How people crossed the Atlantic Ocean before commercial aviation

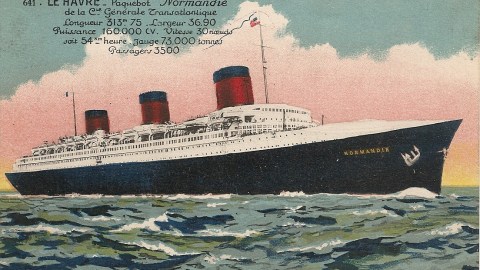

- Before planes, giant steam ships carried immigrants and travelers between Europe and the Americas.

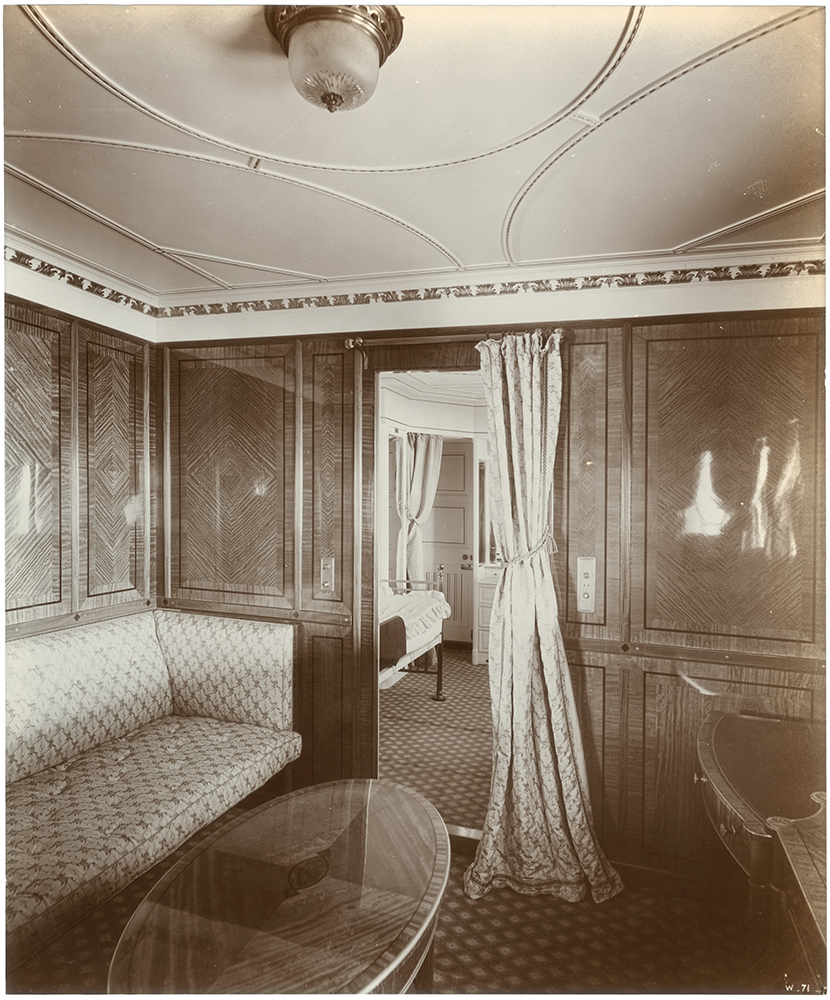

- Aboard, your travel experience could vary drastically depending on your income and social standing, with first-class tickets providing access to unimaginable luxuries.

- The commercial ocean travel industry dwindled after World War I, which left people weary of interacting with foreign countries.

The 2014 documentary series I was a Jet Set Stewardess by the Smithsonian Channel recounts a bygone time when traveling by airplane was a glamorous experience, even when you rode economy class. Today, commercial air transport is anything but. After American president Jimmy Carter signed the Airline Deregulation Act in 1978, igniting a price war, cocktail parties and seven-course meals gradually made way for peanuts, pretzels, and overpriced beer. Where travelers used to board planes wearing their Sunday best, now they prefer to fly in sweatpants and worn-out t-shirts.

The extravagance seen in Jet Set Stewardess echoes another earlier period in the history of cross-continental travel. Long before Orville and Wilbur Wright managed to take to the skies, people were traveling back and forth between Europe and America by ships. The commercial ocean travel industry emerged in the 1870s. Its development was spurred in part by the American Civil War, which saw the introduction of new technologies to move men and military supplies across the country’s coastlines.

As Mark Rennella and Whitney Walton explain in “Planned Serendipity: American Travelers and the Transatlantic Voyage in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries”:

“After 1865 ships clad in iron and steel, following the prototype of the battleships Monitor and Merrimac developed to batter the fragile hulls of wooden sailing ships, grew in size, strength, and safety to transport ever-increasing numbers of goods, immigrants, and tourists between America and Europe, as well as other distant parts of the world.”

