New DNA testing reveals who made ancient stone tools

- When discovering new artifacts, archeologists sometimes make assumptions about which distinct human lineage they belonged to.

- Stone tools found in a cave in Ranis, Germany, were originally thought to be made by Neanderthals but new fossil evidence suggests they were produced by early humans.

- The find represents evidence for some of the the earliest Homo sapiens in Europe.

By analyzing the DNA from newly discovered fossils near ancient artifacts, archaeologists have solved the mystery of who made a class of stone tools — and revealed that humans expanded across Europe faster than previously thought.

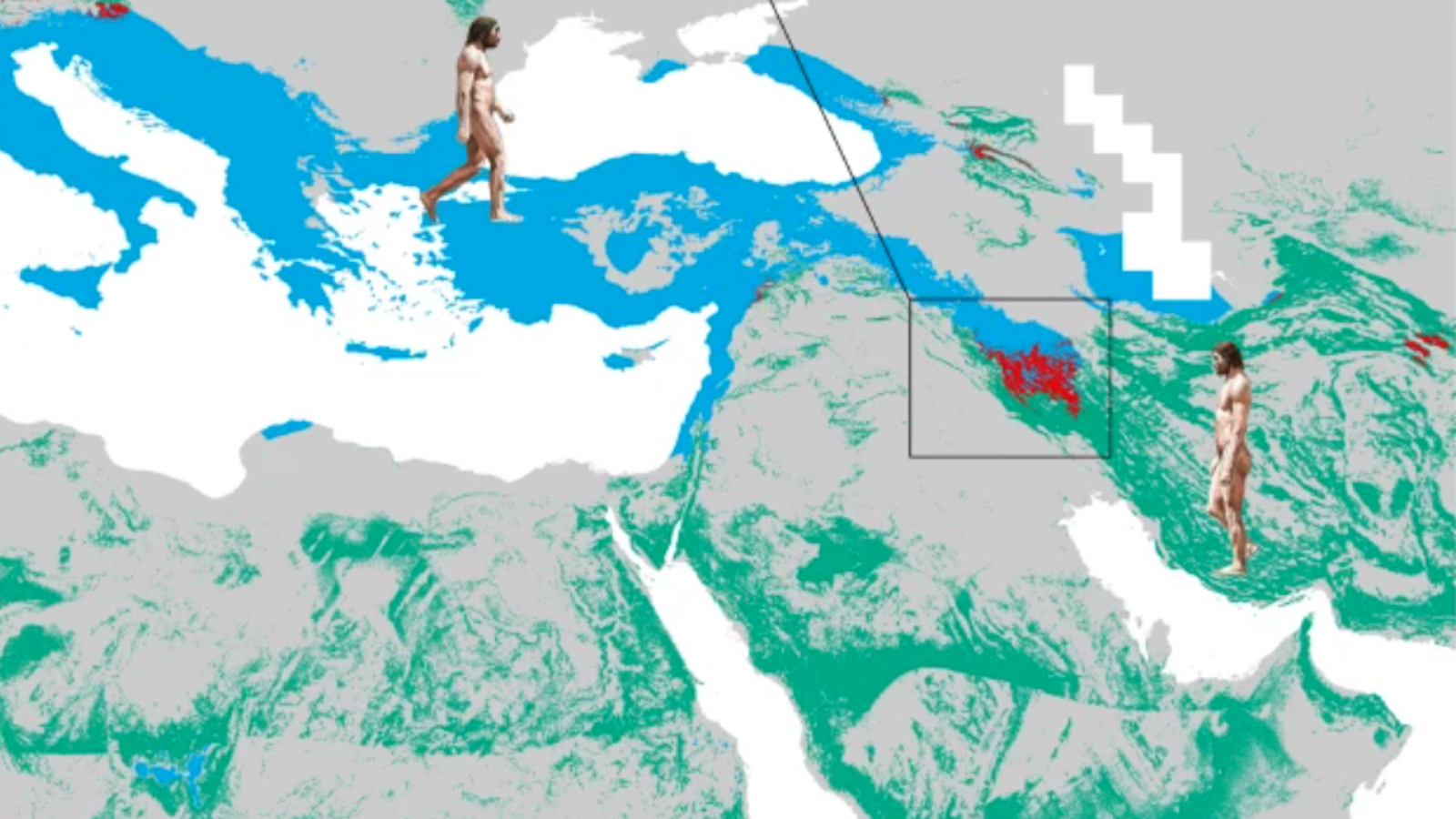

The challenge: Today, Homo sapiens are the only humans on Earth, but for millions of years, we shared the planet with other distinct human lineages, including Neanderthals and Denisovans.

This overlap makes it harder to piece together our history — when we discover new artifacts, we have to make assumptions about who they belonged to before we can try to use them to make sense of our past.

