“Game of Thrones” in real life: How kinship changed war in early modern Europe

Amadée Forestier/Public Domain

- A new paper finds that royal marriages were able to reduce wars in proportion to how closely they bound dynasties together.

- The most peaceful century in the history of Early Modern Europe was the most intermarried.

- The exact mechanism causing this is not fully determined, though the authors suggest a large part of it was easing diplomacy.

European monarchs tend to be related to each other. It was seen as advantageous at the time to marry off children to those of royal families in other countries. This had consequences, some bad, some good.

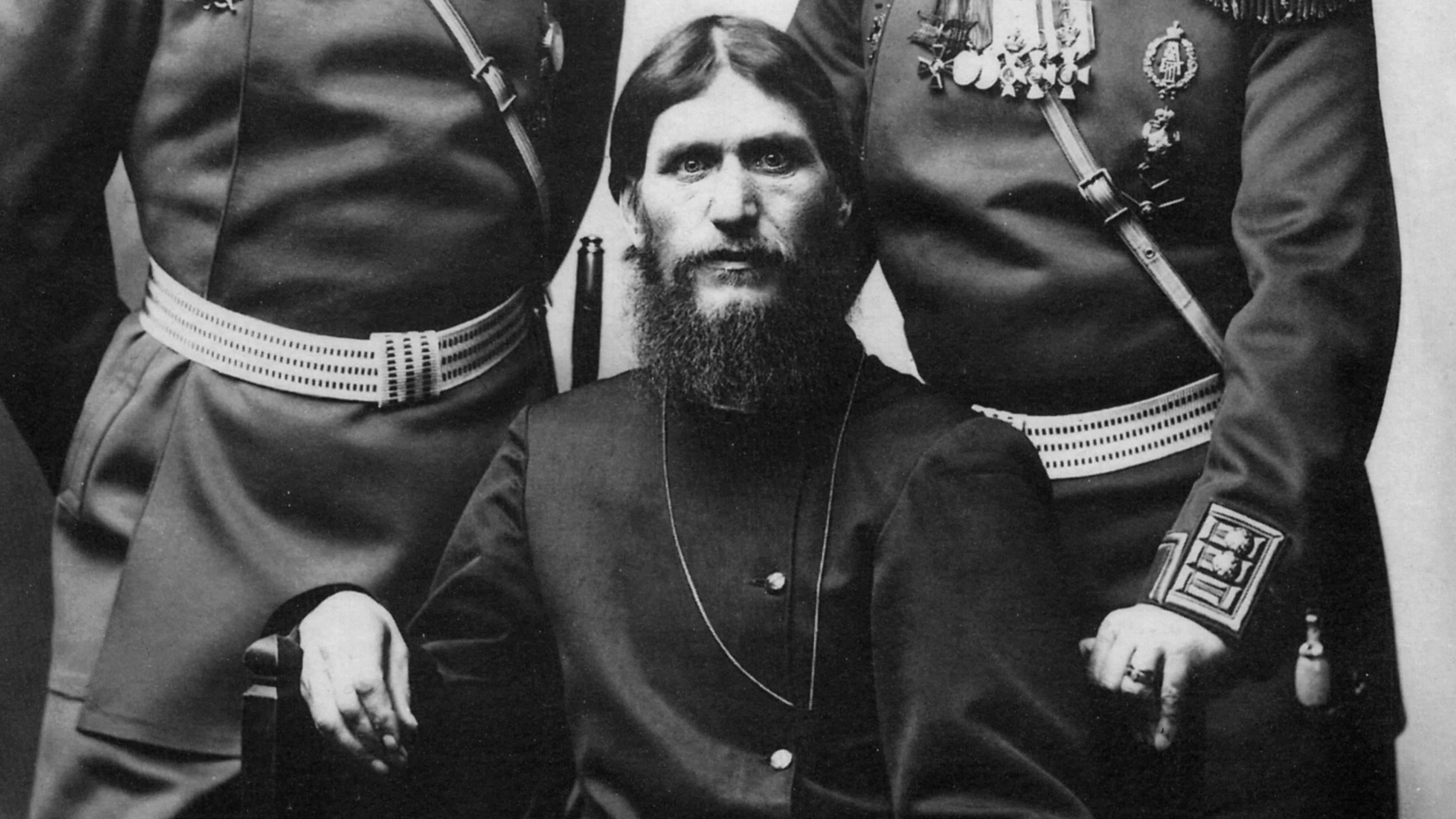

One bad consequence was the spread of the genetic disease hemophilia across the continent. A granddaughter of Queen Victoria gave her Russian son Alexei the disease, possibly changing the course of world history. A good consequence, as reported in a new paper published in the American Economic Journal, was that intermarriage between royal families seemed to decrease the number of wars. The closer the relation between the monarchs, the less likely they were to go to war.

Family matters

The authors considered data on European monarchs and the wars they fought between 1495 and 1918. By combining this information with historical records of conflict, they were able to determine the relationship between how closely related national rulers were and their likelihood of going to war.

In a development that won’t be surprising to fans of Game of Thrones, they demonstrated that countries ruled by individuals with family ties were much less likely to be at war with one another. The effect wasn’t minor either; a pair of rulers with married children were 9.5 percent more likely to go to war with one another if that marital relationship dissolved.

The most important factor for determining how likely a “dyad” (monarchy pair) would go to war was their closeness on the family tree. The closer the relation, the less likely the war. However, more distant relations increased the likelihood of war, as did the death of a mutual relative.

