How Christianity conquered Rome through simple math

- An enduring myth is that Constantine the Great Christianized Rome after receiving a vision in 312 AD.

- However, historian Bart Ehrman argues the religion’s growth rate ensured Christians would account for half the Empire’s population by 400 AD anyway.

- This resulted from two features unique to Christianity among religions at that time: It was exclusionary and evangelistic.

In 312 AD, Constantine the Great confronted his rival for the imperial throne, Maxentius. By all accounts, Constantine’s campaign was doomed. Maxentius not only boasted a superior force but also control of Rome itself. However, before the battle, Constantine received a vision. He saw in the sky the shape of a cross burning with light. Inscribed upon it were the words “By this conquer.”

After consulting his spiritual advisors, Constantine ordered a golden cross built and marched his army with it as his standard. The battle was decisive. His forces swiftly broke through Maxentius’ cavalry and then his infantry, pushing the stunned soldiers into the Tiber River where they were slaughtered. In appreciation of his holy benefactor, Constantine converted and set the Roman world on the path toward Christianity. (That’s one version of the story, at least.)

Many see the conversion of Constantine as the effective end of paganism, but in many ways, it merely represented the culmination of underlying social trends that had been brewing for centuries. By 300 AD, there were already millions of Christians across the Empire, with some (likely high) estimates claiming the religion accounted for 10% of the population. By the century’s end, they would account for 50%.

But how? How did a small Jewish sect from the imperial sticks grow to dominate the world’s most powerful empire in a few short centuries? Some may argue it was by kingly decree, others the will of God. But according to biblical scholar Bart Ehrman, who specializes in early Christianity, we need neither the romantic nor the miraculous to explain the history of Christianity’s triumph. Some simple math will do.

Working mathematical “miracles”

In the Book of Acts, Peter the Apostle delivers a sermon on the day of Pentecost. Thanks to the power of his oration, Peter converts 3,000 people to the faith. A few chapters later, he converts another 5,000. A chapter after that, “multitudes” more. And the “Lord added to the church daily as should be saved” (Acts 2:47b).

Stories like these are common in the Bible, but there are a few problems. First, we have little reliable evidence of mass conversions. Second, at such remarkable rates, Christianity would have become a political and cultural powerhouse well in advance of the 4th century AD. For instance, estimates of Jerusalem’s population at the time of Peter’s sermon range from 20,000 to 75,000 people, meaning the apostle converted anywhere from a sixth to half the city over a long weekend. Unlikely.

It wasn’t just Christian authors either. In the Annals, the historian Tacitus claims that Emperor Nero found “an immense multitude” of Christians guilty of the Great Fire of Rome in 64 AD. But as Ehrman points out, “If Christianity were such a large threat at this stage of imperial history, we simply cannot explain why most Roman authors have little or, more frequently, absolutely nothing to say about them.”

These examples point to the challenges of using ancient sources to determine how many Christians lived in certain regions at certain times — namely, people often exaggerate to strengthen their ideological or political views. But just as sociologists have ways of cutting through the modern hyperbole surrounding, say, inauguration crowd sizes, so too do historians have strategies for sussing out a more realistic picture of the past. In the case of Christianity, we can substitute miracles and sinister cabals for a steady growth rate.

Ehrman asks us to assume there were 1,000 Christians in the Empire by 60 AD. At a rate of growth of roughly 40% per decade, there would be between 7,000 and 10,000 Christians by the year 100. In other words, of that initial 1,000, every 100 Christians would only need to convert 3 or 4 people to the faith every year. Not an ungodly sum — especially for a religion that places such importance on evangelism (as we’ll see).

At that rate, you get the following breakdown as taken from Ehrman’s book The Triumph of Christianity:

- 30 AD: 20 Christians

- 60 AD: between 1,000-1,500 Christians

- 100 AD: between 7,000-10,000 Christians

- 150 AD: between 30,000-40,000 Christians

- 200 AD: between 140,000-170,000 Christians

- 300 AD: between 2.5-3.5 million Christians

- 400 AD: between 25-35 million Christians

“To non-statisticians, these raw numbers — especially toward the end of the chart — may look incredible. But in fact, they are simply the result of an exponential curve,” Ehrman writes.