Safety was perhaps the biggest concern for travelers. Prior to the Civil War, as many as one in seven vessels were lost at sea. By the end of the century, the risk of getting shipwrecked decreased significantly. This was, as Rennella and Walton indicate, largely due to the invention of new technology. Aside from the introduction of steel hulls and cabins, ships were now fitted with gyroscopic stabilizers and anti-rolling tanks to prevent capsizing, and submarine signalers capable of detecting submerged hazards like icebergs.

These new technologies not only made journeys across the Atlantic Ocean safer, but also quicker. In 1838, the world’s fastest steamer, the SS Sirius, traveled from Cork to New York City in just over 18 days. In 1863, a few years before the end of the Civil War, the RMS Scotia completed the same journey in eight days. One of the most extraordinary records was set by the RMS Lusitania. In 1907, the Lusitania traveled from Queenstown to Sandy Hook in four days and 19 hours. Companies were always trying to set new records in order to attract customers.

Crossing the Atlantic Ocean

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, more people traveled from Europe to the Americas than the other way around. According to Thomas Page, the author of The Causes of Earlier European Immigration to the United States, the driving factors behind immigration from 1820 to I875 “fall into two groups: those that repelled from the mother country and those that attracted to the United States.” Crop failure, land shortages, unemployment, war, and persecution left many Europeans hoping to start a better life in the New World.

A considerable majority of these immigrants began their journey in Liverpool, at the time the continent’s biggest harbor. Its granite docks, which Moby Dick author Herman Melville compared to the pyramids of Egypt in both their size and stature, served as the headquarters of the Cunard Line as well as the White Star Line, two of the biggest players in the commercial ocean travel industry.

Ships that disembarked from Liverpool usually set sail for New York. At the beginning of the 20th century, over 30% of the city’s population consisted either of immigrants or the children of immigrants. After passing the Statue of Liberty, travelers stepped onto double-decked piers where dockworkers unloaded cargo and merchants sold wares in Polish and Italian.

While Europeans traveled to the Americas in search of work and a new home, Americans – albeit in smaller numbers – were traveling to Europe for recreational purposes. Wealthy citizens went on world tours to “broaden their consciousness” and forget the hardships of the Civil War. Artists flocked to France in search of inspiration. Businessmen, policy makers, and academics trekked across the continent to meet with and strengthen international relations. “Everybody was going to Europe,” attested the American author Mark Twain in 1867. “I too, was going to Europe – the steamship lines were carrying Americans out of the various ports of the country at the rate of four or five thousand a week.”

To American vacationers, the Old World was as alluring as the New World was to European immigrants. In Planned Serendipity, Rennella and Walton quote the diary of one Sally Johnston, a Holyoke College student who journeyed to Europe on the SS Paris in 1938. Like everyone else on board, Johnston woke up at 4:30 AM to watch the ship pull into Plymouth Harbor. “We stayed up on deck for ages,” she wrote, “freezing to death, but watching the sunrise come over the hills of the harbor. It was very lovely and being very cold the whole thing was well worth the lack of sleep.”

All aboard

While at sea, your travel experience could vary drastically based on your wealth and social standing. Penniless immigrants on their way to the New World typically rode steerage class, where entire families were stuffed into small, windowless compartments. They slept in bunkbeds stacked atop each other and subsided on gruel served in equally crowded mess halls.

