How to succeed and find meaning in a “post-career” world

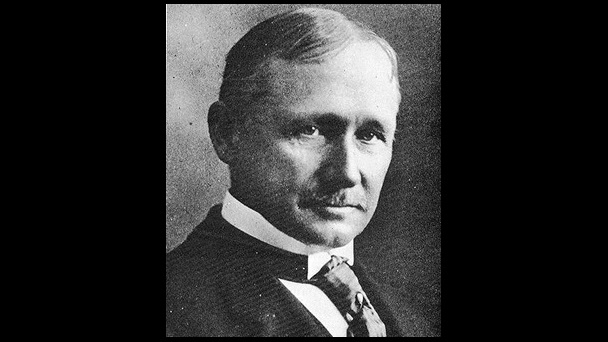

- According to bestselling author Bruce Feiler, we are living through the fourth biggest change in the history of work.

- For a growing number of people, work is no longer about the numbers; it’s about finding meaning in their story.

- To help discover what you want out of work and life, perform a “meaning audit.”

A struggling actor turned on-set intimacy coordinator. A CEO who quit to fight climate change as a consultant and politician. An Army sergeant who became a painter, an accountant who became a small-business owner, and a theoretical physicist who became an aloof ninja in a comedic rock band. (Yes, really.)

Bruce Feiler interviewed these and scores more Americans for his Work Story project. They came from all walks of life, and their paths took them in even more distinctive directions. Yet taken together, their stories revealed something enlightening to Feiler: We are living through a once-in-a-generation redefining of work. Not because of AI or remote work or the post-COVID economy — well, not just because of those. At the core of this cultural shift is a “rethinking [of] the rules of success” and a “rebalancing [of] power away from employers to employees.”

I recently spoke* with Feiler about his new book, The Search: Finding Meaningful Work in a Post-Career World. During our chat, we discussed why the linear career is dead, how viewing work as a math problem fails us, and what we can do to bring more meaning into our jobs and lives.

Kevin: Your book is about how we are redefining work and what that means for us. Why tackle this big idea, and what do you make of the news that the momentum of the Great Resignation is swinging back toward employers?

Feiler: I would challenge that narrative, but let’s start with the bigger question first. I think we are in the midst of the fourth biggest change in the history of work.

For most of human history, it was work version 1.0. Most people grew their own food, made their own candles, educated their own kids, and took care of their own sick.

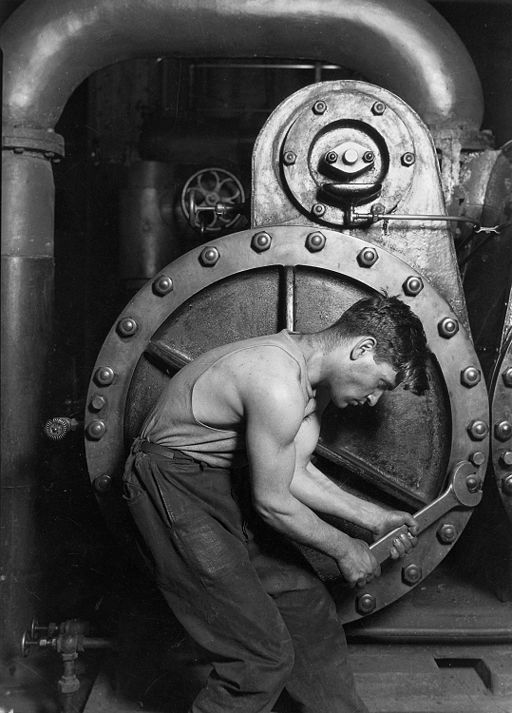

Then came the second big change with the Industrial Revolution. People moved from rural areas to urban ones and had to rethink their entire relationship with work. For the first time, people went to a workplace, thought of themselves as having a job, and made decisions about what they would do in their lives.

The third biggest change occurred in the second half of the 20th century when we went from an industrial-based economy to a knowledge-based one.

Today, we have the fourth biggest change, and there are several reasons for it. We live in a much more global world, so change comes from all parts of the planet — whether it’s trade or a pandemic or whatever. There’s also digital technology, from smartphones to generative AI. But maybe the most important is the demographic change. For the first time, it’s essentially 50-50 male-female, and 50% of workers are under the age of 40.

The combination of all these things has led to a world where workers are no longer bound by pre-existing narratives. You aren’t expected to pick a career at 21, do it for the rest of your life, and jump when the job says jump. Those days are over.

And so, the story about the Great Resignation is false. The number of workers who quit has gone up every year except one this century. We still have twice as many people quitting today as 10 years ago.