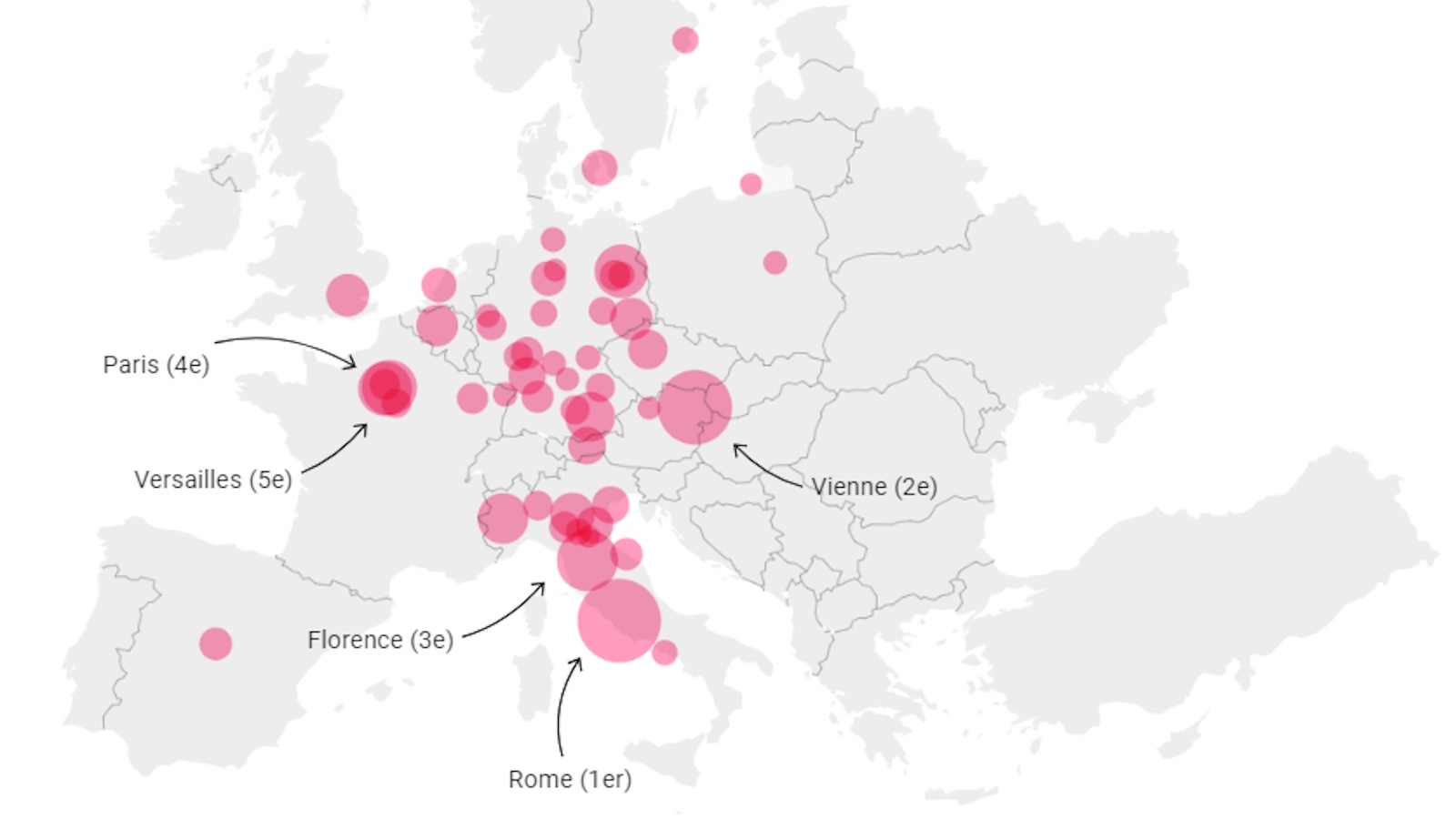

As shown in the above chart, the number of wars fought in Europe (red dots) went down as the interconnections of the monarchs increased (blue dots). These connections are at their nadir before the Thirty Years’ War and reach new heights during the 19th century, a time of relative peace. During that time, an alliance explicitly deemed a fraternity of emperors existed to keep the peace. Would such a thing have been possible if the rulers were less closely related?

There is a noticeable objection. Right before World War I broke out, the number of interconnections was still increasing. However, the authors are suggesting that the closeness of rulers is lowering the chances of war, not guaranteeing against it. Indeed, many rulers used royal marriage to try to make former foes less likely to fight them, with varying degrees of success. Thus, the benefit of the network of thrones is that there were so few wars in the years leading up to WWI.

WWI started after Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated. Why? Study co-author Dr. Seth G. Benzell explained in an email to Big Think:

“Ferdinand’s assassination wasn’t just a convenient Casus Belli. Rather, it was the Archduke’s special place in international politics — as a backup Austrian Emperor, personal friend of Kaiser Wilhelm II (himself a cousin of Tsar Nicholas and King George V) and moderate regarding the cause of Balkan nationalism — that made his removal from the international system so important. He utilized his networks to be a powerful force for peace and de-escalation at the most important nexus of the European system.”

On the whole, the authors suggest that 45 percent of the decline in the frequency of wars in 19th century Europe can be attributed to this network of thrones.