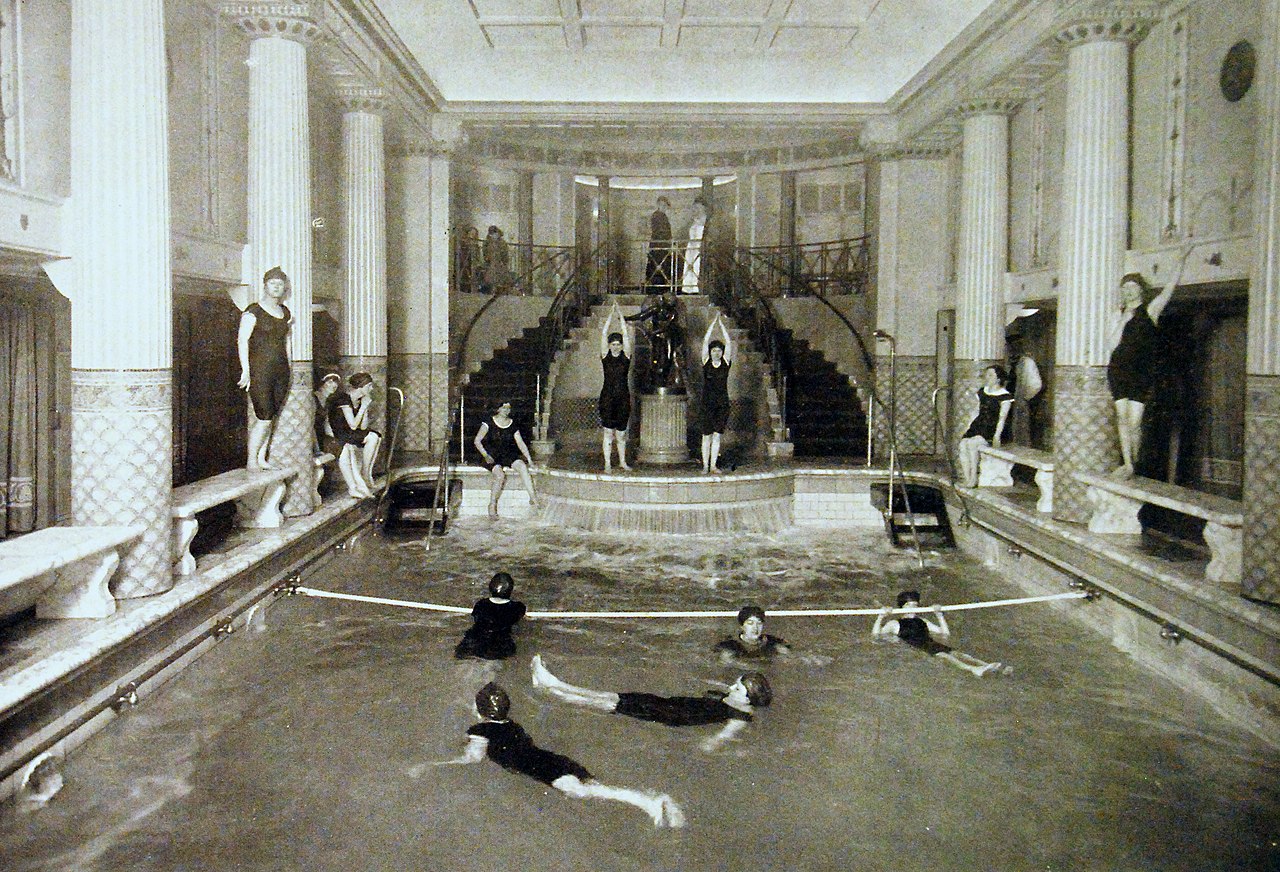

The differences between steerage class and first class were striking, even by today’s standards. First-class passengers slept in spacious suites. They ate in marble dining rooms beneath domed ceilings made from glass. Many restaurants, like the Ritz-Carlton on the SS Amerika, allowed passengers to dine at whatever time they wished, rather than at fixed hours. After dinner, first-class passengers could retreat into smoking rooms designed to look like Italian palazzos or bars resembling French mansions. The RMS Adriatic, owned and operated by Liverpool’s White Star Line, went the extra mile by fitting their ship with a Turkish bath and a floating swimming pool.

As with commercial air travel in the late 20th century, fierce competition between Cunard, White Star, and other lines gradually drove down the price of crossing the Atlantic Ocean, making them more affordable as time went on. In 1860, the cost of a one-way steerage ticket from America to Britain was 17 pounds, or just over 76 pounds in today’s terms. Three years later, prices dropped to 13 pounds, followed by nine pounds in 1883. According to Rennella and Walton, the cost of a Atlantic Ocean voyage during this time was comparable to that of a bike — then the most coveted luxury item in the US.

Impact of World War I

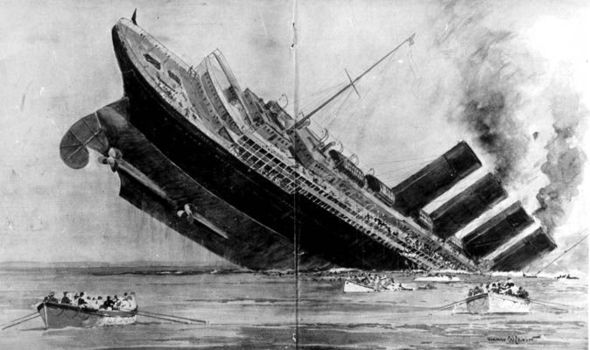

The commercial ocean travel industry, which had flourished after Union forces defeated the Confederacy, came to an end during the First World War, a time when governments on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean seized cruise ships and turned them into troop carriers and hospital ships using ports as military pickup points. Ocean lines that remained in business struggled financially as voyages became increasingly dangerous due to naval mines and German U-boats, one of which sank the Lusitania in 1915.

