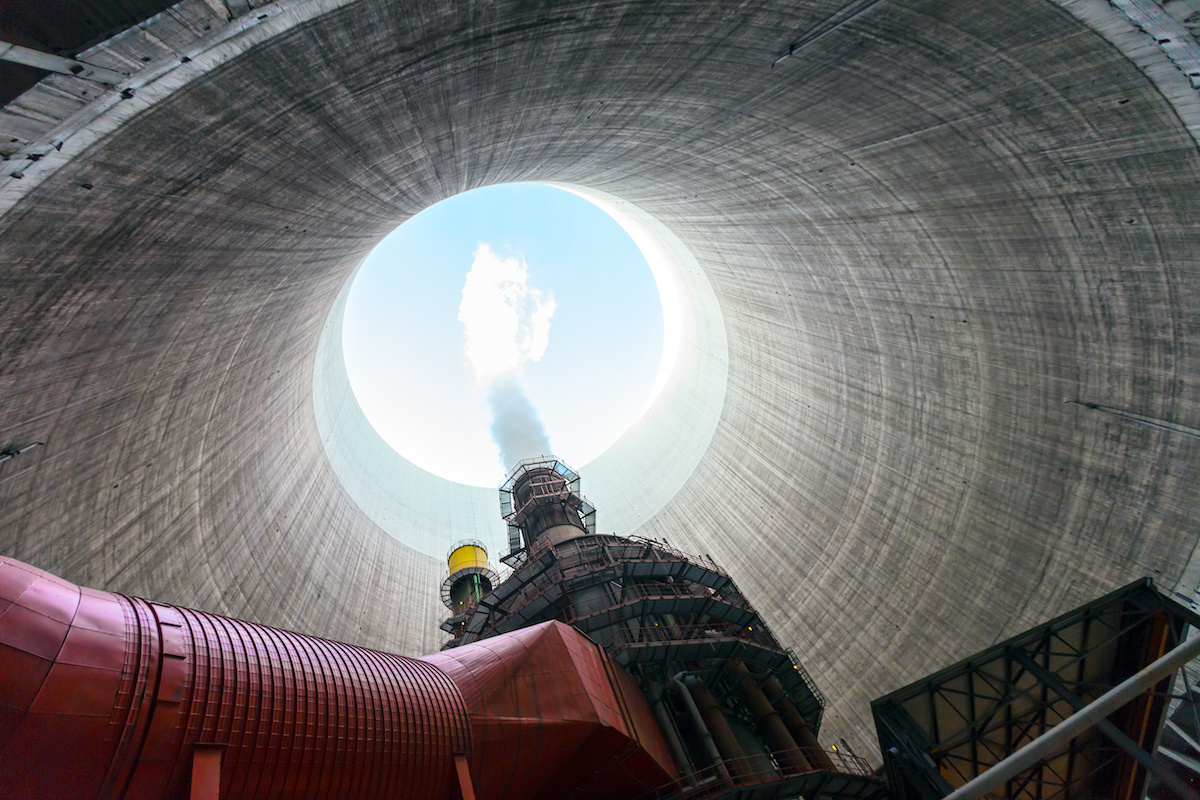

My kind of town (Chicago is)

While Chicago isn’t the most violent city in thecountry, it does have a treasure trove of data on reported crime, neighborhood pollution levels, weather, and other micro-geographical information that makes it an excellent choice for a study like this. By combining the information collected between 2001 and 2012, the authors were able to compare changes in the crime rate upwind and downwind of several major highways — namely I-90, I-94, I-290, I-55, and I-57 — on a day-by-day basis while controlling for other factors, such as temperature, that are also known to influence crime.

The study omitted areas near multiple interstates, including downtown, and the extremities of the city such as O’Hare International Airport to avoid data that was too noisy to use. Data from days when the wind was not within sixty degrees of the line orthogonal to the interstate were also excluded. Importantly, the number of major roadways considered means that the data includes areas containing all socioeconomic levels.

The authors provide the example of taking measurements for neighborhoods near I-290, an east-west roadway connecting downtown with the suburb of Oak Park:

“To causally estimate the effect of pollution on crime, we compare crimes along the north side of I-290 to the south side of I-290 on days when the wind is blowing orthogonally to the interstate. On a day when the wind is blowing from the south, the pollution impacts the north side of I-290 and vice-versa. In essence, the side of the interstate from which the wind is blowing acts as a control for unobservable daily variation in side-invariant criminal activity, driven by, for example, weather.”

In total, the effect of the wind-driven pollution amounted to roughly a two percent increase in violent crimes (homicide, assault, etc.) on the downwind side of the interstates.

There was no consistent effect on property crimes like theft or burglary. Areas further from the roadways, and thus with less pollution, saw reduced effects. The effect was also most notable when the weather was nice enough to be outside, possibly prompting people to go out, which in turn exposed them to more air pollution.

Possible long-term effects were not investigated by the authors, in part because the crime rate and pollution levels in Chicago went down over the time period considered in the study.

Why would air pollution cause crime?

The authors “do not take a stand on the exact underlying mechanism” at work. However, they do point out that their findings align with others suggesting a connection between air pollution and aggression.

Additionally, the causes of crime are often complex and multifaceted. While this study does show that pollution can increase crime rates downwind of pollution sources independently of other factors, the cause of the basal crime rate is another question entirely.

What do these findings mean for how we handle pollution?

The authors suggest that the costs of air pollution are higher than we currently calculate. For policy, this means that the optimal Pigouvian tax — that is, the tax that properly prices in negative externalities — should be higher than they currently are for products that cause air pollution, like gasoline.

Furthermore, the authors estimate that lowering crime by two percent would have saved the city $22 million dollars in social costs during each year considered in the study. If applied to the country as a whole, the reduced crime might save $2.2 billion dollars.

A tax that lowers both pollution and crime might be worth it.