How eccentric religions were born in 19th-century America

- The freedoms of America’s new democracy seeded a hotbed of social and religious experimentation.

- The widespread popularity of 19th-century newspapers gave nonconformists a platform for their ideas.

- Whether religious or secular, most utopian communities crashed and burned.

Newspapers were a thriving business in the 1830s. There were twice as many of them in America as there had been in 1810. Alexis de Tocqueville, a French aristocrat who traveled the young country in 1831, was amazed at the number of periodicals. Every village, he reported, had a newspaper, and the power of the press was impressive. John Humphrey Noyes — God’s self-anointed messenger — planned to launch a religious newspaper that would serve as the pulpit of the world.

As early as 1834, he had published a monthly in New Haven called The Perfectionist. It quickly attracted more than five hundred subscribers. Three years later, he launched a new paper, The Witness, in upstate New York, but he distributed only a few issues. Now, back home in Putney, Vermont, he and his wife, Harriet, planned to ignite a new religious revival through the printed word.

Noyes recruited three of his eight siblings to help with the publication and attracted a small coterie. Within five years, he had more than thirty disciples, who drafted and signed a “Statement of Principles”: “John H. Noyes,” they pledged, “is the father and overseer whom the Holy Ghost has set over the family thus constituted. To John H. Noyes … we submit ourselves in all things” — including carnal relations.

Two followers, Mary and George Cragin, agreed to join John and Harriet Noyes in a group marriage. Other converts soon followed their lead. Although the arrangements were an open secret, townspeople in Putney were outraged after Mary Cragin gave birth to Noyes’s twins — Victor and Victoria — and authorities learned about the group’s conjugal customs. In October 1847, Noyes was arrested and charged with adultery and fornication. Fearing mob violence, he fled the village.

Weeks later, he found refuge in central New York, with a follower named Jonathan Burt. The owner of a sawmill on Oneida Creek, Burt had read about and passionately embraced Noyes’s theology. He invited the Putney group to settle on land adjoining his forty acres of fields and woodland. The property, once owned by the Oneida Tribe, had a barn and a primitive cabin on twenty-three rolling acres. Noyes purchased the land for five hundred dollars and summoned his devoted band.

Charismatic leaders filled the void with new, imaginative social structures.

On an icy March day in 1848, his wife, Harriet, and Mary and George Cragin arrived by train at the Oneida depot. Blasted by the biting wind, the three disciples gazed out at a bleak landscape of barren snowdrifts and bare trees. Soon, bundled into open sleighs, they made their way across frozen fields, where they would transplant the seeds of their new religion.

They were not the first to find fertile prospects in upstate New York. It was a hotbed of eccentric theology. In 1776, an Englishwoman named Ann Lee had settled near Albany with a few followers. She claimed she was the female embodiment of a bisexual God, and her disciples committed to complete celibacy. The sect, known as the Shakers, grew from nine original members to six thousand by the 1840s.

In 1823, in Palmyra, New York, a teenage treasure hunter named Joseph Smith claimed he had found golden plates inscribed with the true gospel. He later alleged that he had translated their hieroglyphics into The Book of Mormon and founded a new religion based on local New York legends about a pre-Indian race and the radical practice of polygamy.

Rochester, New York, was the hub of a massive movement founded by William Miller. In 1831, Miller, a Baptist preacher, declared that the world would end in 1843, a prediction widely promoted in a newspaper called Signs of the Times. Thanks to an aggressive publicity campaign, as many as a million Americans were waiting for the ecstatic moment when the wicked would burn up and God’s children would fly into the sky to meet the Lord. Believers were said to abandon their crops, shut their businesses, and wait for the rapture in white ascension robes. The frenzy of anticipation was so great that the New York Tribune published a special issue refuting Miller’s predictions. The American Journal of Insanity warned that thousands of American citizens had become deranged.

After 1843 came and went without the rapture, Miller revised his calculations and declared that the world would end, instead, on October 22, 1844. On October 21, disciples climbed trees and hills to be closer to heaven, but they were still earthbound on the twenty-third. The celestial flop, known as “The Great Disappointment,” was reported in papers around the country. Believers had been “up a few nights watching and making noises like serenading tom cats,” wrote the Cleveland Plain Dealer, before they gloomily gave up and went to bed.

