- The history of medicine and biology often has been embarrassingly wrong when it comes to female anatomy and was surprisingly resistant to progress.

- Aristotle and the ancient Greeks are much to blame for the mistaken notion of women as cold, passive, and little more than a “mutilated man.”

- Thanks to this dubious science, and the likes of Sigmund Freud, we live today with a legacy that judges women according to antiquated biology and psychology.

The story of medicine has not been particularly kind to women. Not only was little anatomical or scientific research done on women or on women-specific issues, doctors often treated them differently.

Even today, women are up to ten times more likely to have their symptoms explained away as being psychological or psychosomatic than men. Worryingly, women are 50 percent more likely to be misdiagnosed after a heart attack, and drugs designed for “everyone” are actually much less effective (for pain) or too effective (for sleeping) in women.

Are these differences real or imagined? And what can the history of female medicine teach us about where we are today?

A mutilated male

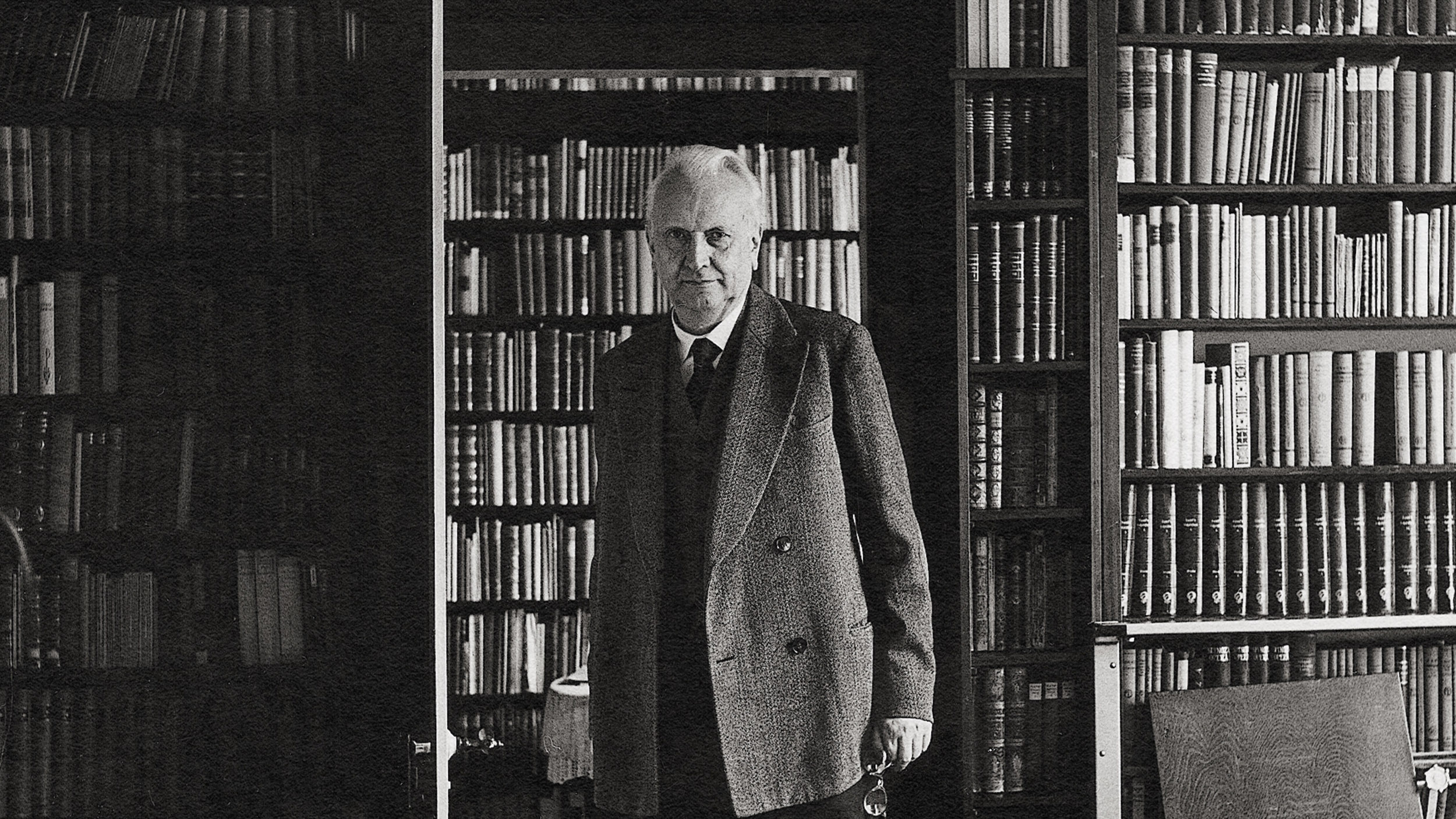

Aristotle is rightly considered one of the greatest minds of all time and is recognized as the founding father of many disciplines, including biology. He was one of the most rigorous and comprehensive scientists and field researchers the world had known. He categorized a large number of species based on a wide range of traits, such as movement, longevity, and sensory capacity. His views on women, then, stemmed from what he thought of as good, proper study. The problem is that he got pretty much all of it wrong.

