The golden strategy of stacked “marginal gains”

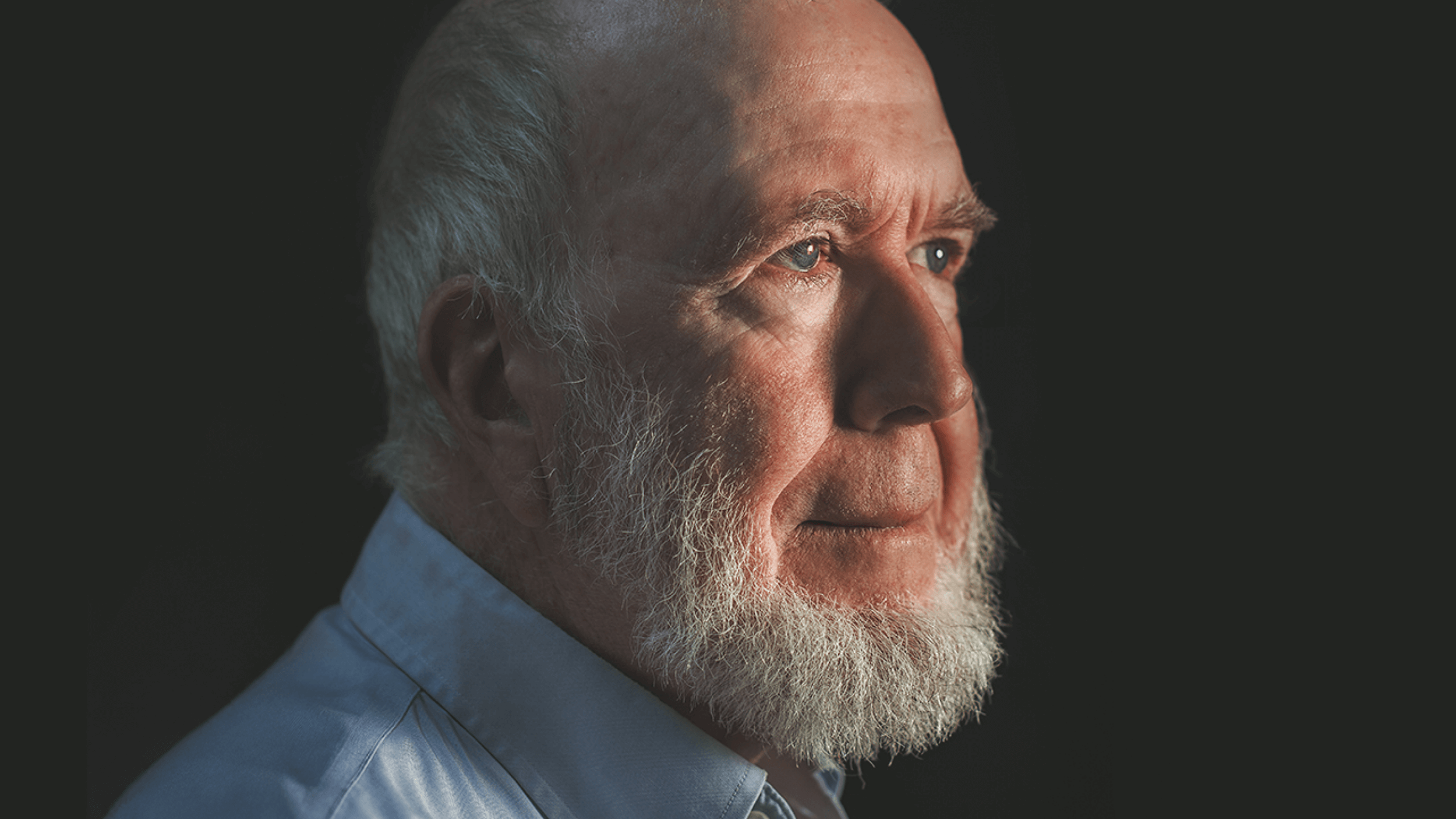

- Legendary British sports coach, Sir Dave Brailsford, followed a winning strategy he called “the aggregation of marginal gains.”

- Brailsford’s plan — applicable to sports, business and investing — holds that incremental changes create significant outcomes over long periods of time.

- The best outcomes in business are often the result of countless iterations, each one slightly better than the last.

In 2008, the British cycling team surprised the world and dominated their rivals at the Beijing Olympics: 14 medals in total. Eight gold. How did they achieve such a remarkable feat? It wasn’t groundbreaking technology. Nor was it an intense new training regimen. It was something much simpler: the aggregation of marginal gains.

In the years leading up to the competition, Sir Dave Brailsford, the team’s coach, calculated that to be competitive, he simply needed to string together multiple 1% improvements across every element of his player’s gear, their stamina, and physical strength. So the team redesigned bike seats. They tweaked wheel designs. They tinkered with the bike frames, swapped out skin suits, tried new diets, bulked up their thighs, and made dozens of other minor adjustments.

The operative word here is minor: no singular change was, in itself, significant. However, aggregating all the small changes together — and compounding them over time — produced results. Extraordinary results. Great Britain has the most track cycling medals in Olympic history.