Religious fever

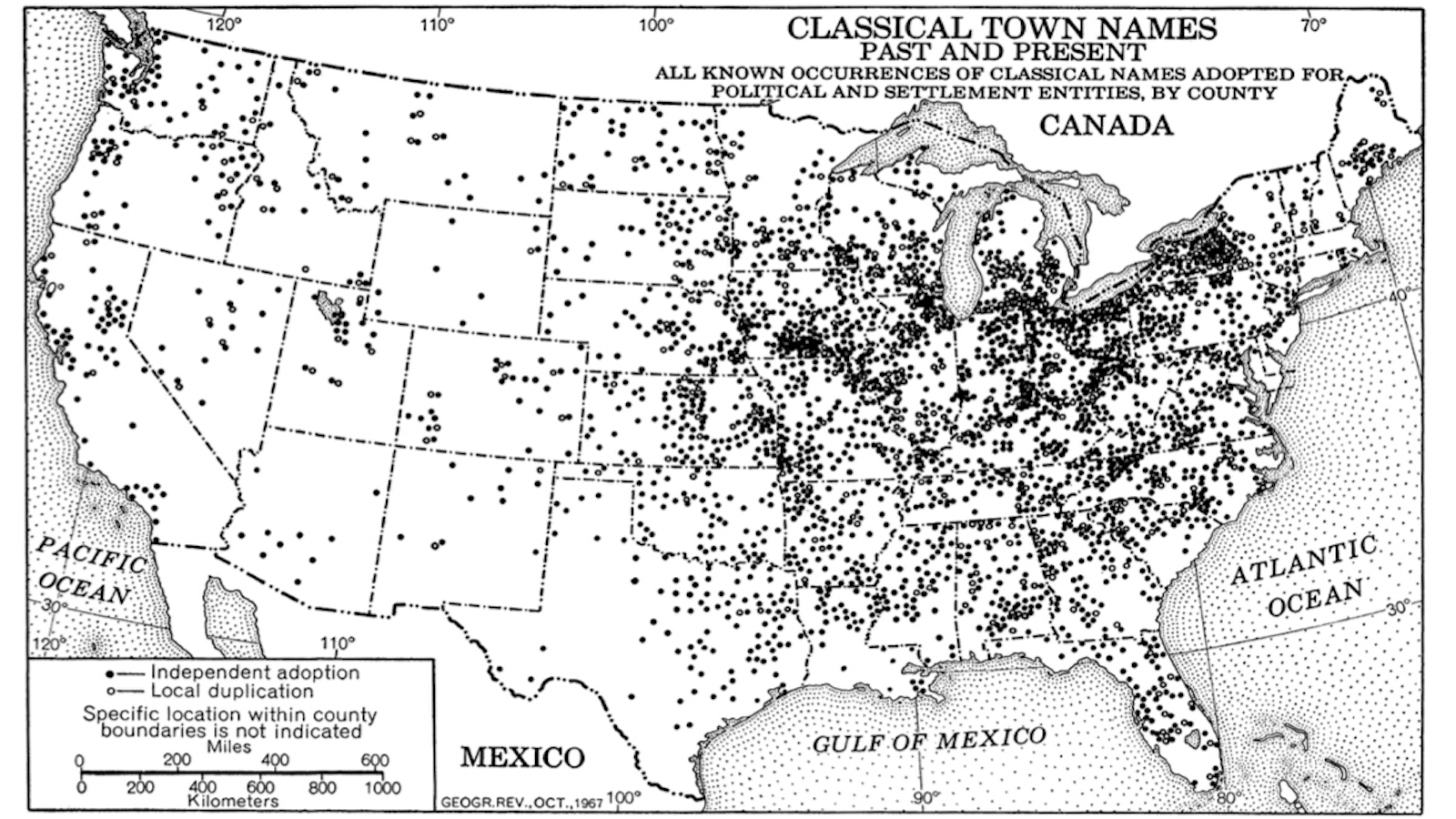

The region was so aflame with religious fever that it was later called the Burned-Over District. But social and religious experiments had bloomed across the country after the War for Independence. The revolution had shattered institutions and traditions. Charismatic leaders filled the void with new, imaginative social structures. In America’s new democracy, any man could do pretty much as he pleased, declared the New York Tribune’s founder, Horace Greeley. The individual was the world, said philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson, and almost every reading man had “a draft of a new community” in his pocket. Inspired by faith in freedom and divine revelation, Americans launched more than seventy utopian experiments between 1800 and 1860.

Some, like New Harmony, Indiana, were secular communities. Founded by a Welshman named Robert Owen in 1825, New Harmony was formed “to promote the happiness of the world” through communal benefits and cooperation. In its first weeks, eight hundred people joined the community, but by 1828, New Harmony was divided into fighting factions and dissolved in discord. Other utopias, like the Kingdom of Matthias, promised disciples divine salvation. Its founder, Matthias, was a carpenter named Robert Matthews. In the early 1830s, he announced that he was God the Father and Jesus Christ. He strolled Manhattan in a coat embroidered with silver stars, carrying a great key to the gates of paradise. Matthias soon moved into a follower’s mansion in Westchester, New York, where he attracted a community of devoted converts. In a ritual called the “Fountain of Eden,” members of his kingdom would surround him, naked, in a circle while Matthias sluiced them with a sponge and declared them virgins.

The spirit of the age was singularity. As Emerson urged, “A man must be a nonconformist.” Life in America in the early nineteenth century was a grand experiment in which every man, he wrote, could build his own world.