A surprising find inside the walls of Notre-Dame

- Archaeologists studying the rebuilding of Notre-Dame have discovered that iron staples used in the original construction date back to 1163.

- This makes Notre-Dame the first Gothic cathedral to have used iron so extensively.

- The iron staples may have been forged from recycled scrap metal or came from numerous sources throughout the long construction process.

On April 15, 2019, millions watched in horror as Paris’ storied Notre-Dame cathedral burned, seriously damaging the treasured 800-year-old holy monument. But the tragic blaze yielded a hidden blessing for archaeologists. Allowed to delve into the structure’s innards as never before during the ensuing reconstruction (which is set to finish in 2024), a team of French scientists has gleaned new insights into the cathedral’s original construction.

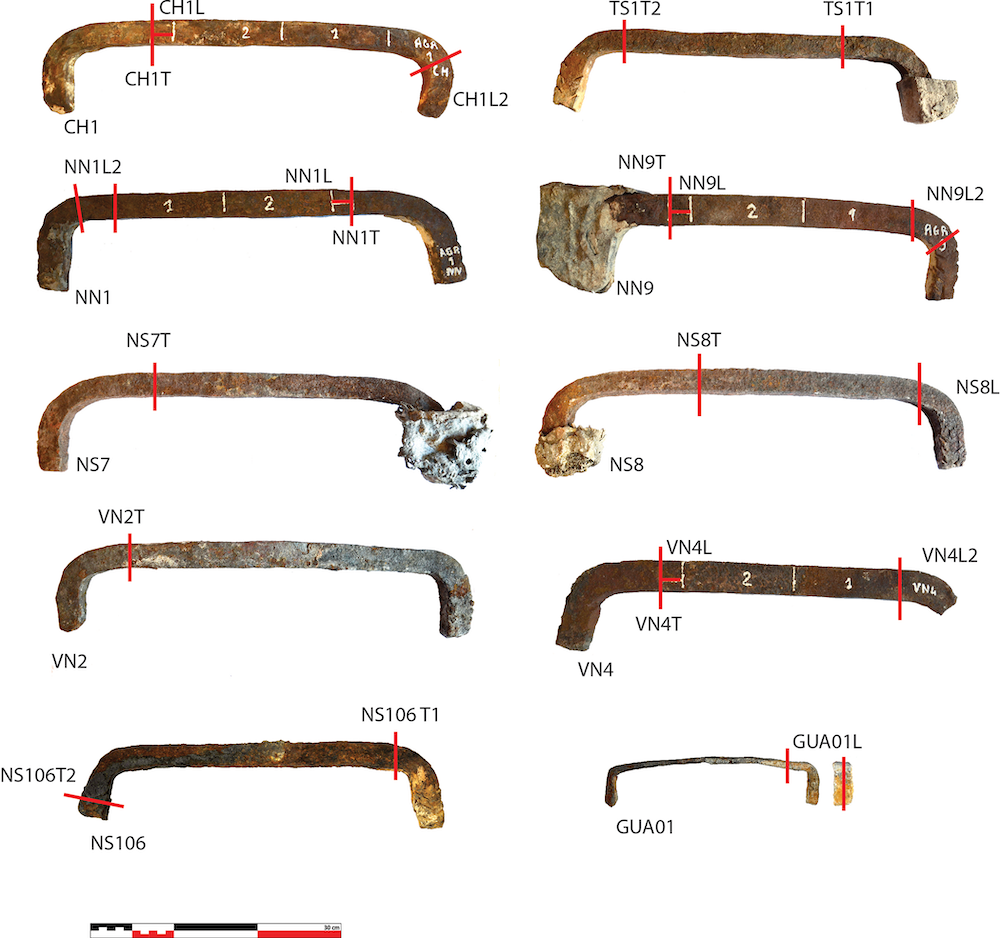

As the researchers recently detailed in a paper published in the journal PLoS ONE, they discovered large iron staples present in the building’s stonework, including the walls, columns, and tribunes.

The presence of these metal pieces isn’t altogether surprising, but what did come as a surprise is their age. Using a novel radiocarbon-based dating method, the team found that the iron staples hailed from Notre-Dame’s original construction — not from subsequent renovations in the 18th and 19th centuries.

That’s a big deal. As the researchers wrote, this makes Notre-Dame “the first known Gothic cathedral where iron was massively used as a proper construction material to bind stones throughout its entire construction.”

“Whereas other buildings used wooden tie rods stretched between the arches… the first master builder of Notre-Dame de Paris made the bold choice of a system using a more durable material that could be more easily concealed,” the researchers added.

Notre-Dame was debatably the most advanced building in the world at the time of its completion. Work on its primary structures began in 1163 and continued for another half-century — longer than most people lived in the Middle Ages! At the time, Notre-Dame was the tallest building in the world, measuring 32 meters (105 feet).

Permitted to remove a few of the staples and investigate them more closely, the researchers found that each weighs between 2 and 4 kilograms and varies in length from 20 to 50 centimeters (8 to 20 inches). These were some heavy-duty fasteners.

“The most striking feature about Notre-Dame’s staples is however the number of welding lines that can be observed in their microstructures,” the researchers commented, “indicating that several pieces of iron, sometimes from different provenances, were welded together to form each staple.”

This suggests that the iron staples may have been forged from recycled scrap metal. But while the reuse of metals for construction was common in the Middle Ages, the researchers are skeptical that this practice was used for such an important, well-financed, and ornate building as Notre-Dame.