Math savvy readers will notice that this is the same principle governing compound interest. You invest a little money and receive some interest. Soon, you’re not only earning interest on the initial principal but also interest on your interest. This compounding effect grows your investment at an accelerated rate. In the same way, a person converted today can proselytize next year and the year after, bringing new members into the flock who, in turn, can bring in even more.

Those same readers may also notice that Ehrman’s numbers don’t perfectly align with a 40% per decade rate. That’s because Ehrman is trying to take the complex realities of history into account.

As attested by surviving Christian letters, for example, the religion must have experienced a conversion boom early on (hence the jump from 20 Christians to 1,000 in 30 years). The rate of growth also had to slow down by 300 AD — ironically around the time of Constantine — or else Christianity would have overtaken the entire population of the Empire by the century’s end, which obviously didn’t happen. Even so, the math shows that, in principle, Christianity could have amassed enough followers to be the dominant political and cultural force in Rome by 400 AD — with or without Constantine.

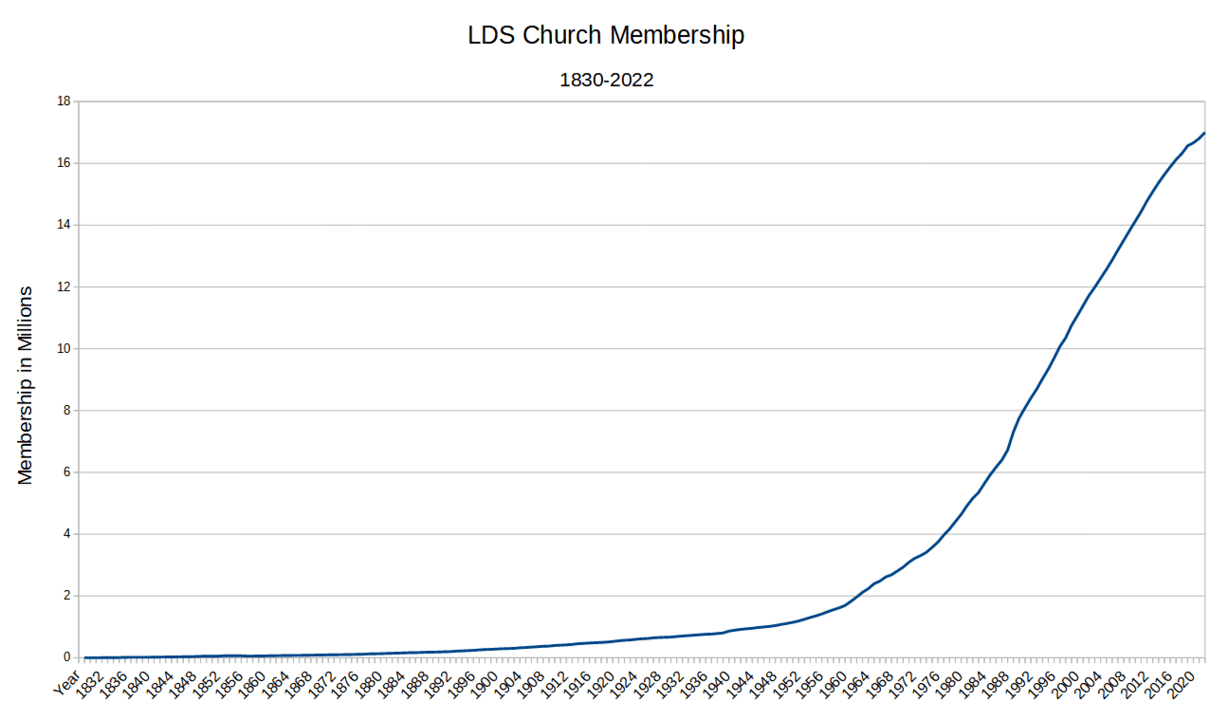

“Christians may well want to claim it was a miracle, that it was ultimately God’s doing. The historian has no way of evaluating that claim. But the triumph of Christianity would not have required supernatural intervention. It would have required a steady rate of growth,” Ehrman writes. In fact, Erhman adds, Christianity is hardly alone. A more contemporary analog to this ancient phenomenon is the Mormon Church. In its early years, Mormonism spread with viral efficiency, and recently conversion rates have slowed. However, on average, Mormonism has grown at a steady rate of — eerily enough — about 40% per decade, from just six members in 1829 to more than 16 million by 2020.

Evangelism as an innovation

That may explain how Christianity could grow so rapidly, but it doesn’t explain why. After all, couldn’t pagans use their home-field advantage to simply out-compete Christians at their own conversion game?

There are many theories as to what attracted ancient people to Christianity. Some claim paganism was on the decline already or that Christianity offered better healthcare. However, Ehrman argues that the appeal of Christianity centers on two key features: It was exclusionary and evangelistic.

While pagans certainly could worship a favorite god with zeal, they weren’t required to devote themselves to any specific one. A pagan could beseech the god Apollo today for one divine favor and then the goddess Diana tomorrow for another. So long as the proper prayers were recited and rites enacted, the gods didn’t care so much. (It’s all in the family after all).

