Not just T. rex: Why do giant dinosaurs have tiny arms?

- Researchers recently reported the discovery of Meraxes gigas, a huge carnivorous dinosaur with tiny arms rivaling those of T. rex.

- Meraxes and T. rex lived millions of years apart and are not closely related. They evolved the small arms independently, suggesting that reduced forelimbs served an important function.

- Researchers propose several hypotheses for the short arms and highlight that skull size and arm length are inversely proportional among some dinosaurs.

The bizarre anatomy of Tyrannosaurus rex has drawn subtle mockery for years. With its enormous skull, massive teeth, and gigantic body, T. rex’s tiny arms just don’t seem to fit. Plus, they tend to deflate the menacing look that T. rex otherwise nails.

It bears the brunt of jokes, yet T. rex is not the only enormous carnivore with small arms. Many theropods, a clade of bipedal carnivorous dinosaurs, have small arms attached to a massive body. Examples include Carnotaurus, whose name means meat-eating bull and whose arms look like vestigial stubs. Carnotaurus is a member of the Abelisaurid family, which, just like Tyrannosaurus, is a group of theropods with small arms. Both groups lived during the late Cretaceous period, around 66 million to 68 million years ago.

Now, researchers can add another group to the mix. In a new paper in Current Biology, researchers led by Argentina’s Juan Canale report the discovery of a giant carnivorous dinosaur, Meraxes gigas. Meraxes is part of the Carcharodontosauridae, a family of dominant predators that inhabited most continents in the Early Cretaceous, 100 million million to 145 million years ago, long before T. rex was around. Like T. rex and Carnotaurus, Meraxes’ short forelimbs seem out of place with its colossal body.

The discovery provides evidence that reduced forelimbs evolved independently in separate groups of dinosaurs. Scientists still debate the purpose of the reduced forelimbs, but their appearance across different evolutionary branches is convincing evidence that the short arms served some function for these megafauna.

Unearthing the dragon

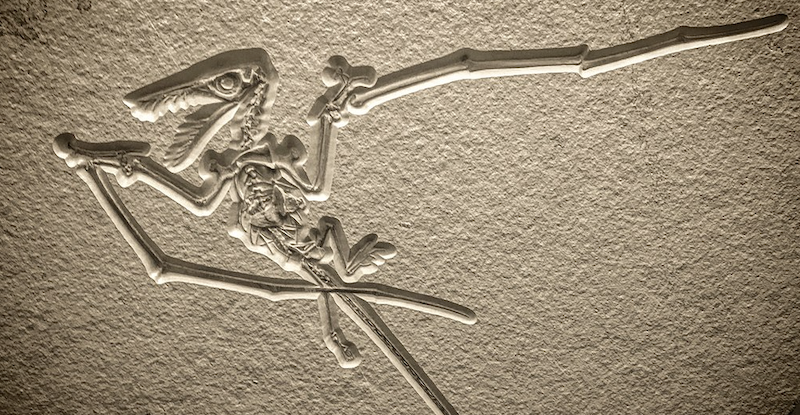

In 2012, on the first day of an excavation in Patagonia, scientists unearthed parts of Meraxes. They then spent a decade excavating and carefully analyzing the specimen. Having unearthed the most complete carcharodontosaurid skeleton ever found, Canale and his colleagues could give a detailed description of the dinosaur’s anatomy.

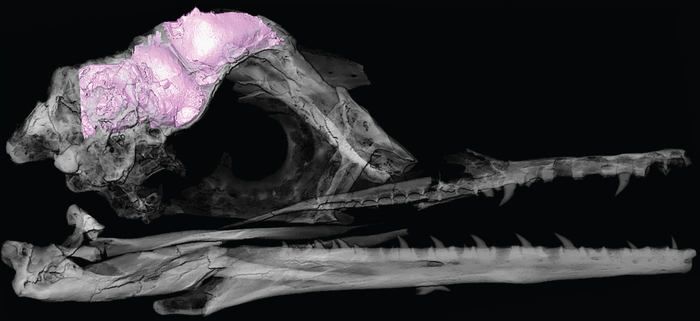

The genus name Meraxes refers to the name of a dragon in George R.R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire fiction series. The species epithet they gave it, gigas, is Greek for giant, and it is no exaggeration. With a 127 centimeter-long skull and a body weighing more than 4,200 kilograms, Meraxes was a beast. Still, it was not even the largest dinosaur in the area. Because the specimen’s cranium is almost complete, researchers used Meraxes’ skull to project the measurements of incomplete craniums from other dinosaurs. For example, using Meraxes as a scale, researchers estimate that its relative, Giganotosaurus, had a skull of some 162 centimeters in length, making it one of the longest theropod skulls discovered.

