How Rome’s terrible 7th king led to the Republic

- The myth of Romulus and Remus bears similarity to other famous myths and may have roots in ancient Italian folklore as well.

- Though historians refer to the “seven kings” who ruled early Rome, it is likely that there were dozens whose names went unrecorded.

- The last king of Rome, Tarquin the Proud, left such a bad taste in the mouths of his constituents that they created an entirely new political system: a republic.

The founding of Rome, like so many important cities from classical antiquity, is shrouded in mystery. That is not because the early Romans failed to record their history in written form. They did, but virtually all their records were destroyed when Brennus, the king of the Senone Gauls, sacked the city in 390 BC.

Today, stories of Rome’s founding have survived in two forms: the accounts of later historians such as Livy and Tacitus, based on oral traditions collected from Italy and Greece, and works of literature. Chief among these literary works is Virgil’s Aeneid, an epic poem written between 29 and 19 BC, which professes that the Roman people descended from the Trojan general Aeneas.

Although Virgil wasn’t the first to connect the mythical hero to Rome, the Aeneid is certainly more fiction than fact. Scholars have long noted that the propagandistic poem, written during the reign of Augustus, not only presents the creation of the Roman Empire as inevitable but also legitimizes the rule of the first emperor and his bloodline.

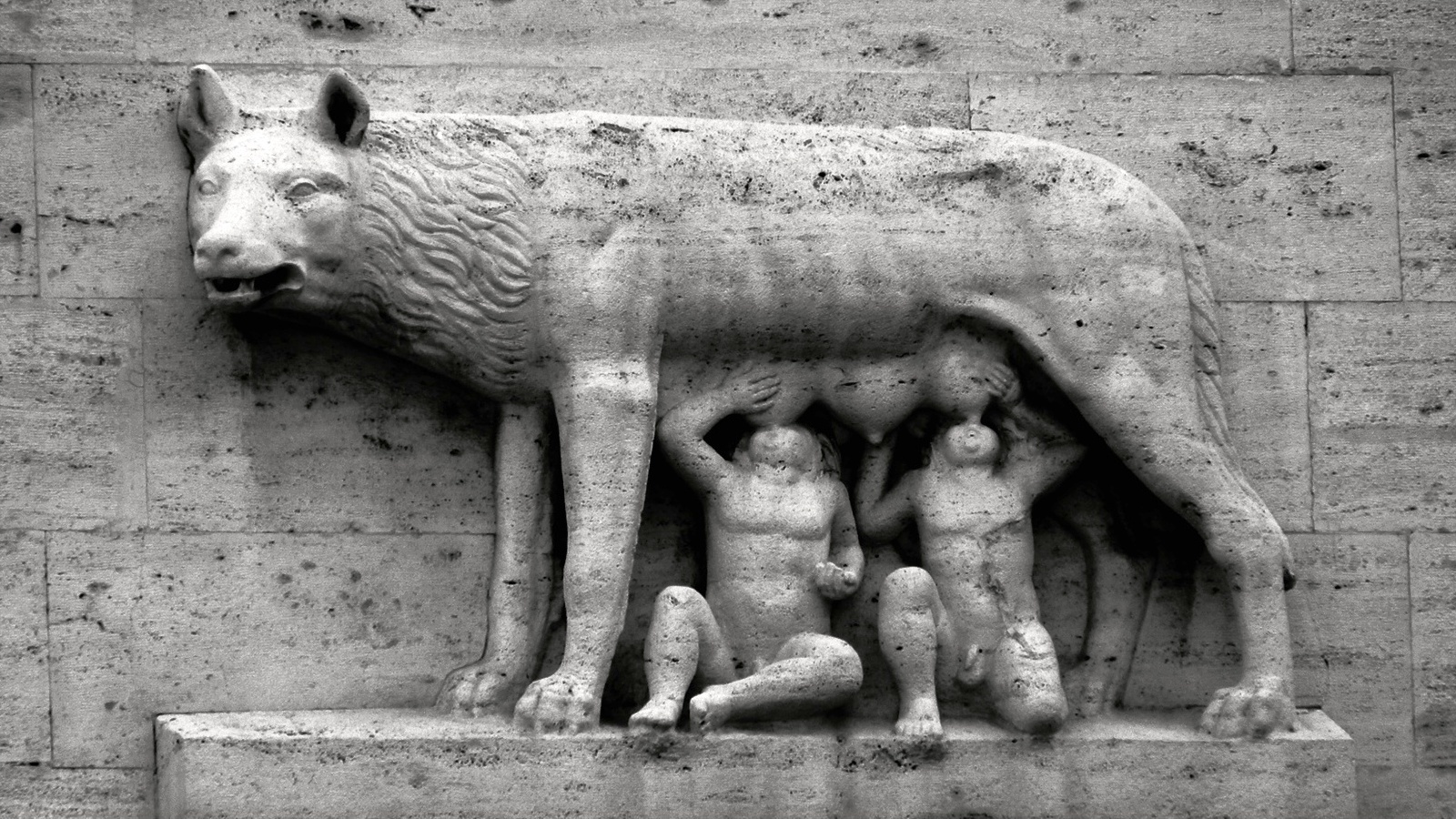

Romulus, Remus, and the she-wolf

Rome itself is believed to have been founded by Romulus, who — alongside his twin brother Remus — was born to the daughter of a deposed Latin chieftain circa 770 BC. Political rivals left them on the flooded banks of the river Tiber. Here the twins would have died were it not for a she-wolf who nursed them until they were discovered and taken in by local farmers.

