Why you should be like a drunken monk and party like it’s 1399

- Festive celebrations are essential for relieving stress, positively impacting mood, and strengthening interpersonal relationships.

- In the Middle Ages, carnivals inverted societal norms and created spaces for joy, freedom, and self-expression in a typically oppressive world.

- According to philosopher Mikhail Bakhtin, reintroducing the spirit of such unrestrained celebration in modern society can help manage existential anxieties and establish "true human fearlessness."

Sometimes, you just need to party. When you’ve had one of those weeks — where everything is a chore and nothing comes easily — it feels good to put a stop to it with a big weekend. If you’ve had a stressful and impossibly long day, the perfect balm can be a busy bar full of riotous laughter and clinking glasses. During the long, cold, flowerless winter, an indulgent midwinter feast might be precisely what you need.

Such festivities are not just self-indulgent. Research suggests they can be a form of self-care. For example, people who listen to live music have been shown to be better at “‘managing their moods, self-identity, and interpersonal relationships.” It also has been found that people are more prosocial after a celebration. When we eat and drink together, while celebrating something positive, we strengthen our communal bonds by making people more caring toward each other. And according to one 2017 study, festivals “not only contribute to a transitory state of subjective well-being, but can also become part of the way a person defines themselves.”

However, for the Russian philosopher Mikhail Bakhtin, it isn’t enough that we have a blow out once in a while. We also need to make sure we party the right way.

Silly hats and live music

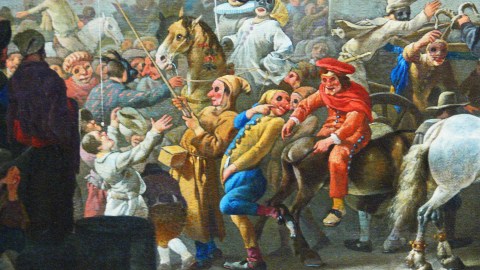

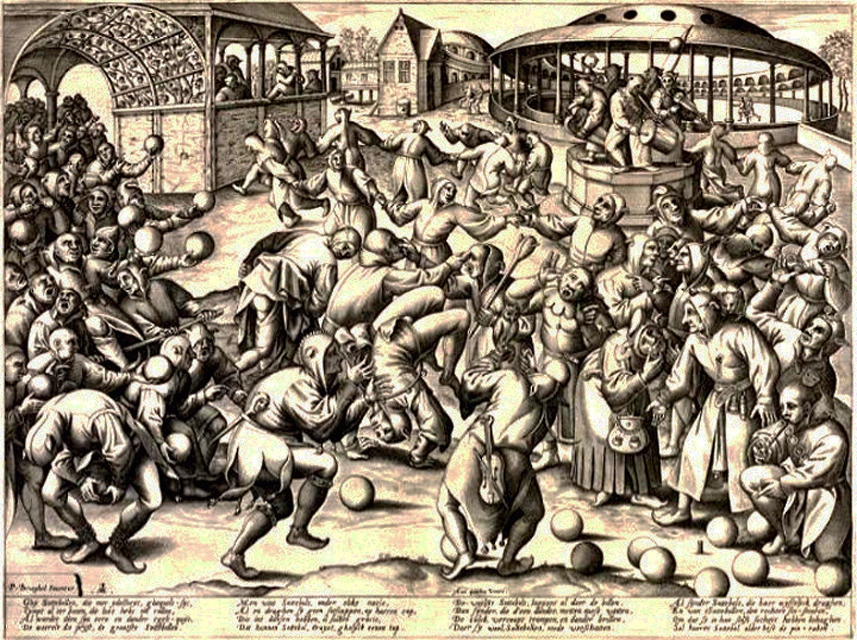

In medieval times, parties were often called “carnivals.” But carnivals were not simply drunken nights with fist fights and sweaty dancing. They came with important symbolic value.

Carnivals were about the inversion of values, a way of turning the world upside down — with the first being last, and the top being bottom. Bishops would dress in lewd clothes, kings as jesters, and local lords as grotesque monsters. Carnivals were a way for the folk (the narod) to express themselves, and this vibrant manifestation of the folk-spirit brought the overbearing down to earth. In an age of asceticism, intimidation, and oppression, the carnival was debauchery, happiness, and freedom.