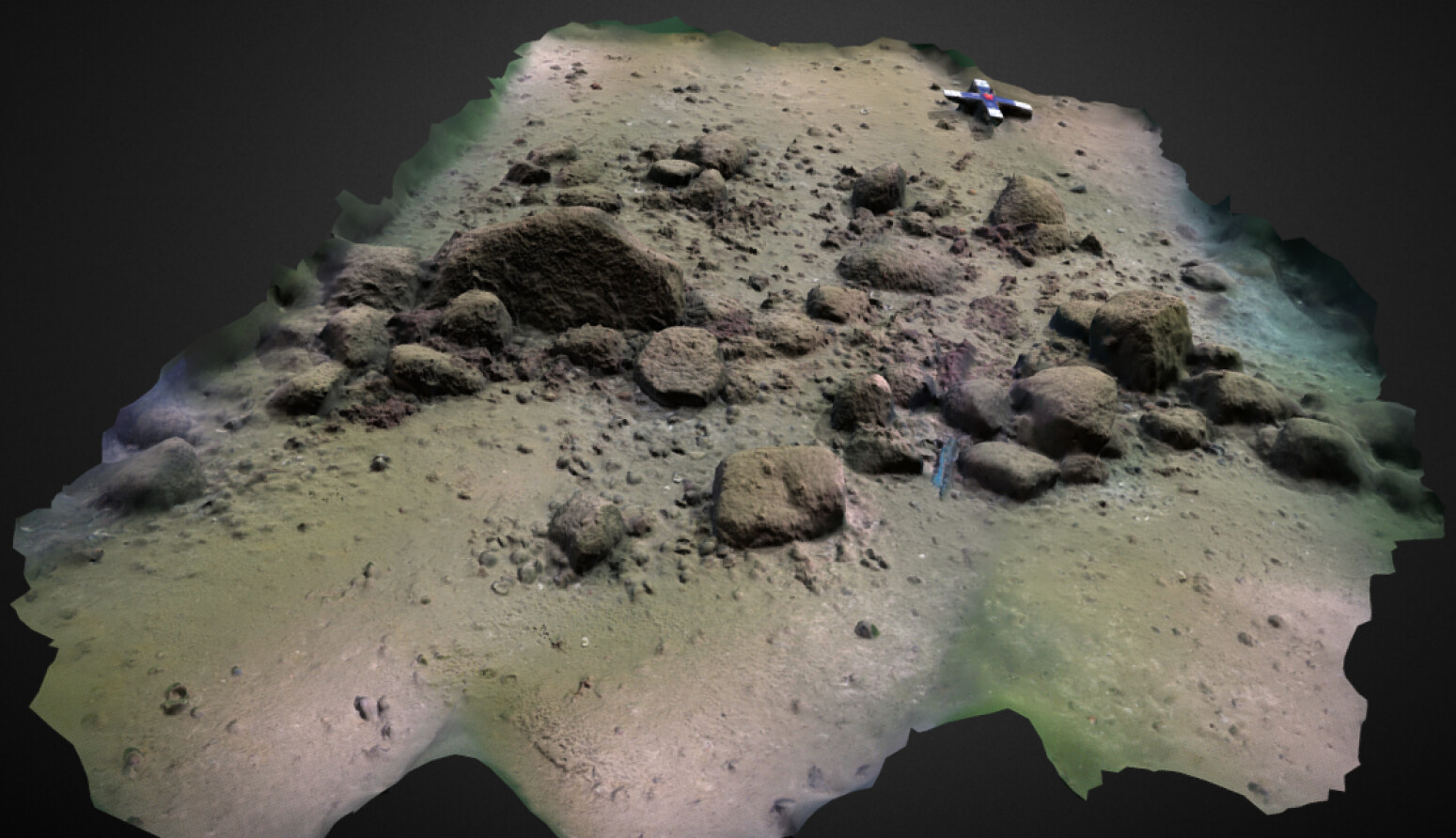

Mystery tools: In the 1930s, archaeologists explored a cave in Ranis, Germany, and discovered ancient stone tools they classified as belonging to the “Lincombian-Ranisian-Jerzmanowician” (LRJ) culture.

Tools from the LRJ culture have been found at several sites across northern Europe, and archaeologists suspected that Neanderthals had made them, but they were never sure.

Digging deeper: Between 2016 and 2022, an international research team re-excavated the Ranis cave, reaching parts of its interior that were inaccessible to the 1930s teams due to a large rock.

“After removing that rock by hand, we finally uncovered the LRJ layers and even found human fossils,” said Marcel Weiss from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology (MPI EVA). “This came as a huge surprise, as no human fossils were known from the LRJ before, and was a reward for the hard work at the site.”

The payoff: By the end of the excavation, the team had discovered 13 bone fragments, and using the latest DNA analysis tools, they determined that all 13 belonged to Homo sapiens. Radiocarbon dating, meanwhile, revealed that the bone fragments were 45,000 years old.

This suggests that “Homo sapiens made this [LRJ] technology, and that Homo sapiens were this far north at this time period, which is 45,000 years ago,” said co-first author Elena Zavala from UC Berkeley. “So these are among the earliest Homo sapiens in Europe.”

“This fundamentally changes our previous knowledge about this time period: H. sapiens reached northwestern Europe long before Neanderthal disappearance in southwestern Europe,” said Jean-Jacques Hublin from MPI EVA.

This article was originally published by our sister site, Freethink.