Saved from death, Romulus and Remus grew up to become fierce warriors. After restoring their grandfather as chieftain, the twins set out to establish a settlement of their own but disagreed on who should be in charge. Different iterations of their legend reach the same conclusion: Romulus kills Remus, crowns himself king, and names his city Rome, after himself.

This turn of events, like the Aeneid, was probably fabricated as well. For one, scholars have pointed out numerous similarities with other European and Asian myths. These myths are filled to the brim with legendary twins, from Castor and Pollux to Yama and Yami. Meanwhile, the image of a baby cast in a river serves as the opening to the Book of Exodus, too.

Wolves also show up frequently in folklore from the Italian peninsula. They were worshipped by several tribes, such as the Hirpini and the Sabines. A 2,400-year-old relief from Bologna — once populated by the Etruscans — depicts the animal nursing a single child, suggesting Romulus and Remus were not the only mythical Latin children with a lupine upbringing.

The seven kings of Rome

While historians refer to the “seven kings,” the term is probably a misnomer. As the author Mike Duncan puts it on his podcast The History of Rome, it is highly unlikely that seven consecutive rulers stayed in power for an average of 30 years each. More likely, the legacies of several dozen kings were amalgamated into a handful of noteworthy individuals.

One such individual was Numa Pompilius, who succeeded the late Romulus as the second king of Rome. A religious individual of Sabian origin, Numa assumed the office not because he wanted to, but because he was the only person in the Italian peninsula who enjoyed the unanimous support of Romulus’ followers.

Numa couldn’t have been more different from his predecessor. Where Romulus was a vainglorious warrior who took fate into his own hands, Numa was a humble servant of the gods who abhorred bloodshed. During his staggering (but questionable) 43-year reign, the second king laid the foundation for Rome’s civic codes and religious rites.

Subsequent generations of Romans remembered Numa for establishing fetial law, a code that prescribed how Rome ought to conduct itself in armed conflict. Under Romulus, the Roman army did as it pleased. Under Numa, soldiers had to issue an official declaration of war before they were allowed to attack their enemy.

These seemingly trivial formalities, said the statesman Cicero in his Republic, “restored to humane and gentle behavior the minds of the men who had become savage and inhuman through their love of war.” And so Numa established “two things that are most important for the long life of a commonwealth, religion and mildness of character.”

The supposedly unblemished peace of Numa’s reign was quickly broken by his successor, Tullus Hostilius. Fearing that other Latin tribes no longer feared the Romans, Hostilius sought any excuse to declare war, and if he could not find one, he invented one. The third king decimated the Albans, incorporating the survivors into Rome and greatly expanding its population.

From kingdom to republic

However, perhaps no ruler made as powerful an impact on Rome as its seventh and last king, Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, later known as Tarquin the Proud. Tarquin claimed the throne after assassinating his wife, his brother Arruns, and finally Servius Tullius, the sixth king and Tarquin’s father-in-law.

Tarquin’s grievances with his predecessor were manifold. Rather than being elected by the Senate, as had been the custom since Numa, Servius was crowned king by his own predecessor’s queen. Born a slave, he had confiscated land from Rome’s patrician upper class and redistributed it to the working poor.

Despite these grievances, Tarquin ultimately proved to be a poorer king than Servius ever was. He erected monuments to himself using patrician money and plebeian labor. Worse, he murdered senators whom he suspected of treason, reducing the size of the senate and, by extension, extending his personal power.

Every transgression pushed the Roman people closer to rebellion, which finally occurred between 508 and 507 BC when Tarquin’s equally despotic son, Sextus, raped the daughter of a well-respected Roman named Lucius Tarquinius Collatinus. Collatinus, along with his friend Lucius Junius Brutus, managed to overthrow Tarquin and banish him from the city.

The abridged history of Rome holds that Collatinus, Brutus, and their followers were so traumatized by Tarquin’s tyranny that they vowed never again to elect a king. In reality, the shift from kingdom to republic may have been more gradual. As historian T.N. Gantz puts it, the purpose of the uprising was not to abolish the monarchy outright but to seize power within the system.

Still, a republic did eventually emerge, one whose legal framework was completely different from the state founded by Romulus. To prevent the rise of another Tarquin, the Romans introduced checks and balances that distributed power across different individuals. Instead of one king, the Republic would be stewarded by two consuls, both of whom served for fixed terms.

Where life in Rome previously revolved around the king, the Republic was founded on laws. These laws took precedence over everything. When the sons of Brutus, one of Rome’s first consuls, were caught trying to restore Tarquin, their own father staged the execution. It was the first major sacrifice a Roman would make in the name of his new state, but it certainly would not be the last.