How typing transformed Nietzsche’s consciousness

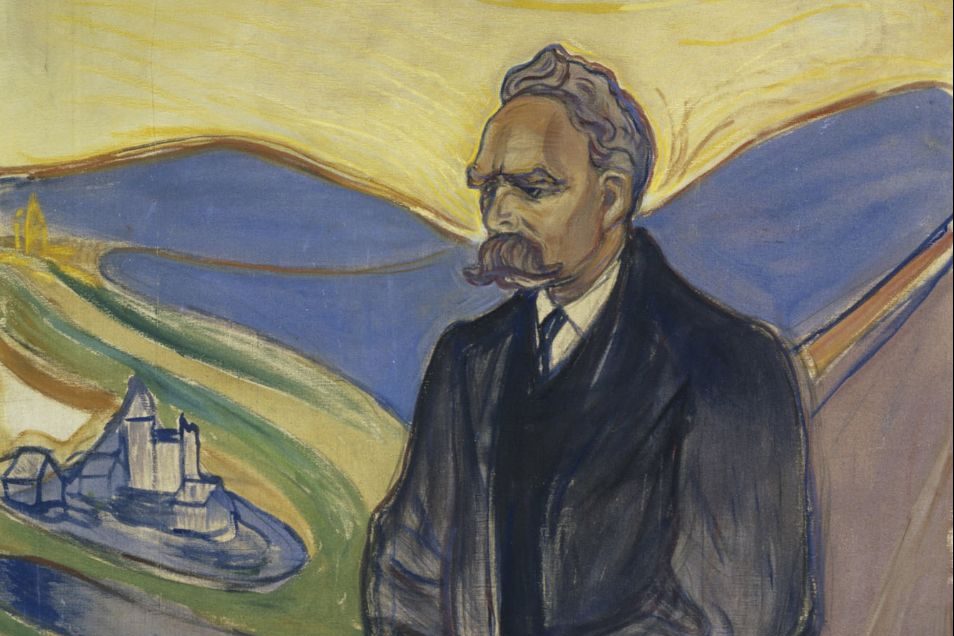

Friedrich Nietzsche has been described as — and accused of — many things, some of them strikingly contradictory. Nazi ideologues selectively appropriated elements of his philosophy, such as extreme individualism and his allegory of the Übermensch, to suit their agenda. And during the notorious Dreyfus Affair in France, anti-Semites vilified supporters of the Jewish officer Alfred Dreyfus as “Nietzscheans.”

He was seen by others as a skilled eviscerator of received ideas on science and its allegedly corrupting effect on knowledge, and yet more saw him as a dangerous nihilist. Nietzsche was also thought to have serious misgivings about the sustainability of Christianity in the context of Enlightenment and industrialization, culminating in his provocative declaration, “God is dead,” in his 1882 book, “The Gay Science.” Nevertheless, his reputation survived and recovered from its incorporation into Nazidom, and today his influence, or at least readership, is widespread. Nietzsche has been read and commented on by such diverse characters as Huey P. Newton of the Black Panther Movement and former U.S. President Richard Nixon, both of whom found something (and doubtless something different) in his “Beyond Good and Evil.” Nietzsche’s legacy persists, evident in global societies, conferences, videos, and books.

Amid all this hubbub of opinion and research into the man and his ideas, however, hardly anyone has commented on, or sought to explain, another aspect of Nietzsche: his productivity, and how it changed during his career because of his adoption of a new writing technology. Consider this: Nietzsche wrote four books between 1870 and 1881, or almost one every three years, which is pretty good. After 1881, however, he managed to deliver 10 manuscripts to his publisher in the seven years to 1888, whereupon he became too ill to write any longer. That was a book and a half per year, which is really good. By 1881 Nietzsche had become almost blind, an infirmity that would surely have hampered his longhand writing. How did he manage to improve his work rate? What he did was something seemingly out of character, given his views on modernity and science: He bought a typewriter. To be precise, he purchased a top-of-the-line portable Malling-Hansen writing ball, which was sent specially to him from its inventor in Copenhagen.

On the face of it, there’s nothing so remarkable about this. A practiced typist can produce a page of text very much faster than can someone trying to write the same words in longhand. And as he became more used to the modern technology, this was doubtless a factor in Nietzsche’s efficiency with words. But it’s more than efficiency. It’s more than the fact that the efficiency of the Gutenberg press was in its capacity to print page after page of the same words much faster than was humanly possible before its invention. And it’s more than the fact that the efficiency of the Jacquard loom was coded into a program that could replace aspects of the ancient human role in weaving.

These examples represented significant breaks with how we produce through our interaction with technology. Nietzsche became more efficient. But Nietzsche was not an industry. He was a thinker. Typing transformed Nietzsche’s consciousness — it affected how he thought about and expressed the world as he understood it. The literary scholar Walter Ong has said that writing as a technology was not simply an exterior aid but an “interior transformation of consciousness”: It took hold of human consciousness 3,000 years ago and changed it, with the written word representing thought itself. Written words were embedded into the consciousness of the literate to imprint a kind of thought grammar that reflected the world as they read and wrote about it.