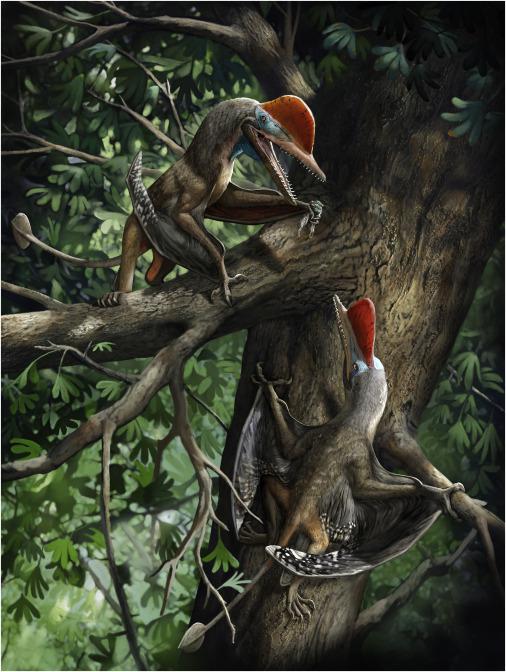

The Meraxes skull also had ornamented dermal bones with irregular vertical furrows and ridges, and a robust horn projecting from its brow. These facial features are unique to the species and suggest that the Carcharodontosaurids had a high diversity of facial ornamentation that probably served to attract mates.

The most notable feature of Meraxes is its nearly perfectly preserved forelimbs. The arms are only about half the length of the animal’s femur. Meraxes is the first dinosaur of its type found with preserved forelimbs, and the find suggests that tiny arms were a trait common to all Carcharodontosaurids.

A small pattern among large dinosaurs

The researchers found that Meraxes and Tyrannosaurus exhibited more remarkable similarities in arm length than would be expected under a model where the trait change happens randomly. In other words, the species’ fore-to-hindlimb ratios were too similar to be the product of chance, suggesting they evolved to carry out a similar function. This idea is supported by the probability that Meraxes and Tyrannosaurus inhabited similar ecological niches as the giant, meat-eating dinosaurs in their respective periods and areas. They probably had similar experiences and needs.

Still, Meraxes and Tyrannosaurus are not closely related, and Meraxes went extinct at least 20 million years before Tyrannosaurus showed up. Their similar arm anatomy is an example of convergence, which describes the independent evolution of similar traits in unrelated lineages. Convergent evolution typically occurs when distantly related groups of animals face similar biological or ecological hurdles. A classic example of a convergent feature is the development of wings, which independently evolved in birds, bats, and insects.

As more small-armed, huge dinosaurs are found, it becomes less likely that the arms had no function. Small arms must have been actively selected for in multiple lineages of giant predatory dinosaurs because they offered the creatures some advantage.

Why small arms?

The diminutive arms of Tyrannosaurus have fascinated researchers and the public for decades. The common notion argues that Tyrannosaurus did not use long arms, did not need them, and stopped directing resources towards their growth and development. Some researchers hypothesize that the animals used the small arms to hold mates close during reproduction, or to rise from a prone position. Others have proposed that the arms shrunk so they did not accidentally get bitten off during a feeding frenzy of dinosaurs trying to rip a piece of meat from a carcass.

Canale and co-authors use their analysis of Meraxes to support a fourth hypothesis: Small arms track the evolution of massive skulls. For example, other multi-ton carnivorous dinosaurs like Deinocheirus or Gigantoraptor have long forelimbs but small skulls. In this hypothesis, scientists suggest that the larger the skull, the more valuable it becomes for snatching prey. The arms then reduce as the skull takes over most, if not all, predatory functions.

Still, the authors point out that the musculature of the arms suggests they were far from a useless, vestigial limb. The truth could lie in the intersection of the various hypotheses proposed. Whatever the reason, because scientists will never be able to directly observe the behavior of a theropod with small arms, the mystery will continue to endure and tease at our imaginations.