Keep it in the family

The authors suggest that royal interconnections increased the rewards of peace, making diplomatic solutions to conflict more appealing. They also propose that royal marriages could lead to increased trade between two countries, reducing the likelihood of war.

Relationships aren’t the whole story, of course. While nearly half of the decline in wars can be attributed to the network of thrones, there were other elements at play. As Dr. Benzell explained, other important factors included explicit attempts by European leaders to maintain a balance of power, an awareness of the need for states to work together against separatists, and refocusing military resources towards colonial ventures.

What meaning does this have now that monarchs don’t do much?

Today, royal weddings are mostly fodder for tabloids. European monarchs don’t really do anything. There are probably more important reasons why the UK and Greece haven’t gone to war lately than the fact that Queen Elizabeth II married a Greek noble.

Dr. Benzell suggests that the takeaway is a reminder that leaders are people too:

“The most important lesson is that the individual identities of leaders matter. So often international relations ‘realists’ take the hard-line view that it is power, strategy, and interests that are the only important factors in international politics. The world is a big game of Risk or Diplomacy, with every country acting optimally given it’s resources and objective ‘victory conditions.’ But what this research emphasizes is that leaders are people with families, and many of them care about their families more than national strategic imperatives! Diplomats ignore the personal interests and desires and friendships and dalliances of leaders at their peril.”