According to Aristotle, during pregnancy, it was the man who, alone, contributed the all-important “form” of a fetus (that is, its defining nature and personality), whereas the woman provided only the matter (that is, the environment and sustenance to grow the fetus, which was provided by the menstrual blood).

From this, Aristotle extrapolated all sorts of dubious conclusions. He ventured that the man was superior, active, and dominant, and the woman inferior, passive, and submissive. As such, the woman’s role was to nurture children, run a household, and be silent and obedient — political and cultural manifestations of dodgy biology. If women did not provide a child’s form and nature, how important could they really be?

Given this passivity, Aristotle argued that the woman must be associated with other passive things, like being cold and slow. The man, being dynamic and energetic, must be hot and fast. From this, Aristotle concluded that any defects or problems in childbirth can only be due to the sluggishness of the female womb. Even the positive biological aspects of being female, such as greater longevity, were put down to this cold rigidity — a lack of metabolism and spirit. Most notorious of all, since Aristotle believed that female children were themselves the result of an incomplete and underdeveloped gestation, women were simply “mutilated males” whose mothers’ cold wombs had overpowered the warm, vital, male sperm.

Aristotle can still be counted as a great mind, but when it came to women, his ideas have not aged well in just how far they negatively influenced what came after. Given that his works were seen as the authority well into the 16th century, he left quite the pernicious legacy.

A wandering womb

But, how much can we really blame Aristotle? Without the aid of modern scientific equipment, physicians and biologists were left to guess about female anatomy. Unfortunately, the damage was done, and Aristotle’s ideas of a troublesome uterus became so mainstream that they led to one of the more bizarre ideas in medical history: the wandering womb.

The “wandering womb” is the idea that the womb is actually some kind of roaming parasite in the body, possibly even a separate organism. According to this theory, after a woman menstruates, her womb becomes hot and dry and so becomes extra mobile. It is transformed into a voracious hunter. The womb will dart from organ to organ, seeking to steal its moisture and other vital fluids. This parasitic behavior caused all sorts of (female only) illnesses.

If a woman had asthma, the womb was leeching the lungs. Stomach aches, it was in the gut. And if it attacked the heart (which the ancients thought was the source of our thoughts), then it would cause all manner of mental health issues. In fact, the Greek word for womb is “hystera,” and so when we call someone (often a woman) hysterical, we are saying that their womb is causing mischief.

The “solutions” or “remedies” for a wandering womb were as strange as the theory. Since the womb was supposed to be attracted to sweet smells, placing flowers or perfumes around the vagina would “lure” it down. On the flip side, if you smoked noxious substances or ate disgusting foods, it would “repel” the womb away. By using all manner of smells, you could make the womb move wherever you wanted.

The oddest “remedy” — and most male-centric of all — is that, since the wandering womb was said to be caused by heat and dryness, a good solution would be male semen, which was thought of as cooling and wet. And so, the ancient and highly inaccurate myth was born that sex could cure a woman of her “hysteria.”

A lingering problem

We live today with the legacy of this kind of thinking. Freud was much taken with the idea of “hysteria,” and although he did accept that men could be subject to it as well, he believed it was overwhelmingly a female problem caused by female biology. The woman, for Freud, is mostly defined by her “sexual function.” What Freud calls “normal femininity” (the preferred and best outcome) is defined by passivity. A woman’s ideal development is one which moves from being active and “phallic” to passive and vaginal.

Nowadays, Freud and Aristotle’s legacy lies in just how easily women are defined by their sexuality. Given that men and women, both, are equally dependent on their biology, it is curious how much more often women are reduced to theirs. The idea that women are more emotional or slaves to their hormones than men is still a depressingly familiar trope. It is an idea that goes back to the Greeks.

If we think biology is important to who we are (as it most certainly is), we ought to make sure that the biology is as good and accurate as it can be.

Jonny Thomson teaches philosophy in Oxford. He runs a popular Instagram account called Mini Philosophy (@philosophyminis). His first book is Mini Philosophy: A Small Book of Big Ideas.