Christians lacked this pluralistic view of the cosmos. Their god wasn’t one choice among many; theirs was the only God worthy of piety. He was also a jealous God. If he caught you worshiping elsewhere, he wouldn’t only punish you. He would punish your children and your children’s children for generations (Exodus 20:5).

Enter evangelism. While it may seem an obvious religious feature today, in the ancient world, it proved quite innovative. Paganism’s live-and-let-live tolerance toward other gods made evangelism kind of pointless. Additionally, there was no real incentive to convert. The gods weren’t keeping a soul tally, and unless someone majorly screwed up, the afterlife would prove remarkably egalitarian — assuming a belief in the afterlife at all.

Not so in Christianity. Its apocalyptic worldview claimed the end of the world was coming and soon. As Jesus preached, “There be some standing here, which shall not taste of death, till they see the Son of man coming in his kingdom.” (Matthew 16.28). When the end came, God would bless his followers with eternal life in his kingdom. Anyone outside the faith would be punished for eternity. What kind of punishment? Depends on which ancient apocalypse you cite. But trust us; it’ll be bad.

If Christians truly were to love their neighbors as themselves, as Jesus also preached, then surely they would want them to enjoy the fruits of paradise for all eternity. As such, conversion was a matter of paramount importance. But instead of mass conversions, Christians spread the Gospel through social networks and word of mouth — a few neighbors, coworkers, and family members at a time. This changed the math of religious life in the West. Faith became a zero-sum game. Every Christian convert was one fewer pagan in the world, and this slowly, but surely, bled paganism.

The triumph of Christianity

Of course, Rome’s Christianization entails much more history than can be covered here. There’s Paul’s ministry to the Gentiles, the importance of miracle stories, and the forming of the Christian orthodoxy under Emperor Theodosius I (all of which Ehrman and other historians discuss at length in their works).

None of this is to say that Constantine didn’t play an important role in that history. His conversion made it acceptable — and financially rewarding — for the powerful and prestigious to join the congregation. He gifted the church extravagant amounts of money and land, and headed construction projects such as the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem. He even founded the city of Constantinople (now Istanbul, not Constantinople) as Rome’s new eastern capital and a Christian city.

“But it would be a mistake to think that it was Constantine’s conversion alone that facilitated the Christianization of the empire. If Christianity had simply continued to grow at the rate it was growing at [the time] of the emperor’s conversion — or even less — it still would have eventually taken over,” Ehrman writes.

It’s a helpful reminder that history isn’t just a story about great men and decisive moments. Often, it’s about ordinary people doing what people do and, in the process, transforming the course of history.