Nietzsche’s near industrial-scale productivity and efficiency came with a cost — or was it a benefit? — to how he thought and wrote before. Blindness forced him to stop writing longhand with pen and ink and instead use his fingertips to identify the fixed arrangement of letters on the Malling-Hansen writing ball. Inevitably, the grammar of the mechanical writing ball overrode the schooled grammar of longhand writing and the thought that it produced. The sudden mechanical punctuated strike of the typewriter contrasted starkly with the ruminative flow of the pen; the typewriter encouraged a binary decision, to depress the key or not; whereas the pen with its store of liquid ink, held by surface tension in the nib, or in a small reservoir in the fountain pen, was a more latent and nonmachinic technology. The first is an incipiently digital form of thought expression, the second more innately analog; one the beginning of the forming of what literacy theorist Maryanne Wolf would call the “digital brain,” the other a brain formed in print culture and in the Romantic ambivalence toward science, Enlightenment, and machines.

Once he had mastered the skill of the touch-typist, Nietzsche’s thoughts must have really flown onto the pages of typescript, enabling him to produce a new manuscript regularly in under a year. However, like the saying “for the person with a hammer, everything begins to look like a nail,” Nietzsche’s machine-made words, and therefore his thought, adopted a new form of technological determinism. The typewriter, with its capacities and its limits, its opportunities, and its curtailments, restructured his consciousness and therefore reorganized his philosophical and creative expression. What was able to be thought and written in, say, “The Birth of Tragedy” of 1872, when Nietzsche’s eyesight still held and longhand was his written form, was something no longer possible once his eyes failed him and he got behind the Malling-Hansen. A very different writing technology helped to determine another way of thinking and the expression of these thoughts through writing. The agency and control inherent in wielding a pen, even though this too shaped and formed thoughts for millennia, was transformed when tapped out from a rigidly positioned set of mechanical keys. How was that difference expressed?

The German philosopher of technology Friedrich Kittler has claimed that the analog typewriter in general was useful for certain forms of thought: the brief, the succinct, the forms that thrive on concision and quickness. Kittler looks at the case of Nietzsche and argues that “Nietzsche’s reasons for purchasing a typewriter were very different from those of his colleagues who wrote for entertainment purposes, such as Twain, Lindau, Amytor, Hart, Nansen, and so on. They all counted on increased speed and textual mass production; the half-blind, by contrast, turned from philosophy to literature, from rereading to a pure, blind, and intransitive act of writing.”

What would in the mid-20th century come to be called the “culture industry” would thrive on this modern technology and the productivity it enabled in commercialized culture, such as literature, movies, and television. But it posed an existential problem for philosophy and philosophical thought. The transformation in Nietzsche’s writing due to his écriture automatique was so marked, indeed, that it was even noticed at the time. In 1882, the Berliner Tageblatt commented on the onset of Nietzsche’s “complete blindness” and wrote that “with the help of a typewriter [he] has resumed his writing activities.” However, the article gave notice: “It is widely known that his new work [‘The Gay Science’] stands in marked contrast to his first, significant writings.” For Kittler, the contrast was indeed marked. He notes that the character of Nietzsche’s writing and therefore, his thought processes had, via the mediation of the typewriter, been significantly recast. As Kittler saw it, a celebrated Nietzschean style comprising sustained reflection, long sentences, and complex reasoning had changed “from arguments to aphorisms, from thoughts to puns, from rhetoric to telegram style.” Nietzsche was an early adopter of the technology. He took it to the heady realms of Continental philosophy and — if we consider his immense influence — began to change it through a creative mind that was reshaped by the keys that had replaced the pen.

Nietzsche may not have appreciated this evaluation, but he did seem to realize in his now-sightless world that something important had occurred in his thinking processes. As Kittler again tells us, in one of the few letters Nietzsche wrote on a typewriter, and anticipating Marshall McLuhan, Nietzsche stated, “Our writing tools are also working on our thoughts.” He undoubtedly was aware of his increased productivity, but as to the quality and substance of the content, as its creator, he perhaps was not best placed to judge. Kittler, for his part, was clear on what was happening with this technology at the general level of philosophic thought.

Philosophy, or the thinkable and expressible elements of it via mediation, changed fundamentally with the gradually more widespread adoption of “automatic writing” and with it the culture it would produce for most of the 20th century. Kittler noted a turning point for Nietzsche in his “Genealogy of Morals” from 1887. This book, an immensely influential volume on moral concepts, Kittler reads as symptomatic of an evolutionary change in human thought not only in Nietzsche but in Western philosophy itself. Genealogy, in other words, prefaced the technological evolution of machine memory in computing, which was being played out in nascent form in the action of Nietzsche tapping out his philosophy through a fixed array of letter keys. Kittler writes: “In the second essay of ‘Genealogy of Morals,’ knowledge, speech, and virtuous action are no longer inborn attributes of Man. Like the animal that will soon go by a different name, Man derived from forgetfulness and random noise, the background of all media. Which suggests that … during the founding age of mechanized storage technologies, human evolution, too, aims toward the creation of a machine memory.”

The typewriter that changed Nietzsche had a long time yet to cast its spell on humanity. From that time until more recently, what Maryanne Wolf called the “writing brain,” the “mechanical” brain that had been formed out of the effects of the Gutenberg press, would serve to “industrialize” not only the mind but the economies, cultures, and societies that humans would erect. And this mechanical cast of mind would be the basis for the modern analog world in all its forms, especially its 20th-century articulations with its successes and failures.

Robert Hassan is Professor of Media and Communication at the University of Melbourne. He is the author of several books, including “The Age of Distraction” (Routledge) and “Analog,” from which this article is adapted.

This article appeared on JSTOR Daily, where news meets its scholarly match.