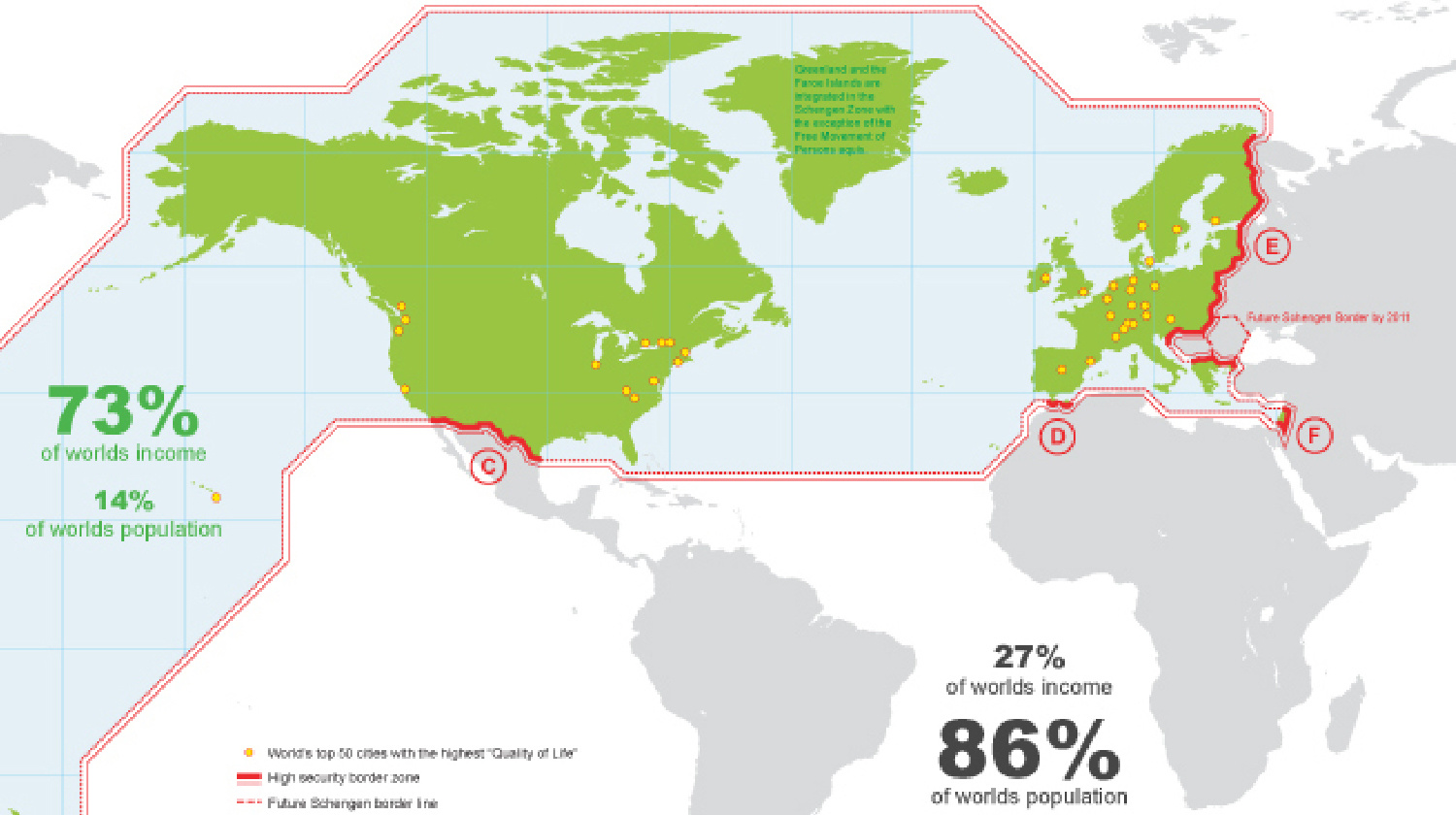

According to World Economic Forum, first-class journeys from Europe to America had fallen by more than 70% in 1913, while steerage arrivals fell by over 90%. After the war, the commercial ocean travel industry never recovered, partly because the global economy had been too badly damaged and partly because the fighting had rendered people fearful of visiting foreign countries. Despite efforts from Woodrow Wilson and his League of Nations, the United States withdrew into cultural as well as political isolationism. The American people came to regard foreigners “with great suspicion,” as the WFE puts it, and called for restrictions on international migration.

Travel back and forth across the Atlantic Ocean would not resurge with the same intensity and enthusiasm until the advent of airflight.