Nobel disease: Why some of the world’s greatest scientists eventually go crazy

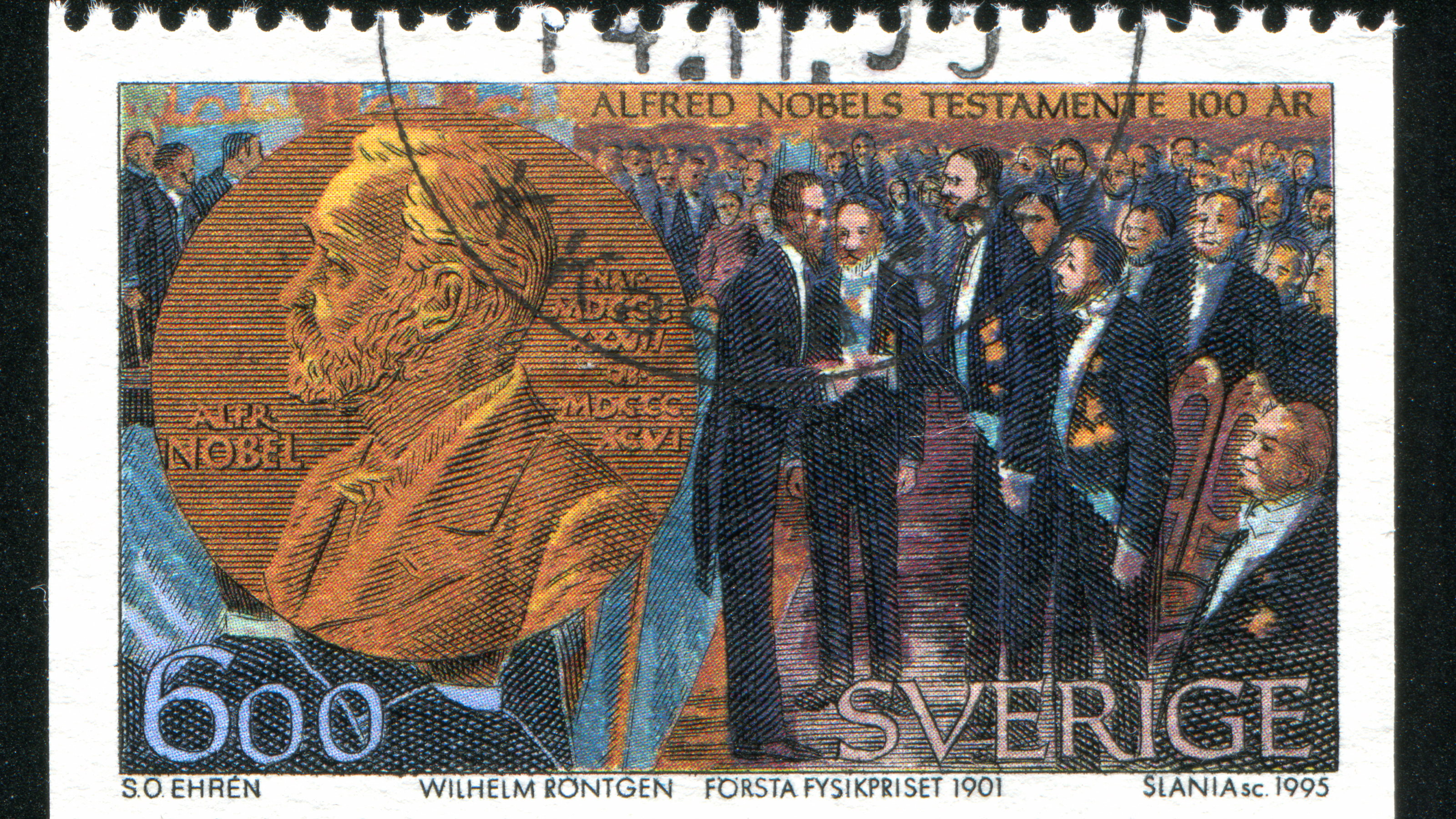

- Winning the Nobel Prize is the ultimate professional achievement for a scientist.

- The honor is so great, that a Nobel Laureate may feel as if their ideas and judgments should never be questioned again.

- This aloof status, along with the pressures of fame, can cause Nobel Laureates to spend their later years chasing impossible, pseudoscientific, or outright insane ideas.

Winning a Nobel Prize in the sciences may be the most prestigious achievement in the world. It’s the ultimate golden ticket. Professionally, a Nobel Laureate in physics, chemistry, or medicine can spend the rest of their career wherever they choose, studying whatever they want. Laureates become spokesmen for their fields, or they can lead institutes or head government agencies. They represent the pinnacle of human achievement.