Yes, employers are trying to reclaim the narrative. Google says that if people aren’t in the office a few days a week, it’s going to affect their performance reviews. Facebook claims to be putting its foot down by requiring people to show up three days a week. Notice that nobody is saying five days a week anymore. That’s out the window.

Kevin: So, the headlines make it seem like it’s a battle between office versus remote work, employers versus employees. But in reality, it’s bargaining?

Feiler: Let me give you a statistic from my book. The first question I asked in every interview was, What are the upsides about work you learned from your parents? Two-thirds said the value of hard work. As a reporter, I thought, if everybody is giving the same answer, then I’m asking the wrong question.

So, I started asking, What are the downsides of work you learned from your parents? Then things got interesting. Now, people are saying overwork, unhappiness, the strain on family. Okay, that’s the story there. People want to work hard, but they are no longer prepared to suffer like that. There’s a tension.

Let me pick up on what you said about the battle between employers and employees. All of the changes in that relationship began with employees. Employers were perfectly happy in the 1850s to hire people, work them seven days a week, pay low wages, have no safety standards, hire children — all of those things. The whole idea of management science then was how many times can you bend over? How many times can you place a widget in an hour? They would study the hell out of it.

We’re not prepared to sell our souls to the company anymore.

Every change from that status quo — from seven days to six days, from six to five, from every week to vacation time — came about in a short period of several decades because employees pushed back. That’s what’s happening now.

When a third of the workforce quits every year, there’s no penalty on you for changing jobs or professions. It’s less stigmatizing when 80% of women work outside of the home, and 80% of fathers are much more involved in parenting. When both are working and caring about the family, it means we’re not prepared to sell our souls to the company anymore.

End of the coherent career

Kevin: In your book, you reference three lies and one truth about work. I think the first lie is particularly eye-catching and counterintuitive: “You have a career.”

How are we defining career in this sense, and why is that no longer true for today’s workers?

Feiler: A career is a remarkably recent invention, coined about a century ago. It’s a coherent path that characterizes a person’s work life based on their choice of occupation and employer (or string of employers). It’s something that is perceived to have a beginning, a middle, and an end — starting at, say, 20 and ending at 60. If you’re a writer, you may start writing at a newspaper before working at a magazine and then writing a book. But you stick to a certain path with minimal changes.

Today, a person will go through 20 “workquakes” throughout their lives.

And sure, some people say they want to be a surgeon or play for the Yankees, and they do it. But that is not a way to describe what many people do anymore.

Today, a person will go through 20 “workquakes” — moments of instability when you are forced or choose to rethink and reimagine what you do — throughout their lives. That’s one every 2.85 years, and that’s just the average. [Generation] X-ers will go through more [workquakes] than boomers, and millennials more than X-ers. The idea of coherency is no longer the most important thing.

Then there’s digital technology. The iPhone was released in 2007, and it’s been 16 years of rapid change that have created a whole new set of jobs. On top of that, we have AI looking to do it all over again. So the very idea that your 12-year-old or my 18-year-old can be expected to choose the work they want to do 25 years from now is laughable.

Kevin: I still ask my 12-year-old what he wants to be when he grows up in a knee-jerk way. But then I catch myself, and I agree that it’s an absolutely ridiculous question.

Feiler: Exactly. The better questions are those I discuss in my book. What classes excite you? What activities make you happy? Are you motivated to travel, live in a nice house, give back to the community, fight climate change? I think every conversation about work is really a conversation about values.

Quaking in our work boots

Kevin: How can the concept of workquakes help us better navigate work today?

Feiler: A workquake is a jolt. Some are involuntary: You’re in the newspaper business when suddenly everything goes online. But some are voluntary. You might walk away from a job because you want to start a business or you’re tired of commuting two hours a day or you’re a CEO who wants to give back.

So, the term accommodates events that initially may appear unpleasant or pleasant, be involuntary or voluntary. It also allows how you feel about the disruption to evolve over time — which it almost assuredly will.

Kevin: That reminds me of one of my favorite moments in your book. It’s the formula: “Work = Numbers + Words.”

Feiler: Let me ask you a question: What’s the first word that you think of when I say, work?

Kevin: At the moment? Tiring.

Feiler: Right, so you didn’t mention salary, benefits, work hours, or commute time even though that’s mostly how we talk about work. It’s math. Instead, you talked about how you feel right now. That happens to be negative at the moment, and that’s fine (most people have some mix of negative and positive).

The point is: When you ask people about work, it’s how they feel about it, and we don’t do that enough. Too much math, not enough literature.