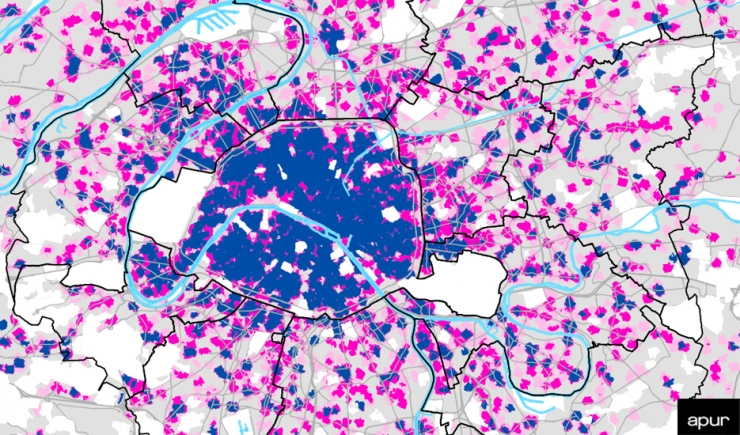

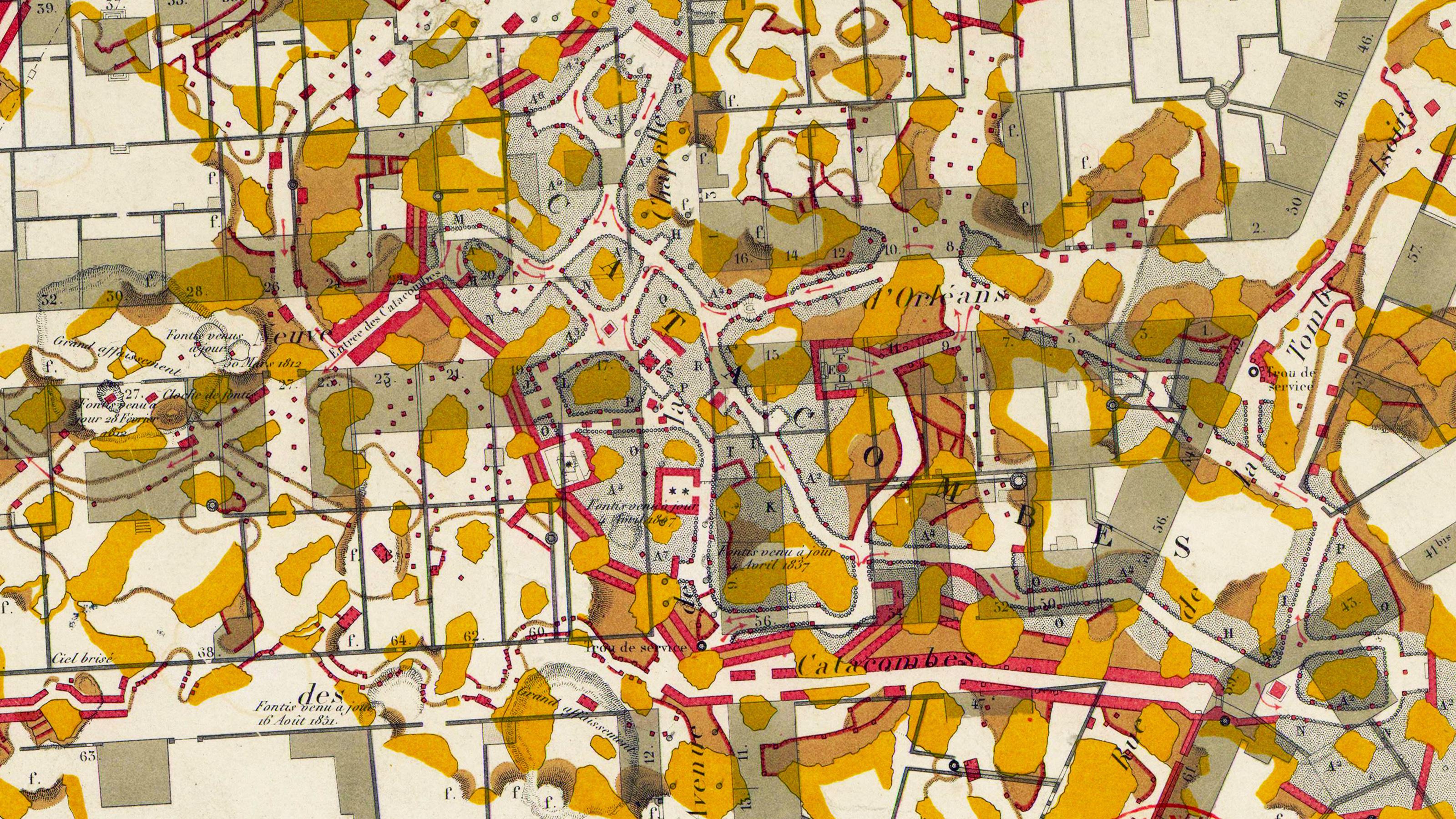

Another explanation the researchers entertained: Notre-Dame’s builders may have received iron from numerous sources by road and by river throughout the lengthy construction process, which means that there might have been a thriving iron market around Paris at the time.

“These results need to be reinforced with the opening of the Notre-Dame restoration yard and accessibility to new structures thanks to the dismantling of stone and repair of the framework,” they cautioned.

Already during the reconstruction process, archaeologists have uncovered painted sculptures, tombs, and even lead sarcophaguses. More discoveries are sure to be made public as scientists continue to probe Paris’ iconic medieval monument.