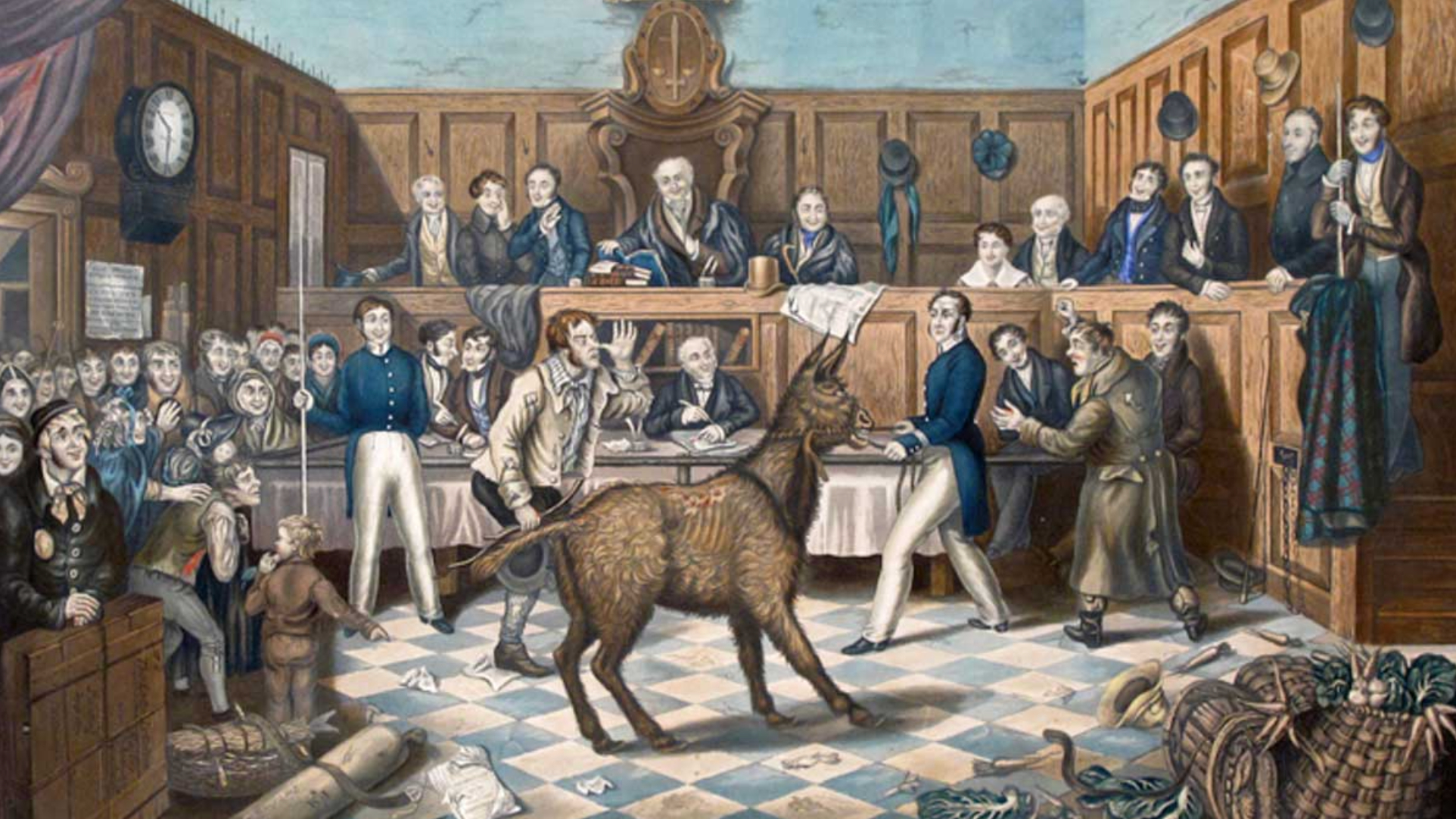

The Feast of Fools

History is full of Bakhtin-type carnivals. You only have to look for a somber religious ceremony to find an accompanying and highly absurd booze up soon after. Twelfth Night in Europe, Holi in India, the Hungry Ghost Festival in China, and the Gede Festivals in Haiti are all examples of excessive, iconoclastic revelry. But there’s one example that stands out: the Feast of Fools.

The Feast of Fools was an event celebrated in France around the New Year, and it was all about satire and frivolity. It involved role reversal (where the lower clergy would dress as bishops and vice versa) and mock ceremonies. There was crossdressing and drunkenness. Often, a “Lord of Misrule” or “Fool’s Pope” was elected for the day, usually from poorer parts of society. The Lord of Misrule would prance around causing all sorts of good-natured mischief.

Of course, not everyone was keen on the Feast. In 1445, the Theology Faculty of Paris sent an angry letter to the bishops of France. It read:

“Priests and clerks may be seen wearing masks and monstrous visages at the hours of office. They dance in the choir dressed as women, panders [pimps], or minstrels. They sing wanton songs. They eat black puddings at the horn of the altar while the celebrant is saying mass. They play at dice there. They cense with stinking smoke from the soles of old shoes. They run and leap through the church, without a blush at their own shame. Finally, they drive about the town and its theatres in shabby traps and carts; and rouse the laughter of their fellows and the bystanders in infamous performances with indecent gestures and verses scurrilous and unchaste.“

That all sounds like quite a lot of fun.

One more song!

Today, it can feel like we have lost the spirit of carnival. We get drunk and go dancing, but there’s no revelry. There is no mocking of the world where we make light of dark things. For Bakhtin, the carnival should be a frenzied celebration of life, one which makes those great terrors of existence — time, sickness, and death — feel less frightening. We should party hard and party long to combat the dread of everyday life and re-establish what Bakhtin calls “true human fearlessness.” In pantomime, parodies, and a laughter so loud it borders on the insane, we make life’s fears ridiculous.

So, perhaps it’s time for a binge. Maybe we should put on pause the safe and healthy proscriptions of an anodyne age and go on a thirsty rampage. In the drunken swirl of the carnival trance, the terrifying gravity of life is made lighter.