“The whole principle came from the idea that if you broke down everything you could think of that goes into riding a bike and then improve it by one percent,” Brailsford later said, “you will get a significant increase when you put them all together.”

This concept — what Brailsford called “the aggregation of marginal gains” — represents the idea that small, incremental changes accumulate to create significant outcomes over long periods of time. The idea, of course, isn’t limited to sports. It’s a principle that can (and should) be applied to the worlds of business and to investing.

Unfortunately, that’s rarely the case. When organizations and management teams struggle, they tend to shun the idea of making small tweaks. When there’s pressure to perform in the short term, the typical corporate playbook involves making sweeping, grandiose changes: massive layoffs; canceling product lines; a new CEO who brings a complete change in strategy. On the surface, these big changes may feel productive. They may even feel good. But very often, these massive changes turn out to be short-sighted — and lead to equally massive blunders.

Here is the reality: if management teams actually want to play the long game, big changes can often be antithetical to progress.

Here is the reality: if management teams actually want to play the long game, big changes can often be antithetical to progress. Ironic, huh? Small changes may seem superficial — or even tedious — but stringing them together consistently over time can create incredible outcomes. This is the power of compounding.

The fact is, it’s not entirely our fault that we behave the way we do. Biologically speaking, our brains aren’t wired to always optimize for the best long-term decisions. Take, for instance, a 2004 study from researchers at Princeton and Harvard who set out to explore the nascent field of neuroeconomics. Participants in their study — college students — were given two choices: take money now, or get more money later. It’s a simple study, yes. But it had a twist: while students made their decisions, the researchers monitored their brains using fMRI scans. And what they observed, quite literally, were multiple regions of the brain lighting up — in conflict.

“Our emotional brain has a hard time imagining the future, even though our logical brain clearly sees the future consequences of our current actions,” David Laibson, professor of economics at Harvard University, later said. “Our emotional brain wants to max out the credit card, order dessert and smoke a cigarette. Our logical brain knows we should save for retirement, go for a jog and quit smoking.”

In business, it is possible to employ a logical-brain approach that aggregates marginal gains over the long-term. The best products, for instance, are almost never created in one fell swoop. They’re the result of countless iterations, each one slightly better than the last. Think of all the products you use every day, from your smartphone to your car. Each one has likely seen hundreds, if not thousands of minor revisions, even if they are imperceptible to the human eye.

“Our emotional brain wants to max out the credit card, order dessert and smoke a cigarette. Our logical brain knows we should save for retirement, go for a jog and quit smoking.”

David Laibson, professor of economics at Harvard University

Some of the world’s most consequential inventions went through long periods of small improvements. For instance, the telegraph. In popular lore, the telegraph was simply “invented” by Samuel Morse in the 1830s. However, this is only a half-truth. In reality, the concept for a long-distance communication device had been in development since the 1700s. Various inventors laid the groundwork for a type of device using electrical wires. Despite these early efforts, it took several more decades of refinement and innovation before the telegraph was sufficiently reliable and practical for widespread commercial use. In other words: there is a long journey from concept to commercialization.

This speaks to a broader point: innovation or corporate strategy isn’t necessarily about finding the eureka, “a-ha” moment. It’s about the years of tweaking and tinkering that come after an initial idea. This concept applies on the individual level, too, whether you’re an executive or investor charged with building or leading an organization.

Returning to sports, let’s focus on Roger Federer. One of the greatest tennis players of all time, Federer is known for his particular obsession with small improvements to his game. Over the years, Federer would adjust his footwork by a fraction of a second. Or he’d refine his serve technique. Most impressive to me, however, is simply his longevity as a tennis pro: 24 years as a professional in a sport where the average player rarely makes it past 10 years in the sport. And it all came down to his approach to aggregating marginal gains over time.

One of the greatest tennis players of all time, [Roger] Federer is known for his particular obsession with small improvements to his game.

For instance, in 2014, Federer was at the height of his fame — but in a mid-career slump. He was still in the top 10 rankings, but he hadn’t won a Grand Slam tournament since 2012, and, at 33 years old, media outlets were already lamenting his inevitable demise. “Federer is not going to become a better player now than he once was,” one sports writer remarked in 2014. “He might not be able to halt the decline at all.”

But Federer would not quit. He made subtle tweaks, like switching rackets from a 90-square-inch frame to a 97-inch prototype. This small tweak enabled him to hit harder topspin backhands. He focused on footwork. He watched tape. And then, by 2017, a funny thing happened: he won 2 Major Grand Slam tournaments at the ripe old age of 36. By 2018, he was ranked the No.1 player (ATP) in the world.

Businesses can learn from Federer by focusing on his consistency and his doggedness. It’s not just about making big moves, but about doing the small changes — marginal improvements — day in, and day out. This discipline is what leads to sustained success and compounding over time. The aggregation of marginal gains, when applied correctly, can transform a company’s fortune — and ensure its success for decades to come.

So, slow down, focus on the details, and play the long game. The compounding effect will take care of the rest.