But fame comes with downsides. Laureates are often asked to comment on things far outside their area of expertise. This can be fraught with danger, particularly if the topic involves something of wide public interest, like politics or religion — or aliens. Though he wasn’t a Nobel Laureate, Stephen Hawking regularly found himself in such situations — and he often said incredibly dumb things.

There are professional pitfalls as well. While most successful scientists attack tractable problems, a Nobel Laureate often finds it hard to focus on anything but the very grandest challenges. Albert Einstein made so many earth-shattering discoveries that he could have won four more Nobel Prizes; instead, he spent his later years chasing futile grand unified theories of everything. Likewise, Steven Weinberg, another giant in the field, spent decades mired in string theory, chasing in his own “final theory.” Nobel winner Richard Hamming described it this way: “Now he [another winner] could only work on great problems.”

The problem with great problems is that it often leads to a Laureate developing what is called “Nobel Disease,” a tongue-in-cheek term that describes the hubris and unwarranted self-confidence that often comes with winning a Nobel Prize.

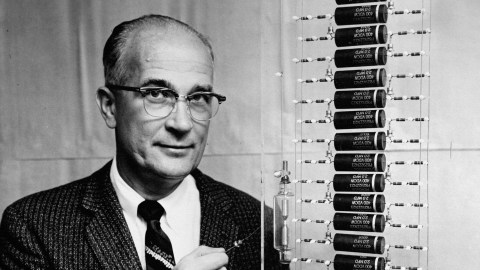

Shockley’s shocking behavior

William Shockley was one of the inventors of the modern solid-state transistor at Bell Labs. (He made sure everyone knew this by claiming credit for his collaborators’ work, horning in on their publicity photos, and trying to push them off the patent.) For this, among other discoveries, Shockley earned a share of the 1956 Nobel Prize, along with his colleague John Bardeen. Bardeen, known for his humble, easygoing nature, grew tired of Shockley’s behavior and left Bell to become a professor. In this position, he turned to the problem of superconductivity. His new work won him a second Nobel Prize in physics.

Shockley, on the other hand, developed Nobel Disease. He founded the first transistor company in what would come to be known as Silicon Valley, and his reputation and intellectual gifts attracted top young physicists to staff it. However, winning the prize unleashed the worst of Shockley’s traits. His paranoia swelled to the point that he forced his employees to undergo polygraphs. In thrall to his egotistical need to be seen as a great genius, he made them work on his brilliant but impractical ideas and publicly humiliated them when these quests failed. His arrogance finally forced what he called “the traitorous eight” of his talented protégés to quit. These men went on to become famous for their own brilliant work: founding Intel, inventing modern chip technology, and creating integrated circuits.

After this disaster, Shockley returned to academia but gradually left the field of physics to dive into questions about race and intelligence that ultimately led to his becoming a public spokesman for eugenics. He trashed his first wife for her allegedly “inferior” genetics that made his children less intelligent, donated sperm to a special Nobel winner sperm bank, and got himself banned from campuses. By the time he died, Shockley was a certified nut who taped his conversations with reporters who in turn trolled him for laughs.

From science to pseudoscience

Another physicist, Brian Josephson, won the prize for solo work performed at age 22 that formed his PhD thesis. (This is stunning, like winning the Indy 500 while you’re still studying for your driver’s license.) With another 40-plus years ahead of him, how could he live up to this success? No one could question Josephson’s brilliance or judgment to pursue new ideas. So, he picked up an interest in transcendental meditation, which apparently led him to spend half a century studying and sometimes supporting telepathy, parapsychology, psychokinesis, and other New Age woo.

Josephson is not deterred by crushing criticism from his peers. He continues to look for true psychics and paranormal phenomena. And he’s also into cold fusion.

Several other Laureates have found similar later career disgrace: James Watson, co-discoverer of the structure of DNA, became known as a racist. Linus Pauling spent his later years advocating various kinds of alternative medicine. He campaigned so well for the bogus idea of Vitamin C as a treatment for everything from old age to cancer to common colds that, to this very day, many people load up on Vitamin C when they start to feel sick. Luc Montagnier, a co-discoverer of HIV, went on to become a public proponent of various fringe medical theories.

Sympathy for Nobel Disease sufferers

It’s easy to mock and dismiss Laureates who succumb to Nobel Disease. Who feels sorry for a stubborn or arrogant person who spouts nonsense? Yet, we must keep in mind that eccentricity often accompanies brilliance. When the pressures of fame are added to the mix, this can push some of these quirky people over the edge. So, we should have some sympathy; for some, the disease is a side effect of greatness.