Kevin: That has an almost cognitive behavioral therapy approach to it. It’s not the situation — or numbers — that make us feel the way we do. It’s the stories we tell about them that influence us the most.

Feiler: That gets to the philosophy, which is that we’ve left this essential part of our lives too much to the economists, who are looking at it through the prism of numbers.

If you look at the news, we are 18 months into a narrative that we will have a recession in the next six months. We’ve gone through that cycle three times, and only now are people admitting that they don’t fully understand the post-pandemic economy. We’re spending so much time talking about interest rates as an instrument to cool down the economy, but it hasn’t changed the labor force. People are still quitting. It’s trickled down a bit, but as I said earlier, it’s still twice as high as it was 10 years ago.

Fewer people are searching merely for work. Most people are searching for work with meaning.

What we’re missing is philosophy. We’re missing the meaning. That’s the fundamental change. People are asking, “How do I feel about work? What meaning do I want from my labor? What sacrifices am I prepared to make and not make?”

Fewer people are searching merely for work. Most people are searching for work with meaning, but we are failing to recognize what’s really going on.

The “meaning audit”

Kevin: In the book, you note that following your passions is bad advice. Since this is also a bugbear of mine, I have to ask: What’s the difference between following your passion and finding your meaning?

Feiler: I grew up watching Johnny Carson on The Tonight Show, and for 30 years, he would always walk out from behind a curtain and stand in one place. How did he know where to stand? There was a star on the ground.

When you tell someone to follow their passion, it not only implies but clearly states that they have a passion. It’s their star on the floor, the pathway of their life. If they can only get on that star, all good things will follow.

But your passion is not a star; it’s a Milky Way. That difference is what we fail to understand. The advice should be to follow your passions while acknowledging that your passions will change over time.

When I ask people this question, only about 10% of people say they followed their passion. Everybody else says something else. They either discovered their passion later in life or made their own passion after realizing they weren’t the same person they once were.

This feeds into a concept in my book called the “meaning audit.” It is based on the premise that multiple times in your life, you’re going to have to do a kind of stress test. You’ll need to ask, “What is it that brings me meaning now? What are my passions at this moment?”

Kevin: How can Big Think readers start the meaning audit process? What can they do to begin uncovering their values and what they are searching for?

Feiler: First of all, we have to understand the difference between happiness and meaning. Happiness is an emotion that’s present and fleeting. The problem with happiness is that you can’t always be happy. Sometimes, your roof gets taken off in a tornado. Sometimes you get cancer at 43 years old. Sometimes, you’re a journalist and journalism disappears.

That’s where meaning comes in. At its core, meaning stitches together the past, present, and future to stabilize and reorient ourselves. It’s what we use to find well-being in moments of unhappiness.

The essence of a meaning audit is to help people stitch their meaning together. It’s a series of questions to ask yourself to try to figure out what you want to do now — not six months ago but today — and then look forward. The simplest way to think about it is to pick three questions: one from the past, one from the present, and one from the future.

So, let’s just take one question from the past: Who was your role model as a child, and what did you admire about them? Now, what matters isn’t who they are; it’s what you value about them. What are the values you’ll learn from your role models as a child?

Now, let’s go to the present. A great question for the present is, “I’m in a moment in my life when ____.” Then fill in the blank. I’m in a moment in my life when I need to make money to pay off student loans. I need to prepare my two children for college. I spent the last five years caring for an aging relative and want to do something for myself now. I need more self-expression. I want to give back. I want to run for office. Whatever it might be.

Finally, I think my favorite question for the future is, “The best advice I have for myself right now is ____.” Ask yourself: What’s the best advice?

Resist the climbing

Kevin: Are there any closing ideas you’d like to wrap with?

Feiler: Work is not exclusively about salary or benefits or hours. It’s not just productivity, profit, and loss. It’s also about meaning. It’s about purpose, identity, exhaustion, renewal, and happiness.

The only way to write a successful story is to resist the climbing. The primary way we’ve talked about work is about climbing: a higher floor, bigger office, greater benefits, more salary. But the people who are happiest and most successful don’t just climb. They also dig. It’s an act of personal archeology to figure out the story you’ve been trying to tell your whole life. The hardest part is giving yourself permission to tell that story even if it disappoints somebody else.

Your work is a story. Each of us has to construct that truth, so run toward the words, embrace the literature. Write your own story.

Kevin: Where can people find you online if they want to learn more?

Feiler: You can find me at brucefeiler.com and on all social media (Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram). I also write a newsletter, “The Non-Linear Life,” which is at brucefeiler.substack.com.

* Note: This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.